In his classic book The Self-Made Man in America (1954), the University of Wisconsin historian Irvin G. Wyllie declared that “no questions have been more central and none have been answered more confidently” by Americans in their history than “What makes a man?” The collective American response for some 250 years has been that meritocracy—the “myth of rags to riches”—is a real thing. “The legendary hero of America is the self-made man,” Wyllie declared. From Benjamin Franklin to P.T. Barnum, the self-made man “represents our most cherished conceptions of success”—this last word the “principle American aspiration” expressed “in a single word.”

The influence of the Scofield Reference Bible on American evangelical and fundamentalist Christianity is incalculable. And the man who brought it into being was as American as, well, the myth of the self-made man.

The tale of the self-made man is most often told about pioneering titans of industry, but it is no less alluring in the world of religion. This is because the trope doesn’t just make for a compelling biography. It does significant intellectual work. Wyllie called it the “cult of the self-made man” derisively, but we might simply observe that any such concept comes embedded with assumptions and emphases. The “self-made man” tends to privilege inner over external realities, character over circumstance, will over whim, purpose over contingency, cultivation over inheritance. The story of the self-made man thus diminishes the role of history and historical forces in the man’s accomplishments. The self-made man creates a unique way of seeing the world. “The law of success is in the person himself,” Henry Ford said, explaining the same concept. “What is the law by which the apple becomes the apple? Well, it’s the same way with success.”

Cyrus Ingerson Scofield, born in 1843, ascended, by the end of his life, in 1921, to the short list of the most influential religious writers in American history. He was, by any measure including his own, a self-made man. Born in rural Michigan and spending much of his later career in St. Louis, Massachusetts, and Dallas, he embodied the rags-to-riches arc. Scofield is thus interesting on this basis alone, as a figure who did what Wyllie and many others have confirmed is the exception rather than the rule of American history. As is the case with many such self-made men, Scofield’s life is contentiously debated. Some of his key details and decisions have factual disparities, not to mention contested judgments about motives.

Really, though, Scofield’s biography is a proxy battleground for debating his most significant contribution to American religious culture: the Scofield Reference Bible. In addition to a 40-year career as a minister, speaker, and popular writer, he published the Bible that bears his name in 1909 to widespread fanfare. It sold in the millions within a decade and has gone on to become Oxford University Press’s best-selling book ever. Since then, the “Scofield Bible” has been the spiritual keepsake for millions of American evangelicals and fundamentalists, and remains in print in dozens of languages. It was the greatest popularizer of the theology of dispensationalism, promoting a literal or plain reading of Scripture with attendant beliefs in an imminent rapture and a distinct prophetic future for the nation of Israel. The Scofield Bible’s continuing relevance is evident in the critical attention it continues to attract on these and other themes in media, ranging from academic studies of fundamentalism to the punditry of country musician John Rich on the Tucker Carlson Show.

Like the man Scofield, the Scofield Bible has its own fascinating connection to the “myth of rags to riches.” It is the theologically conservative study Bible that sold better than all the others in an age of biblical higher criticism and surging Protestant modernism. It is the independently funded passion project, undertaken outside the strictures of any formal academic institution by a writer with no formal theological education, that was courted by Oxford University Press. While not absolutely unprecedented (the Geneva Bible of 1560 included a running commentary with a Puritan/Calvinist emphasis), its success nonetheless created one of the largest bookselling markets of the 20th century: the personal study Bible, which has gone on to be imitated but never surpassed by a steady stream of later attempts.

Just as importantly, the references and notes in Scofield’s Bible bear the mark of the self-made-man trope. Scofield presents his interpretations as commonsensical and straightforward; he is masterful at assimilating disparate theological commitments, some rather novel to his time, and presenting them in an unassuming and uncontroversial idiom. Like a self-help book that emphasizes the quality of character above all else, the reference Bible claims to be derived from, rather than applying itself to, a simple commitment to “rightly dividing the word of truth.” And like the self-made man concept, the Scofield Reference Bible refuses to acknowledge specific historical debts or influences outside those of the titular Scofield, whose own character and quality thus become decisive for establishing the Bible’s credibility.

If not exactly a Horatio Alger story, Scofield’s life trajectory was nevertheless one from obscurity to prominence, from marginal to central influence over a swath of American Protestantism. It is no small fact that, in his own portrayal of his life, he adhered closely to the “origin myth” of the American self-made man that features rural, self-driven boys who make the best of their circumstances usually, in Wyllie’s summary analysis, with the help of women. In his own telling, Scofield’s childhood was spent in a “frontier house” in Lenawee County, Michigan, where he was a gifted reader from a young age (the unsubtle scene of the boy studying the career of Alexander the Great is on page two of his authorized biography). Though his mother died giving birth to her son, Scofield recalled frequently the family lore that she uttered a prayer over her newborn that he would serve God in his life.

These facts of Scofield’s early life would remain undisputed, but virtually everything after he turned 17 has at least two versions: his and his opponents’. As his collaboration with biographer Charles Gallaudet Trumbull the year before his death indicates, Scofield was keen to shape public understandings of his life. He drew examples from it frequently in his writing and sermons. At the same time, as he developed a national profile he faced an increasingly embittered opposition to his ideas and influence. The facts and interpretations of nearly every phase of his career have been cast by critics as calculating and dishonest, the very inverse of the “self-made” virtues of integrity, frugality, and prudence.

As a case in point, by the time the Civil War erupted, in April 1861, Scofield had moved to Tennessee to live with his sister. In a strange turn, the 17-year-old lifelong Michigander lied about his age to join the 7th Regiment of the Tennessee Infantry of the Confederate Army. Just a year into the conflict, Scofield had seen battle multiple times. He served at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862 but was soon discharged by request for being underage when he enlisted, in poor health, and not a resident of the Confederacy. Was he a hero or a traitor? There were two sides to the story for the rest of his life.

After the war he found his way to St. Louis and joined the elite social circles of another sister who had married into one of the leading French families of the city. Scofield’s official biographer dutifully mentions that though Scofield, who decided he wanted to become a lawyer, had access to wealth to fund his education, he rather “believed it was best for him to work things out for himself and provide for his own education and support. He wanted to fight his own way; and he did so.” The “self-made” boy was becoming a man. His opponents perceived a cloying self-promoter who used family connections and a move across state lines to become, at the age of 29, the attorney general of Kansas. Was Scofield a diligent rising star or a bootlicker? There were two sides to this story, too.

Scofield was still a hard-drinking lawyer in 1879 when a colleague shared the gospel with him.

Scofield and his opponents agree that in his 30s he was an alcoholic. It was one of the factors that contributed to his resigning the same year he was appointed attorney general. There was also a cloud of financial scandal that dogged him all the way back to St. Louis. By the mid-1870s, Scofield had abandoned his wife, Leontine LeBeau Cerrè, and two daughters (he would divorce in 1883 and remarry the next year). The extent of Scofield’s corruption both at home and in his career would be fodder for speculation and topics of pointed vagueness by Scofield for the rest of his life.

Vagueness, but not silence. Scofield was still a hard-drinking lawyer in 1879 when a colleague shared the gospel with him. As his official biographer narrated the conversion, “The two men dropped down on their knees together. Scofield told the Lord Jesus Christ that he believed on Him as his personal Saviour, and before he arose from his knees he had been born again: there was a new creation, old things had passed away, behold, all things had become new.” Scofield claimed that in that instant he was also cured of his alcoholism. He wrote to Trumbull that, after finishing his conversion prayer, “instantly the chains were broken never to be forged again—the passion for drink was taken away. Put it ‘Instantly,’ dear Trumbull. Make it plain. Don’t say: ‘He strove with his drink-sin and came off victor.’ He did nothing of the kind. Divine power did it, wholly of grace.”

In the 1880s, Scofield mentored under one of the leading early expositors of “rightly dividing the word of truth,” Presbyterian pastor James L. Brookes of St. Louis. From there he entered into the orbit of the most important revivalist of the era, Dwight L. Moody, eventually producing a popular correspondence course for Moody Bible Institute and becoming pastor in Dallas and then, in 1895, of Moody’s hometown church in Northfield, Massachusetts. Along the way he became ordained as a Congregationalist minister and began to refer to himself as “C. I. Scofield, D.D.”—a credential he never adequately sourced and another point of biographical contention.

Among his regular venues for national speaking were prophecy conferences, where he expounded the dispensational view of an imminent rapture to heaven of the saved and a looming Antichrist let loose on earth, as well as “Victorious Life” holiness, teaching that the Holy Spirit could empower Christians to do great things both personally and in Christian service. Scofield frequently used his own cure from alcoholism as the example. “The secret of Dr. Scofield’s ‘Victorious Life,’” wrote Trumbull, “is the same and only secret of the Victorious Life of every believer wherever such victory is experienced: he ‘let go, and let God’; he did not try to add his efforts to God’s finished and perfect work.”

Scofield’s interpretation of his own life aligned with his interpretation of the Bible. Both were about humankind’s calling to submit to God, who, working through the consenting human vessel, would use the power of the Holy Spirit to accomplish superhuman acts for the sake of God’s glory. In 1902, when he took what turned out to be a permanent leave of absence from pastoring to work on his reference Bible, Scofield was developing a set of notes for his Bible that aligned with his experience, which, in the hermeneutical circle he had used throughout his career, created empirical validation of his interpretations.

The phrase “rightly dividing the word of truth” is associated with Scofield’s earliest days as a writer. He published a popular pamphlet under that title in 1888 which laid out “something of the ordered beauty and symmetry” of the Bible from which right belief and practice flowed. The phrase comes from a passage where Paul enjoins Timothy to “study to show thyself approved unto God, a workman that needeth not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth” (2 Tim. 2:15).

Among Scofield's regular venues for national speaking were prophecy conferences, where he expounded the dispensational view of an imminent rapture to heaven of the saved.

The influences that Scofield brought to bear on the reference Bible were obscured by his own commitment to a “self-made” presentation. The tagline of “rightly dividing” is a case in point. Though a familiar phrase because of its sourcing in the Bible, Scofield invoked it with a particular meaning that was indebted to the emerging theology of dispensationalism, which divided the biblical story into discrete eras (dispensations) that numbered many more than the two that most Christians saw in the division of their Bibles into Old and New Testaments. The term dispensation is an English translation of the Greek oikonomia, a combination of oikos (household) and nemein (management) that is found four times in the King James Bible. Scofield eventually landed on the number of seven, while others in the dispensationalist camp would count between five and eight. Nearly all proposals began with the dispensation of Edenic innocence, followed by a succession of law-based dispensations, before coming to the present age of grace, sometimes called the “church age,” to be concluded with the millennial kingdom in the future.

The specifics were less important than the implications. A dispensation is a discrete era of God’s dealing with humanity and entailed interpreting biblical passages based on what dispensation they were written in or intended for. Scofield himself, in one of the more infamous consequences of his application of dispensational time on the biblical text, taught that the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5–7) was intended not for Christians today but for Jesus’ immediate audience of Jews and described the ethics of the future Jewish millennial kingdom. Other variations of dispensationalism, especially so-called hyper-dispensationalism, interpreted the beginning of the church age in the middle or the end of the Book of Acts (instead of in Acts 2 and the day of Pentecost) with the implication that baptism and/or the Lord’s Supper/Holy Communion—the two cardinal ordinances/sacraments of most Christian traditions—were not to be practiced by Christians today.

These implications of Scofield’s approach may sound extreme (and he vehemently rejected hyper-dispensationalism), but Scofield’s skill was to naturalize and accommodate the connotations of his notes to the conservative Protestant culture of the early 20th century. The preface to the Scofield Reference Bible did just this. He listed 11 advancements or innovations that justified the Bible’s existence, ranging from the need for a modernized concordance system to new understandings of prophetic literature (largely by fellow dispensationalist writers). This gesture to innovation was framed as both recent (informed by “the last fifty years” of scholarship) and timeless (“Expository novelties, and merely personal views and interpretations, have been rejected”).

In all this, Scofield acknowledged no particular theological or ideological allegiance. He simply asserted the existence of dispensations and accompanied it with a misleading quote from Augustine (which would be removed in later editions). He cited numerous networks of scholars or pastors who were consulted, but they were referenced abstractly as “learned and spiritual men, in every division of the church and in every land.” It is the scholarship produced by these nondescript experts that is the “self-made” core of the reference Bible, the quality of which Scofield is essentially attesting to for the lay reader. “The Editor,” he wrote in the third person, “has proposed to himself the modest if laborious task of summarizing, arranging, and condensing this mass of material”—a process he wanted to portray not as original or as we would say today “edgy,” but as simply required based on the merits of the scholarship and the needs of readers.

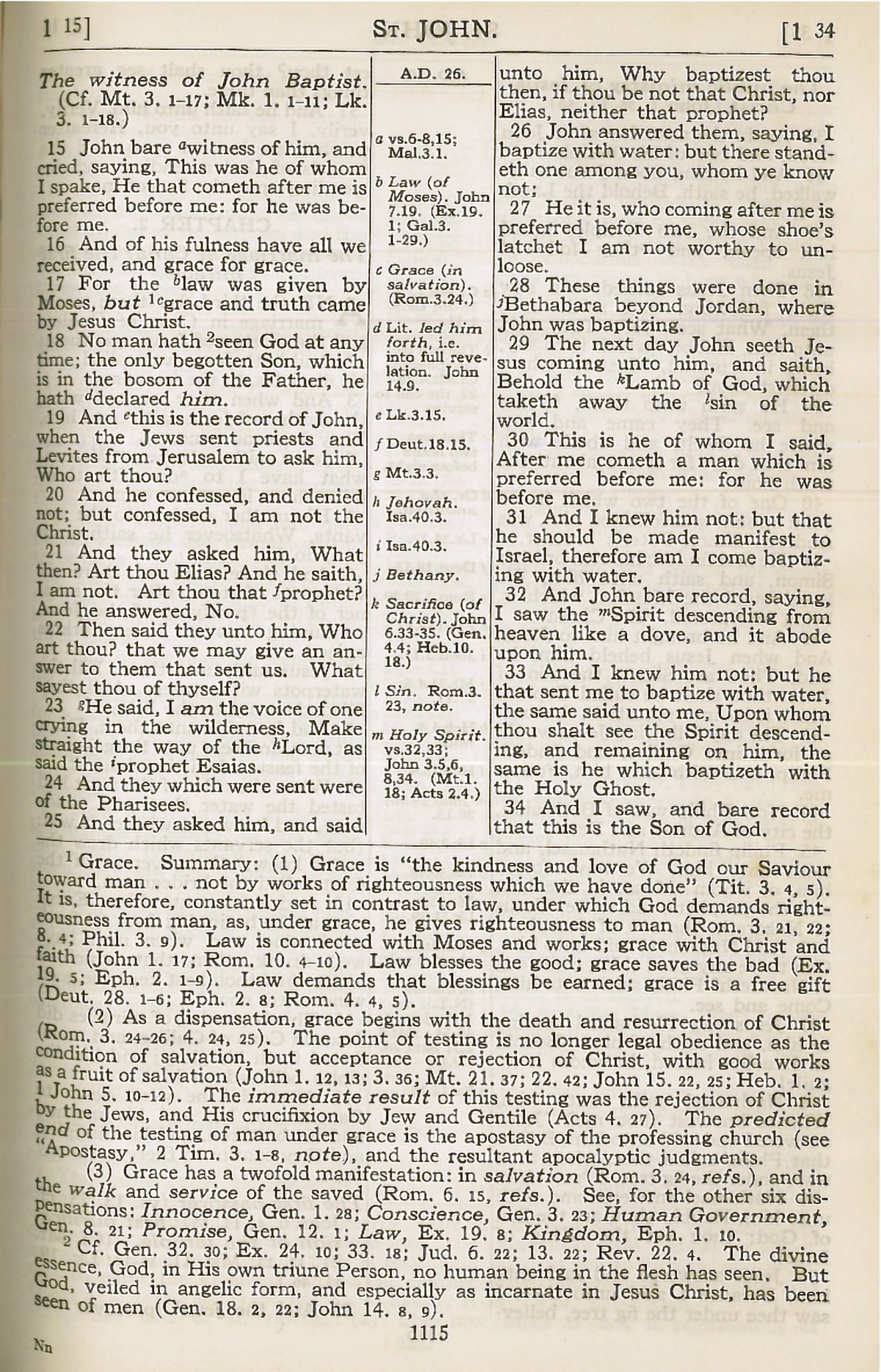

The reference Bible itself was made up of the King James text with multiple “helps” on each page to assist the common reader in gaining insights from the hitherto inaccessible “vast literature” that Scofield consulted. The main feature was the footnotes and annotations at the bottom of each page helping to explain the text and keywords and to situate major events in dispensational time. But the notes were just one part of the presentation. As historian Donald Akenson has claimed, with a touch of exaggeration, the entire presentation was “so thorough and so visually unique that it was a new Bible” and led its devout readers like God led the Israelites, by “a guiding cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night.”

The Scofield Reference Bible advanced two fronts of modern study Bibles, the first being “visual” or formatting innovations that are now mainstays of all evangelical study Bibles. Scofield’s became the first mass-produced Bible to include a comprehensive chain-reference system and concordance to link words, allusions, and stories across the entire biblical text. The references ran down the middle of the page, dividing the two columns, and extended down to where the footnotes began. In passages—especially Genesis, the Gospels, and Revelation—these footnotes regularly took up more than half a page and offered far more words of explanation than the Bible itself offered. As important as the references and notes, Scofield also added thousands of subject headers in the text itself to describe a section’s topic or theme. Italicized and centered in the column between verses, these headers introduced such concepts as the beginnings of new dispensations, key theological terms, and interpretations of the actual biblical content to follow.

For Scofield, Israel was an entirely Jewish entity, one that remained distinct from 'the church.'

The Scofield Reference Bible used this format to advance Scofield’s particular exegesis. In adhering to the developing dispensational theology that he inherited from his mentor, James Brookes, and others, Scofield embedded a complete and permanent distinction between “Israel” and “the Church,” God’s two chosen peoples. For Scofield, Israel was an entirely Jewish entity, one that remained distinct from “the Church.” While most other Christian traditions saw a continuity (or supersession) from Israel to the Church, Scofield regarded these as unique, with separate final destinies for Israel as the kingdom of God on earth, the Church in communion with God in heaven. One major purpose of “rightly dividing the word” was to discern whether a passage of Scripture was principally about Israel or the Church.

The consequences for this “Church-Israel distinction” became especially apparent in the large prophetic passages of the Old Testament, which spanned the major prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel) and the dozen minor prophets. These prophecies all took place, according to Scofield, in the fourth dispensation that began in Genesis 12 with the introduction of Abraham. While up to this point the Bible was concerned with “the whole Adamic race,” the introduction of Abraham signifies a major shift. “Henceforth, in the Scripture record, humanity must be thought of as a vast stream from which God, in the call of Abram and the creation of the nation of Israel, has but drawn off a slender rill, through which He may at last purify the great river itself.” Consequently, Old Testament prophecies “have primarily in view Israel, the little rill, not the great Gentile river.” Every promise of national restoration God makes to Israel, every vision of millennial bliss (“swords into ploughshares”), every expression of covenantal love was intended solely and forever for the “little rill.” It was a category error, in Scofield’s view, to apply any of this to the Church or the “great river” of humanity.

This commitment is what is usually meant by Scofield’s and later dispensationalists’ “literal” or “plain” reading of prophetic literature. Rather than allegorical or spiritual meanings, Scofield preferred to interpret the Old Testament text without reference to the New Testament development of the Church. Readers needed to “exclude the notion—a legacy in Protestant thought from post-apostolic and Roman Catholic theology—that the Church is the true Israel.” The implications of this commitment were striking. For example, land promises that God gives to Israel or that are prophesied about Israel are to be interpreted geographically and eternally. While prophecy passages were highly symbolic to all interpreters, dispensationalists regarded these symbols as depicting real-world events that would happen in the sequence represented in the prophecy. Moreover, while many Christians interpreted Old Testament prophecy passages to have been fulfilled (in this same literal way) in the past, either after the Babylonian exile or in the Second Temple era, Scofield understood most prophecies as having remained unfulfilled and therefore prophesying still-future events.

In theological terms, Scofield advanced a futurist interpretation of biblical prophecy that was premillennial (anticipating the Second Coming before the millennium—the 1,000-year reign of Christ on earth after a time of “tribulation”) and dispensational (“rightly dividing” the Bible). He used these words sparingly, however, and instead offered more digestible descriptions of the “dispensations” and definitions of Israel and the Church. If this was indeed the right way to divide the Bible, then the interpretive consequences were simply the virtuous fruit of the virtuous tree. Things that are associated with dispensationalism today, including the rapture (the “taking up” into heaven of the church), the figure of the Antichrist, and the “Mark of the Beast” (as cited in the Book of Revelation), are regarded by Scofield and his successors as simple downstream consequences of the right approach to the Bible.

Wyllie declared in his study of the “self-made man” that the central question of American culture was “What makes a man?” We might ask as a follow-up to the story of the self-made Scofield, “What makes a Bible?”

A common refrain among dispensationalists today is that the historical precedents in church history for their readings of Scripture are less important than whether what dispensationalism teaches is true. Even in a recent effort to establish the historical continuity of Scofield’s and others’ teaching, titled Discovering Dispensationalism, the editors insist that it is “Scripture—and Scripture alone—that acts as the cistern of truth from which dispensational thought has always drawn.” This seems to be one major legacy of the Scofield Reference Bible and the religious subculture it helped bring into being. The demotion of history is also evident in the “self-made man.” In both cases, history and historical influences pale in comparison to the merits, will, and consequences of a person’s, or a book’s, life.

Scofield lived another dozen years after the publication of his reference Bible. In that time, it sold briskly and Scofield was able to issue a major revision in 1917. The new version cleaned up errors and offered even more scaffolding for his notes in the form of an extended introduction that continued to elide any specific intellectual influences, even while developing more particular terms. After introducing a “three-fold” division of humanity into “the Jew, the Gentile, and the Nations,” he warned that these terms meant something different in his reference Bible than in others. “Do not, therefore, assume interpretations to be true because they are familiar.” In an inverse to the typical practice of scholarship, Scofield implied that judging a book on its continuity to the past could be a sign of theological laxity rather than rigor.

In a true “self-made” arc, the Scofield Reference Bible’s threefold definition of humanity and other terms would become the more familiar ones for millions of Americans over the next century, not only through the millions of copies sold of the 1917 revision and the further revised 1967 New Scofield Reference Bible, but via the many similar efforts undertaken by other dispensational commentators. One of the major interpreters of dispensationalism, Charles Ryrie, longtime professor of theology at Dallas Theological Seminary (founded by Scofield’s disciple Lewis Sperry Chafer) and onetime president of Philadelphia School of the Bible (founded by Scofield in 1914), produced his own Ryrie Study Bible in 1978 that has gone on to sell millions. Other examples include the Criswell Study Bible (by W.A. Criswell, first published in 1979), the Spirit-Filled Life Study Bible (by Jack Hayford, first published in 1991), the MacArthur Study Bible (by John MacArthur, first published in 1997), and the Prophecy Study Bible (by John Hagee, first published in 1997). These Bibles have sold in the combined millions, boosting their creators’ profiles on the religious landscape and advancing dispensational ideas at the same time.

Scofield’s innovations introduced in 1909 persist, with only minor revisions, in all these later entries. Nevertheless, the successor study Bibles remain, quite literally, “self-made” in the inattention to historical precedent and the outsourcing of authority to the titled creators’ reputations. The self-titling is another small testament to the “self-made” trope’s grip established in large part through Scofield’s success.

Wyllie concluded his study by observing that, while “impressive statistical data” had shown that the “self-made man” was a rarity in American history, the falsehood of its attainability persisted. He concluded in an unfortunate example of class prejudice that the reason for its continued popularity, despite scholarly myth-busting, was that “men on the bottom need dreams.” We might rather observe along with Wyllie that, while the “self-made man” was and is a statistical exception, his true source and power is embedded far more deeply in a set of assumptions and claims about the world, in the priority of inner over external, and character over method. So, too, is the self-made Scofield Reference Bible. Its resilience in light of a century of skepticism and dismissal by scholars is a humbling testament to the “self-made” trope being an exception but not an impossibility. A “self-made” aphorism commonly attributed to Benjamin Franklin is “energy and persistence conquer all things.” Scofield’s conversion declaration is the biblical cognate that unlocks a deeper sense of how the “self-made” tale has shaped American Christianity: “old things are passed away, behold, all things are become new.”