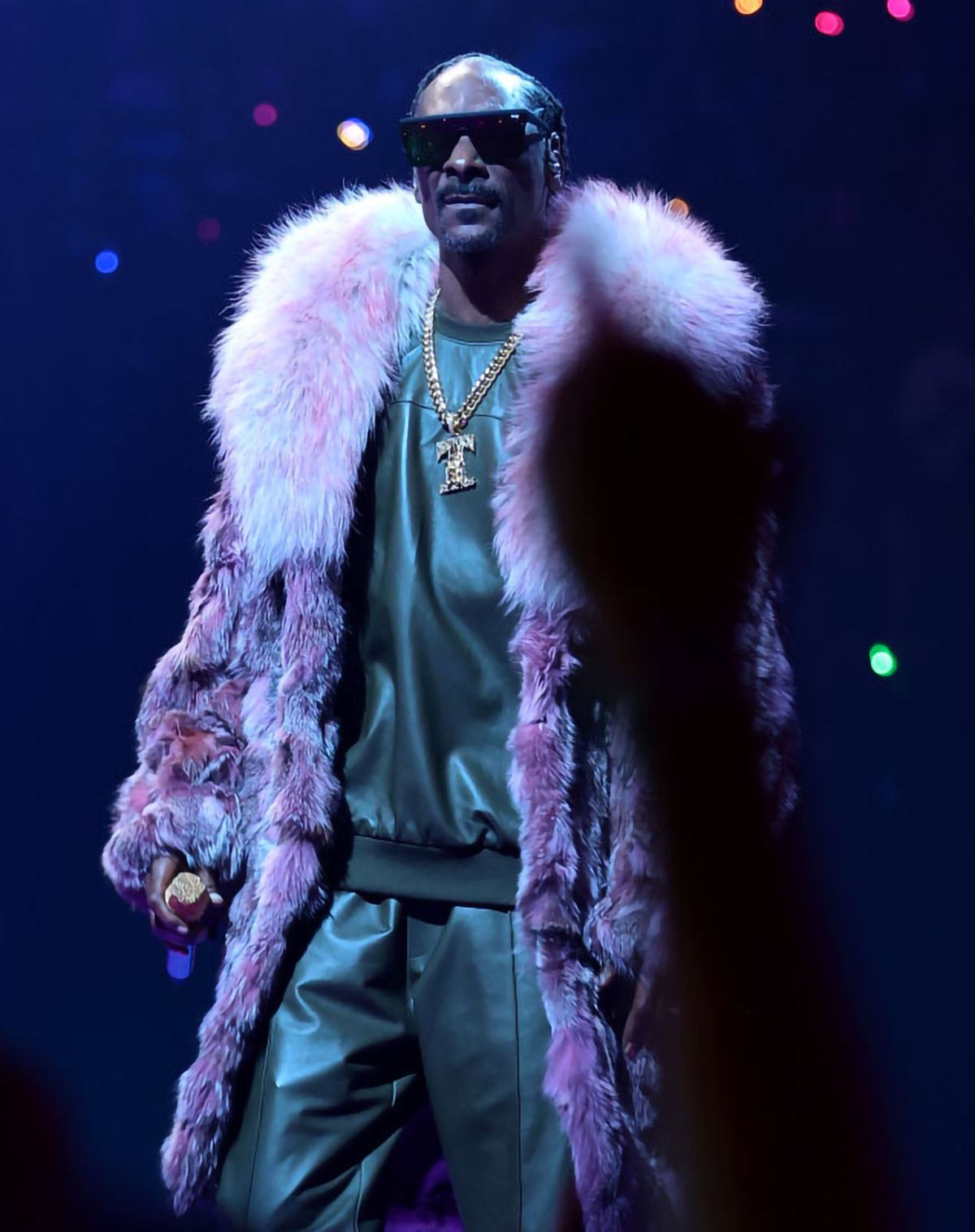

In 2021 the parent company of the massively popular social networking site Facebook changed its name to Meta Platforms. Mark Zuckerberg, its creator and chairman, plans for the company to develop a “metaverse,” a virtual reality (“VR”) world in which all kinds of social and economic business can be conducted by users via VR avatars and digital transactions. Not to be outdone, rapper Snoop Dogg has developed his own “Snoopverse,” and other celebrities are getting in on the VR real estate game as well. Is this the way of the future? Should Christians strap their phones to their faces and dive into the metaverse? And what does this imply about those who can’t afford to do so?

“The poor you will always have with you,” Jesus reminds. But how can the poor and un-tech-savvy navigate a digital and cyber world that changes rapidly and requires specialized training? Rather than fearful, we should be watchful—and generous.

The journey to VR worlds could be bumpy. Meta’s development department posted a $10 billion loss in 2021, and Zuckerberg has stated that losses will substantially deepen in 2022. Not everyone’s doing so poorly, though. Mr. Dogg sold a parcel of Snoopverse real estate in December 2021 … for $450,000. The middle-class masses are not likely to follow anytime soon, let alone the poor. So maybe our meta-future is overhyped, at least for now.

Yet there are many ways in which the future is already here, at least in terms of cashless digital transactions, internet businesses and commodities, and other technological advances in our economies. To the extent that these trends will continue, we can make predictions based on what we know of them in the present. Christians need not fear—nor uncritically participate in—such novelties. But Christians should take the time to understand who thrives and who struggles with them, as well as what promises and dangers they contain.

As St. Paul the Apostle wrote, “Whatever things are true, whatever things are noble, whatever things are just, whatever things are pure, whatever things are lovely, whatever things are of good report, if there is any virtue and if there is anything praiseworthy—meditate on these things” (Philippians 4:8). But how are we to know what things reach these lofty heights? St. Basil the Great, echoing a common early Christian teaching adapted from the Stoics, offers additional guidance: “Health and sickness, riches and poverty, credit and discredit … are not … naturally good, but, in so far as in any way they make life’s current flow more easily, in each case the former is to be preferred.” So, too, when they detract from what is good and godly, they are not “to be preferred.” Thus, any Christian engagement with our digital future requires a prudent and accurate understanding of these technological trends. The good of the underprivileged deserves special attention. What impact do digital technologies currently have on the economy, and what sort of public policies have been proposed to address those left behind by the march of time and tech?

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the digital economy includes “online shopping, digital media, the sharing economy, and other e-commerce developments.” The economic importance of these technologies and processes grows by the day. The digital economy represents a significant share of economic activity, both in its own right and through its effects on traditional methods of production and distribution. In 2020 the digital economy accounted for 10.2% ($2.1 trillion) of U.S. gross domestic product. It supported 7.8 million jobs and generated $1.1 trillion in compensation. It grew 6.3% per year from 2012 to 2020, roughly three times as fast as the overall economy. Clearly, the digital economy has become a “commanding height” of production and exchange.

To ascertain the promises and perils of digitization, we need to explore its effects on the distribution of income and wealth. This can help us understand digitization’s consequences for economic opportunity, especially for the underprivileged. But economics by itself cannot tell the whole story. We also need to explore the effects of digitization on the distribution of power. How digitization affects the scale and scope of government matters just as much as its effects on work, consumption, and investment.

The distribution of income depends on productivity. Labor and capital typically earn the value they add to production processes. A worker who makes $15 per hour for her employer will earn about $15 per hour; a machine that adds $100 per day to a contractor’s business will rent for about $100 per day; and so on. These values are always in flux, in part because the productivity of one factor depends on the availability of the other. Labor is usually more productive in the presence of additional capital, and vice versa. All else being equal, when workers have more or better capital, they produce more and hence earn more.

New investments in the digital economy represent high-tech additions to the economy’s capital stock. We should expect this to make labor more productive, and hence work more remunerative. But things are not quite that simple. Not all workers are equally adept at using this new high-tech capital. We also need to consider the laborer’s accumulated human capital—the techniques and skills that make workers more valuable, especially in the presence of specialized production processes. The digital economy requires specific forms of human capital. Not all workers will have it.

The digital economy requires specific forms of human capital. Not all workers will have it.

Entrepreneurial ability, creativity, adaptability, and overall tech-savviness are crucial for workers looking to create value in today’s increasingly digitized economy. Workers with human capital specialized to yesterday’s production processes could fall behind. This is a familiar story in the history of economics. Economic restructuring, or “creative destruction,” is necessary for economic growth. While it creates many more “winners” than “losers,” the hardship of the latter should not be minimized. The automobile and Henry Ford’s assembly line meant monumental improvements to overall quality of life, but it also put many blacksmiths and horse breeders out of work. Similarly, it’s unlikely many midcareer coal miners or day laborers can run a metaverse boutique or trade cryptocurrencies. It seems inevitable that digitization will contribute to economic inequality.

But is it inevitable? A closer look reveals some countervailing forces. If recent innovations in payment technologies become widely adopted, digitization could radically expand access to the financial system. Peer-to-peer exchange and “crowdsourced” lending, which eschew traditional financial-sector middlemen, could transform the lives of those poor in collateral but rich in ideas. Formal credentials, such as a university degree, matter less in a digitized economy. There are many talented and ambitious youngsters who cannot afford a four-year degree but can have a go at e-commerce. The previously mentioned traits of “entrepreneurial ability, creativity, adaptability, and overall tech-savviness” are much more likely to be evenly distributed throughout the population than is wealth in our pseudo-meritocracy. The digital economy will not be an egalitarian paradise. But it could be more equal—and, more importantly, less impoverished—than what we have now.

You could tell a similar story about political power. Some aspects of the digital economy select for centralization and hierarchy. Others portend radical devolution and autonomy. Predicting which forces will prevail is all but impossible. But we can understand how they work, which offers valuable guidance.

On the one hand, the digital economy makes top-down regulation easier. James C. Scott, an anthropologist and political scientist, coined the term “legibility” to describe how governments try to rationalize the societies they oversee. As digitization proceeds, politicians and bureaucrats will find much of the work has been done for them. Digitized production and exchange leave records that are often easier to trace than low-tech paper trails. That which can be measured and recorded can be controlled. The governing classes are more than happy to let the legibility-enhancing tendencies of the digital economy do their work, because greater legibility means easier social control.

On the other hand, digitization could yield technological advances that frustrate the ambitions of would-be technocrats. Blockchain technology is an obvious example. By facilitating secure, anonymous peer-to-peer exchange, blockchain shields the identities of transactors from prying eyes. Governments could, of course, punish vendors merely for accepting cryptocurrency, but this extraordinary step is very costly. Bundled with improvements in cryptography, many parts of the digital economy could become ungovernable.

Imagine a new, independent class of proprietors with unmediated access to capital, cryptographically protected against government expropriation. Political philosophers going back to Aristotle believed a secure middle class is the best guardian against tyranny. More recently, Christian intellectuals such as Hilaire Belloc and G.K. Chesterton argued that political and economic freedom depend on widespread access to productive assets. While they occasionally indulged too deeply in their romantic visions of free yeomanry, some of their insights concerning the relationship between liberty and human flourishing could find expression in the digital economy. Instead of creating the conditions of dependence and servility, digitization could be a new foundation for ordered liberty.

The Pros and Cons of a Digital Dollar

The conflicting forces unleashed by digitization are particularly clear in the debate over central bank digital currencies. About 80 nations, representing 90% of global income, are exploring a digitized form of national money. In the United States, the Federal Reserve is interested in the idea but has not yet taken concrete steps to create one. Fed officials should think carefully before they do.

Electronic money is nothing new. Almost everyone with a checking account has used it at some point. Digital dollars are already here in the form of electronic bank balances. But central bank digital currencies are different. If the Fed creates a digital dollar, those liabilities will be claims not on private banks but on the central bank.

A public digital dollar has several benefits. It can lower the transaction costs of payments processing, increasing the efficiency of both national and international economic activity. The resources saved through reduced transaction costs can then be put to other, better uses. Everyone is wealthier. For those concerned with equality, a public digital dollar offers another way the underprivileged, and especially the unbanked, can access the financial system. Central banks can offer direct individual accounts, unconstrained by profitability and with minimal hassle. Financial inclusion is important, even apart from efficiency considerations.

But a public digital dollar could have major costs as well. These costs depend on whether we get a “wholesale” or a “retail” central bank digital currency. The former is restricted to financial institutions. The latter is available to the public. In the limit, a retail digital dollar could assign an account to every citizen and permanent resident.

If this seems too good to be true, it may well be. The retail option is much more dangerous, both politically and economically. While a wholesale digital dollar largely functions to improve interbank settlement (the process by which banks clear each other’s liabilities), a retail digital dollar could give the central bank a frightening level of control over the economy.

Suppose the central bank wanted to “stimulate” the economy by imposing a negative interest rate policy. The Fed could deduct 2% of your account balance over the course of a year to incentivize spending rather than saving.

If a retail digital dollar is widely used, financial transactions essentially become public record. There is no possibility for privacy in these circumstances. The central bank would be able to see everything. And what they see, they can control. Remember, from an accounting standpoint, a central bank digital currency is a liability of the central bank. But that liability does not come with a corresponding legal duty to maintain the nominal value of account balances. Suppose the central bank wanted to “stimulate” the economy by imposing a negative interest rate policy. The Fed could deduct 2% of your account balance over the course of a year to incentivize spending rather than saving. The more households and businesses use a central bank digital currency, the more feasible this kind of technocratic interference becomes.

Even more worrying is the prospect of the Fed meddling with digital dollar balances for partisan reasons. In recent years there has been noticeable mission creep at the Fed. The central bank started pursuing objectives far removed from its monetary and regulatory mandates, such as climate change and racial justice. Regardless of these causes’ merits, they hardly fall under the Fed’s purview. Furthermore, they could very easily be used to perpetuate new injustices. If the Fed controls the payment system, as it would through a retail digital dollar, what stops it from selectively hampering payments processing for politically disapproved firms? Fossil fuel companies or businesses with insufficient (as determined by the Fed) minority ownership and upper management representation could be severely disadvantaged. What started as a project for empowerment and financial inclusion too easily ends with increased economic and political power for central bankers, who already had plenty of both.

For central bank digital currencies, everything depends on the form they take and how they are used. This is a microcosm of the whole digital economy. The humane and egalitarian possibilities are real. So are the domineering and hierarchical ones. Reasonable people can disagree over which outcome is likely to prevail. A prudent approach would distinguish those features of digitization most likely to make productive property more accessible to the disadvantaged from those most likely to imprison us in a financial panopticon.

Discernment in the Digital Economy

Given this mixed bag of possibilities, we recommend that Christians take a cautiously optimistic approach. It will not do to uncritically praise or reject our coming economy. We must practice discernment through the ancient ascetic practice of nepsis, or “watchfulness,” carefully examining our thoughts and passions to ensure they truly reflect a sober, reasonable, and righteous account of the world and our hearts. Ancient Christians practiced this prayerful meditation as a way to bring “every thought into captivity to the obedience of Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:5). This ancient asceticism still holds the key to prudent living in our economies today as well as in the future.

Because specialized human capital will determine a person’s ability to thrive in the digitized economy of tomorrow, those who are able should look for opportunities to help the poor and the marginalized increase their skills so as to adapt to these technological trends. We can and should celebrate the economic enrichment created by digitization. But those on the losing side of creative destruction will need supportive communities—families, friends, local churches and parachurch ministries—genuine “neighbors” in the sense of Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37), in order to get back on their feet.

It will not do to uncritically praise or reject our coming economy. We must practice discernment through the ancient ascetic practice of nepsis, or “watchfulness."

At the same time, we must also be discerning about the forms digital transactions take, whether so autonomous as to lack legal safeguards or so thoroughly under the state’s surveillance, as in the case of retail digital dollars, as to afford no space for privacy. Christians with the know-how necessary to use emerging technologies have a duty to share that knowledge with those in need, denying aspiring tyrants the possibility of meddling in every transaction. Note well: This tyranny is precisely the form St. John ascribes to the “beast coming up out of the earth”—namely, that “no one may buy or sell” without its permission (Revelation 13:11, 17). One need not take an apocalyptic view of the present or near future to see this as a warning against all-embracing economic tyranny at any time in history. Once again, we must practice discernment in order to know what things are true, noble, just, pure, lovely, virtuous, and praiseworthy … and what are their opposites.

There is an additional dynamic that Christians cannot overlook. Many of the most vulnerable people in the midst of rapidly advancing technological change are the poor (including disproportionately marginalized groups, such as ethnic minorities), the disabled, and the elderly. In every case, the feeling of falling behind adds an additional barrier. Poverty cannot be reduced to material insufficiency alone. It includes the debilitating stress of living paycheck to paycheck—if one is even fortunate enough to have a paycheck—always anxious about how to provide for oneself and one’s family. The Psalmist says that the Lord “heals the brokenhearted / And binds up their wounds” (Psalm 147:3). So also the Law teaches that “man shall not live by bread alone” (Deuteronomy 8:3). All people, rich and poor, able-bodied and disabled, those of sound mind and the mentally ill, the young and the elderly, need the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the love of Christians, the Church, in order to flourish. Christians should lead the way in fortifying the brokenhearted, healing their wounds, and feeding people’s souls with the Word of God. When people have that kind of support, they have one less barrier in the way of their economic improvement as well.

Subsidiarity

When it comes to the digital economy, we cannot predict whether the forces of empowerment or servility will prevail. Both are real. Both can transform economics and politics. And both entail serious moral consequences. Aided by contemporary social science, sober-minded Christians are uniquely positioned to guide digitization along paths that respect human dignity.

Subsidiarity, an important principle from Catholic social teaching, holds that authorities should govern at the smallest scale possible. The Reformed concept of sphere sovereignty offers similar guidance: The social world is composed of multiple overlapping spheres or areas of interaction, each containing authorities with a legitimate domain. Similarly, the Orthodox Tradition reminds us of the ascetic core of social life—that in order to live well with others, we must deny ourselves. So, too, every sphere or sector of society must deny its ambition to dominate others. The Church may be all things to all men, but for any other area of society, such pretensions are heretical and dangerous. Christians of all confessions must work together to ensure that the digital economy unleashes human flourishing rather than stifling it. That means advocating and responsibly participating in the uplifting aspects of digitization. It also means critiquing and modeling resistance to the stultifying aspects of digitization.

Christians hoping for a list of licit and illicit digital activities are bound for disappointment. Prudence doesn’t work that way. Instead, followers of Christ must use their practical and moral reasoning to study the consequences of digitization. Conversation and debate in the public square will play an important role in setting the basic legal framework governing the digital economy. For the sake of the least among us, we have a responsibility to ensure that the digitized playing field remains open, competitive, and fair.