We inhabit a political moment that refuses to be taken seriously. Every attempt to take up the genuine challenges our country confronts is obstructed by a stubborn combination of crude cynicism and bitter factionalism. Every appeal to the unifying ideals of the American experience is met with ignorant ingratitude or histrionic despair. We tell the young they are inheriting a garbage heap and then are surprised they want to throw their heritage away. We tell our leaders we want entertainment and then are shocked when they behave like clowns. We confront a vacuum of civic virtue and a dearth of responsible leadership.

Through capsule biographies of great statesmen-thinkers, Daniel J. Mahoney provides examples of the very virtues that can cure what ails the American body politic.

By Daniel J. Mahoney

(Encounter Books, 2022)

It’s hard to know where to begin in taking on such daunting problems. But what if our failure to take our common life seriously is as much a cause as an effect of these civic deformations? What if the place to start is by changing our attitude about the political?

This is the implicit premise of Daniel Mahoney’s brilliant new book, The Statesman as Thinker. On its face the book is an engaging and illuminating study in the highest forms of political leadership. But in its depths it is a call to make some room for an idea of greatness amid our democratic din, and to grasp that political greatness in a free society demands moderation and magnanimity rather than vulgar self-indulgence pretending to be strength.

Such greatness may need to come from above before it can come from below. The vices of democracy are not likely to be best counterbalanced by the democratic multitude to begin with. But a society like ours might learn to take itself more seriously through the leadership of statesmen who take it seriously themselves. And what makes such statesmen possible is above all a particular kind of character—a mix of virtues that is Mahoney’s foremost subject.

To speak of a statesman is unavoidably to sound old-fashioned and out of place, and this is exactly why Mahoney does it. But “statesman” is not just an antiquated way to say “politician” or “leader.” Mahoney has a particular meaning in mind, especially as his subjects are statesmen who were also thinkers. The book’s focus, as Mahoney puts it, is “on those rare and admirable souls who embodied magnanimity tempered by moderation, who embodied the cardinal virtues in a morally serious and realistic way, and whose rare combination of thought and action partook of the philosophical.”

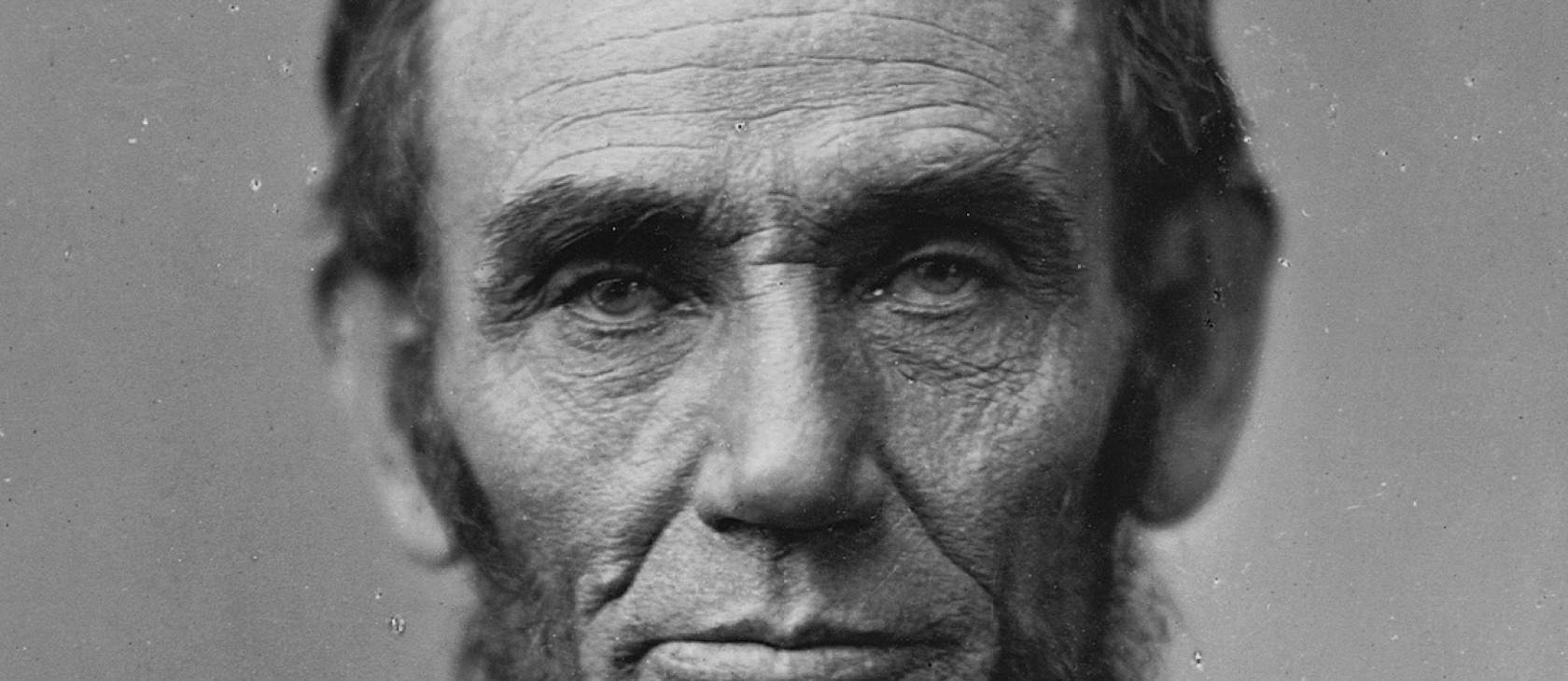

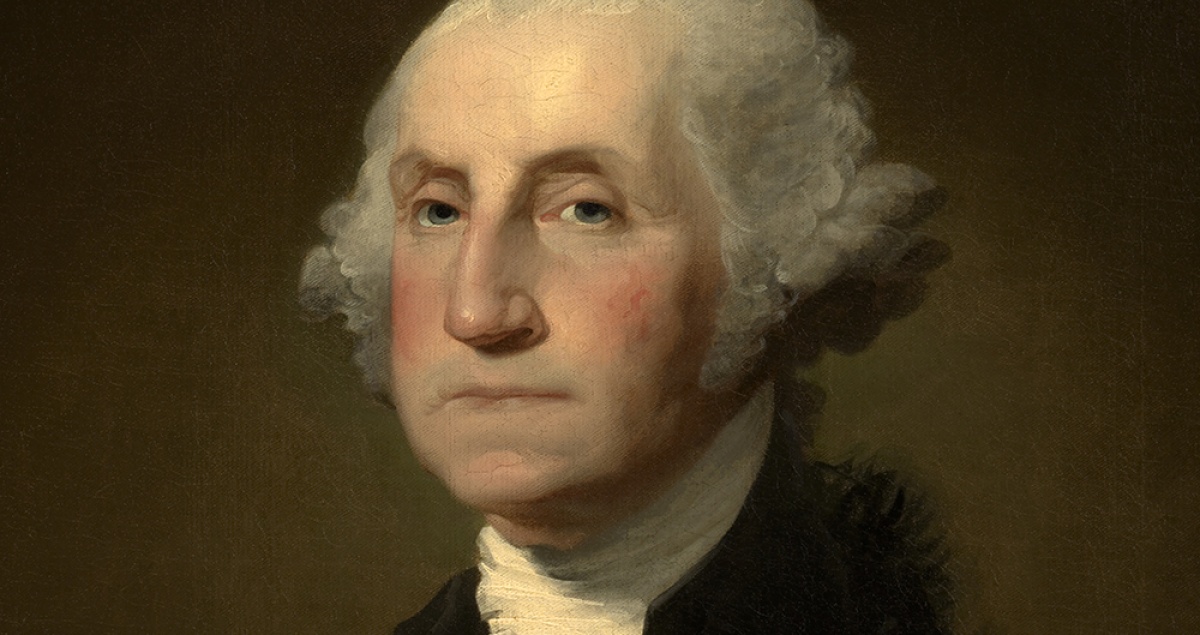

The “rare” in that description is clearly an understatement. The book takes up Edmund Burke, Alexis de Tocqueville, Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, Charles de Gaulle, and Václav Havel, with significant additional discussions of Pericles, Cicero, George Washington, Nelson Mandela, and a few other leaders and thinkers. These are thoroughly exceptional people who led their countrymen in exceptional moments of crisis and need.

Mahoney tells their stories through capsule biographies, with each chapter taking up a particular statesman-thinker. And he observes them through the lens of secondary sources, generally one or two key academic or popular biographies with which each chapter is in conversation. This mode is a little disorienting at first, as each chapter functions as not only a profile but also a kind of book review. But it enables Mahoney to engage one or two key scholars of each of his subjects in ways that clarify his purpose and his point. In some cases, he very much approves of the sources he takes up, as with Greg Weiner’s Old Whigs, which comes up in Mahoney’s discussions of both Burke and Lincoln. But in other cases, he critiques the scholars he leans upon, as with Hugh Brogan’s Alexis de Tocqueville: A Life, which Mahoney deems far too committed to egalitarian platitudes and therefore “woefully unsuccessful” in capturing Tocqueville’s character and ideas.

Some institutions willing to be forthrightly countercultural do teach the virtues as if they were virtues and imbue young people with both gratitude and boldness.

And it is on the character and ideas of each of his subjects that Mahoney dwells in particular. He offers quick surveys of their notable deeds but spends most of his time delving into the sort of person that each of them was—with special attention to temperament, prudence, moderation, judgment, and religious faith.

In most of these respects, Mahoney offers an Aristotelian ideal of the statesman, focused on core virtues that are each understood as lodged halfway between two vices and therefore as calling upon both boldness and restraint. But with his focus on religion, Mahoney goes even deeper and suggests that statesmanship of the sort he outlines is really only possible in a broadly Christian context. Not all his subjects were religious men, strictly speaking, but he argues persuasively that all had theotropic souls and drew their confidence and greatness from wells deeper than their personal ambition.

This is an especially important insight for our times, since it suggests that genuine statesmanship calls for a person not shaped exclusively by our democracy but rather able also to call upon older and more profound sources of formation. The universities of the West used to be able to offer both Christian and pagan paths toward these deep roots of virtue, and several of Mahoney’s subjects were clearly shaped by such learning. But today our universities generally no longer offer us “the counter-poison to mass culture,” as a great teacher once put it. They are instead arenas for full and unabashed participation in that culture, and indeed are home to its most radical wing, and so are far less capable of offsetting its vices.

One of Mahoney’s subjects, Abraham Lincoln, managed somehow to school himself in decidedly premodern modes of character and judgment without the aid of much formal education. Maybe we can hope that future statesmen could do the same, but hoping for another Lincoln hardly seems practical. Rather, it is much more likely that any genuine thinker-statesman in our time will be a product of religious formation—and more specifically, given the particular contours of our society, that he will be a serious Christian. Such formation is uncommon too, of course, but great statesmen are always uncommon. What matters is that some institutions willing to be forthrightly countercultural do teach the virtues as if they were virtues and imbue young people with both gratitude and boldness. Those who persist in such work in our day may be found mostly in tradition-minded religious communities.

This points to a further lesson illuminated by Mahoney’s mode of argument. His subtitle—“portraits of greatness, courage, and moderation”—is intentionally provocative and paradoxical. Are great men really moderate? Mahoney answers decisively that they are. He contrasts, for instance, the characters of Napoleon and George Washington, and suggests that only Washington was truly a noble statesman in the end, as Napoleon embodied, in Mahoney’s telling, “greatness without moderation.”

Moderation is always the most challenging of the statesman’s virtues, because it requires restraint of people with the capacity to act boldly. And moderation is all the more difficult in democratic times, because in such times it calls not only for restraining elite action but also for restraining public passions—or at least for satisfying public demands in only partial ways. Indeed, the absence of moderation may be the most important and most consequential of our civic vices in this moment, and the one that most urgently calls for leadership by thoughtful statesmen.

Moderation of this sort is not a mode of action but a character trait. And in the end Mahoney’s profiles teach us that the same is true of greatness and courage. They describe human individuals, not a style of leadership. Each of the profiles that compose the book is a character study, inquiring into the influences that formed a great man: his family life and his friendships, his attitude toward his country, the place of philosophy and of religion in his thinking, the nature of his passion and ambitions, and the kind of disposition with which he approached his significant place in the world. Each implies that character is destiny and that a leader of truly great character can lift up the destiny of an entire nation.

This only further highlights the depths of the difficulty we confront now, as our culture works incessantly to obstruct the formation of the kind of character Mahoney celebrates, and to mock the virtues he would have us champion. A great statesman always stands apart some from the mainstream of his culture, but in our time the capacity to stand apart, far from the tweeting crowd, is harder than ever to muster. Our egalitarianism, for all its virtues, devalues such distance and scorns the desire for it.

This is not a new problem. And in taking it up, Mahoney is working in the great tradition of some of the very thinkers to whom he calls our attention. In fact, Mahoney’s own project in this book is perhaps best articulated in his description of Tocqueville’s purpose: “This conservative-minded liberal was a party of one,” Mahoney writes, “rejecting both the perils of socialist servitude and the temptation of conservative authoritarianism.” Rather than either of those, Tocqueville’s writing suggests a man “loyal to his principles, and committed to a future where liberty and a modicum of greatness might coexist.”

Moderation is always the most challenging of the statesman’s virtues, because it requires restraint of people with the capacity to act boldly.

This is precisely the vision underlying Mahoney’s own work, and precisely the vision necessary to enable our society to take itself seriously again. Mahoney, following Aristotle, describes the political life of a free society as “a humanizing arena for moderating conflict and pursuing the civic common good.” This is not how most Americans would be likely to describe our politics now, but it is how we should all understand it, and seek to engage in it.

The resources to reach that understanding are available to us, as Mahoney seeks to show. They are present in the living tradition we inherit as Americans. But inheritance is an active process, and it requires a willingness to appreciate that modicum of greatness present in the statesmen of our past, to admire it, and to be grateful for it in a way that might allow it to form our own characters and souls and those of our leaders. Mahoney is most impassioned when making the case for this kind of openness, as he does at a number of points in the book, and when pointing out the shallowness and the ingratitude of what he calls today’s “highly ideologized climate marked by collective self-loathing and an unremitting desire to repudiate the inheritance of the past.” In such a culture, Mahoney continues, “ingratitude becomes inseparable from vulgar and destructive nihilism.” In the end Mahoney’s learned, thoughtful, and enlightening book is an antidote to such nihilism and a recipe for a more proper disposition toward our common life.

That disposition is not utopian. On the contrary, it is very realistic. “It remains our obligation to reaffirm the real in a spirit of gratitude for what has been passed on by our forebears as a precious gift,” Mahoney argues. To cure what ails us, we must have some idea of what health looks like, and that is what this book provides.

Grasping what the highest sort of statesmanship involves is not the same as bringing it into being, of course. Real greatness is inherently rare and fleeting. “Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm,” as James Madison warned, and we are lucky to possess a system of government that does not depend upon their being at the helm in every moment. We should not envy the America of the mid-19th century, which required a Lincoln to arise in order for it to survive. That society was horribly broken in many ways that we are not. But we should be aware that we are in some ways broken, too, and that we could benefit from thoughtful statesmanship of a sort that will not arise if we are not open to it, aware of its nature, and ready to allow it to moderate our democratic passions and excesses.

We should recognize, in other words, that the politics of a free society is a weighty endeavor that deserves to be taken seriously.