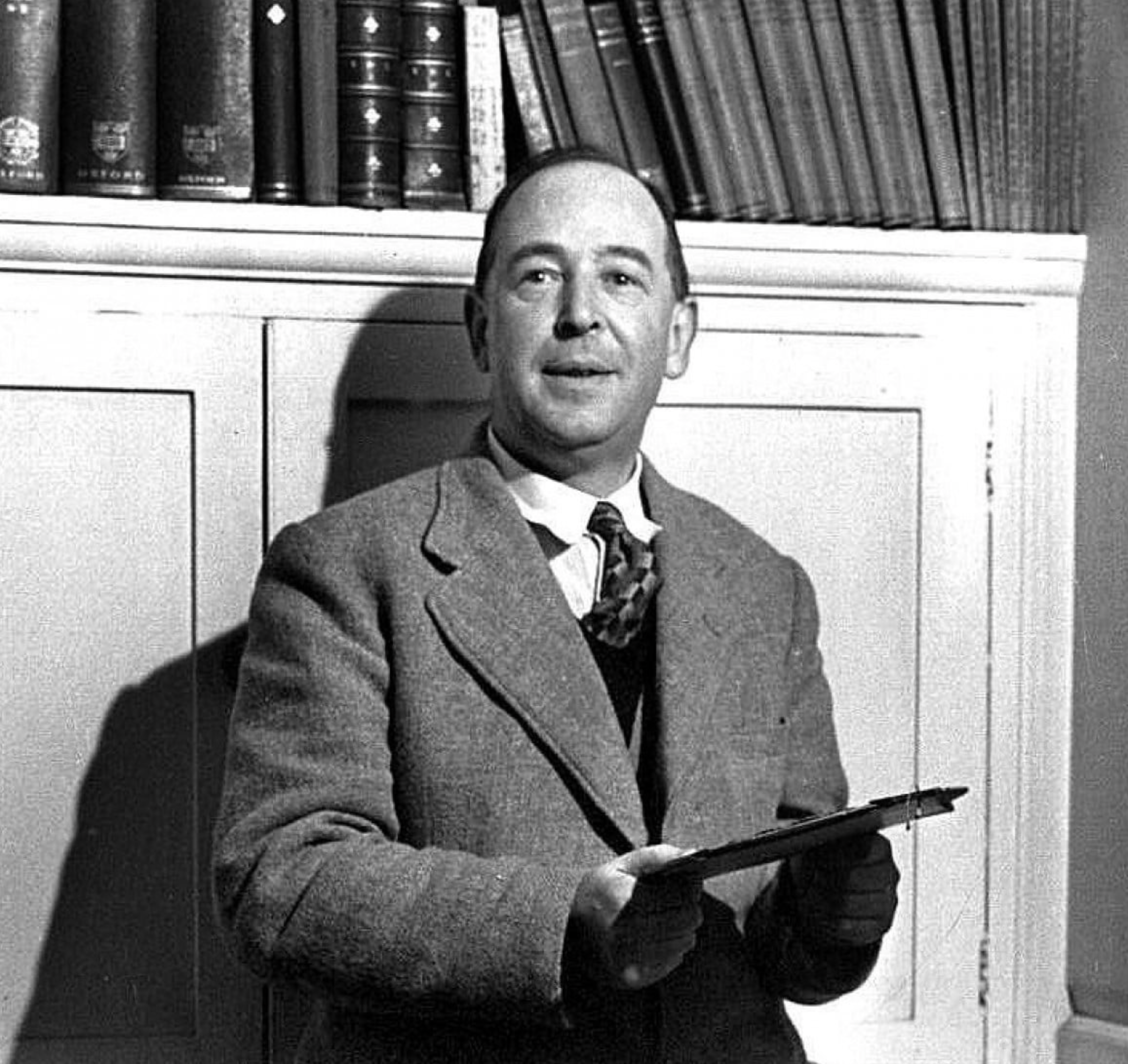

When you pick up Michael Ward’s After Humanity—a 240-page “guide” to a pamphlet which, in my copy, runs to 49 pages—it is hard not to ask yourself what C.S. Lewis himself would have made of it. Fortunately, he told us. In a short essay later republished under the title “On the Reading of Old Books,” Lewis advanced two arguments for reading old books rather than the modern scholars who comment on them. The Abolition of Man has now become an old book itself, and both arguments apply.

Lewis’ first point is that students avoid tackling ancient writers directly for fear they will not understand them, but in fact “the great man, just because of his greatness, is much more intelligible than the modern commentator.” That note of contempt for his scholarly peers is authentic. Part of Lewis’ immense appeal as a writer is that his warmth and humanity is spiked with acid and misanthropic wit. So what would he have made of Ward’s After Humanity? He would have played with it like Aslan playing with a dwarf—but without velveting his paws. Perhaps the greatest compliment we can pay to Ward is to say he would enjoy the treatment.

How good a prophet was C.S. Lewis? Have his worst fears of scientism and anti-human reductionism run amok come true? Or did his hope in the abiding truth of the Tao prove well founded after all?

By Michael Ward

(Word on Fire Academic, 2021)

The Abolition of Man has, indeed, become a minor modern classic. It is a set of three lectures, delivered in 1943, which make a case not for Christianity but for the objective reality of morality. “Natural law” is the term Lewis would instinctively have used for this reality, but here he is straining to make a universal rather than a specifically Christian argument, so he calls it “the Tao.” He defines that as “the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, to the kind of thing the universe is and the kind of things we are.” He does not try to argue for the Tao, since he believes it to be self-evident, a part of the human condition. Instead, he warns against attempts to collapse objective values into relativism, and especially against eugenic or (as we would now say) post-humanist attempts to reinvent our value systems, as a one-way ticket to meaninglessness. The creature left at the end of this process, he warns, is a mere “trousered ape,” a ghastly simulacrum of an irrecoverable humanity.

As Ward points out, this wartime jeremiad has found an appreciative audience, more so than Lewis’ more upbeat works: We are, in this day and age, suckers for doomsaying. The Abolition of Man’s admirers range from Pope Benedict XVI to the ferociously combative atheist philosopher John Gray. Lewis even secured the supreme endorsement of having Ayn Rand scrawl furious ad hominem attacks in the margins of her copy (“The abysmal bastard! The cheap, drivelling non-entity!”). But does this “great man” need a commentator such as Ward to serve as our “guide”?

Much of Ward’s book consists of literal page-by-page commentary, of the kind that Lewis, as a medievalist, would instantly recognize. Some of it is simple glossing: Lewis’ text is dense with literary allusions that many modern readers will miss, although their meaning is usually easy enough to guess. The pitching of some of Ward’s notes is a little weird. His imagined reader apparently does not know what the word propaganda means but is familiar with the distinction between “connaître knowledge” and “savoir knowledge.” Some notes are so po-faced that I want to suspect a spoof. When he tells us solemnly that the pronunciation of Tao “is best approximated by the word Dow, as in the Dow Jones Index,” surely we are being trolled?

Still, I have to admit that Ward passes Lewis’ first test. The commentator may not write as engagingly as the “great man,” but he is entirely intelligible and does illuminate Lewis’ deceptively dense argument. Students will certainly find it useful, not least because he has assembled and quoted extensively from a wide range of shrewd commentators on Lewis’ work.

But Lewis had a second argument for reading “old books,” which is that every era, including one’s own, suffers from some “characteristic blindness” or other. When we read our contemporaries, he warns, we are reading authors liable to the same errors as we ourselves are. The great merit of writers from other ages is that they are prey to different mistakes, so we will instantly recognize theirs and avoid them, while they will directly challenge the assumptions we did not even realize we had made. And Lewis, a lifelong science fiction enthusiast, could not resist adding that books from the future would do the job just as well, if only we could get to them.

Well, now we can. What does this book from Lewis’ future have to say about his characteristic blindnesses, and what would he have to say about its?

Ward is a very gentle critic. His pretence of neutrality toward a book he plainly loves is charming but utterly unconvincing. Still, he does put it instructively into context. Although Lewis explicitly argued—in 1943!—that “the process which, if not checked, will abolish Man goes on apace among Communists and Democrats no less than among Fascists,” every line of The Abolition of Man bears the stamp of war. Indeed, of both wars: Lewis’ own teenage combat experience in 1917–18 underpins it. When, in the first lecture, he effortlessly made willingness to lay down one’s life the measure of any value system’s worth, he knew of what he spoke. His breezy citation of the principle Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori—“It is sweet and fitting to die for the homeland”—clearly makes Ward uncomfortable (he argues, pretty convincingly, that Lewis had probably never read the Wilfred Owen poem that has made that line so notorious). The lectures begin with a broadside against a pair of hapless Australian authors who serve as exemplars of spineless moral vacuity: In private correspondence, Lewis explicitly tied them to the slur blaming the fall of Singapore in 1942 on Australian cowardice.

The more important question, of course, is how Lewis’ dreadful warnings look nearly 80 years on. Like any competent prophet of doom, he was vague enough to avoid potential disproof. He placed the final “abolition of Man,” hypothetically, in the hundredth century AD, while describing it with altogether more urgency than that implies. Ward is ready to find signs of the “abolition” in our own age. The power wielded by transnational corporations is made part of Lewis’ dehumanizing process, a view that perhaps looks less persuasive than a few years ago, now that we have seen how pandemic and war can send corporate titans scurrying back to old-fashioned governments for safety.

My problem here is not with Ward but with Lewis: His notion that human beings have ever been particularly rational is romantic but does not fit the history I know.

More convincingly, Ward takes up Lewis’ lament that we are no longer a rational species, truly capable of persuading each other to accept unwelcome truths by logical argument, and applies it to our own “post-truth” world in which we are all supposedly sealed in our own bubbles of subjectivism. My problem here is not with Ward but with Lewis: His notion that human beings have ever been particularly rational is romantic but does not fit the history I know. Perhaps I am so inured to living in a post-truth world that I am projecting our own age’s flaws onto the past. All I can say is, I don’t think so. When Lewis, through his diabolical alter ego Screwtape, said that, once upon a time, most people were really “prepared to alter their way of life as a result of a chain of reasoning,” he was I think describing an ideal rather than a historical reality. I’d be readier to believe he was right if he could provide some real examples.

The Abolition of Man in fact holds up pretty well 80 years on, but like any old book, some of its characteristic blind spots have become clearer. Not least—and it is an awful thing to say to any prophet of doom—we are forced to concede that its worst fears do not seem to have come true. Ward repeatedly draws illuminating links between The Abolition of Man and Lewis’ weakest, preachiest novel, That Hideous Strength (1945), a nightmare vision of power-hungry, value-free scientism. It was a reasonable extrapolation from the interwar world, in which post-Christian thinkers offered few ethics beyond flimsy and dangerous cod-Darwinist mirages such as “preserving the species.”

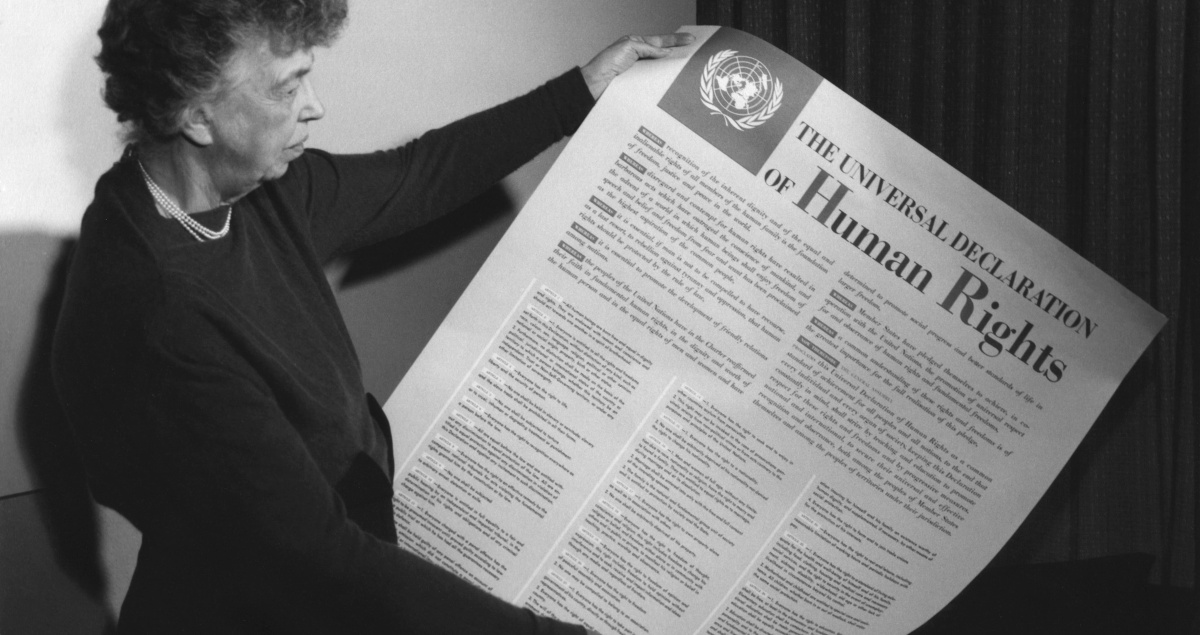

But this is not how the post-1945 world has turned out. It is dominated by a secular value system, humanism, with an ethic of inalienable human rights at its heart. That ethic may be a castle built on air. It is a truism amongst moral philosophers that “human rights” are no more than an act of collective faith. But it is a faith we hold nevertheless. You could happily slot clauses from the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights into Lewis’ multicultural list of “illustrations of the Tao.” Apparently he was more right than he feared: Universal human values are in fact pretty universal, and if suppressed in one form will spring up in another.

The culmination of Lewis’ polemic is his fear that future “Conditioners” will acquire the power to mould human nature in all subsequent generations to their will. This is certainly conceivable, and Lewis’ central warning holds: Humanity will not have such power; rather, a few humans will use it to impose their power on the rest. But humans are ornery creatures, and 80 years of experience suggests our nature is not as easily manipulated as Lewis and his contemporaries feared and hoped. Like it or not, we seem to be stuck with us as we are.

There is another critique of Lewis’ argument that Ward does not want to make, but we need to mention. When Lewis wrote “Man,” Ward assures us, he simply meant “humanity,” but this is the same C.S. Lewis who thought Christianity has “the rough, male taste of reality.” What he in wartime calls the “abolition of Man” sounds awfully like emasculation—or, indeed, deracination. Lewis’ admirable love for the Western tradition had, by the end of his life, curdled into a grouchy conservatism, adept at finding ageless principles in which to clothe his passing prejudices. In The Abolition of Man, the process has already begun. He allows for the possibility of moral development, of new insights—but grudgingly, minimally, in a passage of uncharacteristically flat prose, not enlivened by so much as an example. It is a view from within the citadel, from a man with far more to lose than to gain.

We can (in fact, we must) accept Lewis’ basic moral insight—but, unfashionable as it may seem, we can be more optimistic and more ambitious than he was in 1943. There is plenty of space left for our morals to grow into their full stature while remaining fully within the Tao: a shameful amount of space. And Lewis himself—who, even at his most curmudgeonly, embraced the theological virtue of Hope—admits it. In a curious passage at the end of The Abolition of Man, he imagines how a “regenerate science” might prove part of the solution to the dehumanizing scientism he fears: a science that “when it explained … would not explain away,” which “would not be free with the words only and merely,” and that would submit to Nature as well as conquering her.

I do not say we have such a science, but since the 1940s we have moved that way. There is less crass reductionism, more awareness that complex systems neither can nor should be wholly controlled, and a more ready recognition that we ourselves are part of that whole. Lewis is telling us that those are morally rich insights. It may be that our greatest bulwark against the abolition of man is to recognize that the whole created order exists not for humans to plunder and interrogate it but to treasure it as a gift and a glory of which humanity is one small part.