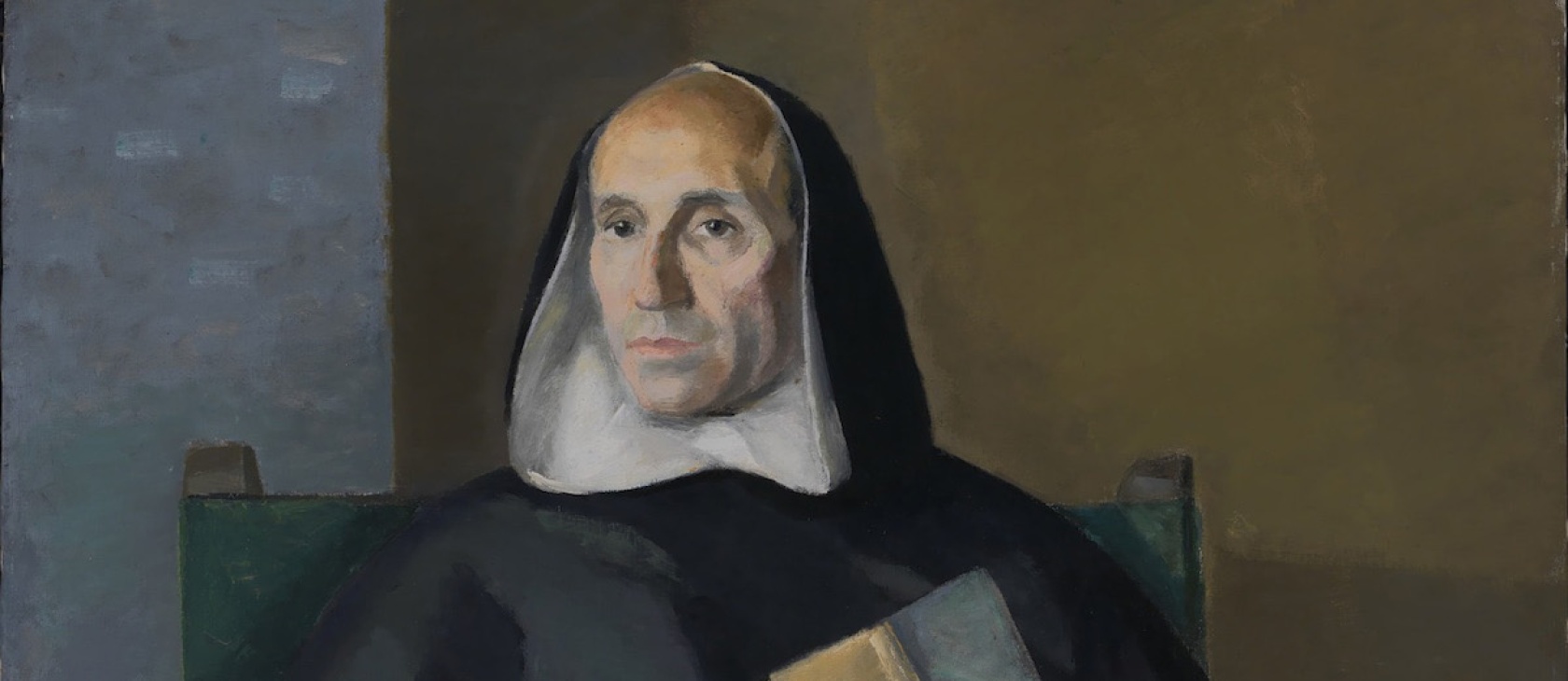

Francisco de Vitoria probably isn’t a name that rolls off the lips or even vaguely registers in the minds of most, but he is worth knowing. This highly influential 16th-century Spanish Dominican priest is known as no less than the “father of international law.”

What does a late Renaissance Catholic priest have to do with the “liberal tradition”? When you’re also the founder of the “School of Salamanca,” more than you think.

Born in Burgos, Spain, in 1483, Vitoria was one of the most influential theologians of his generation. He was the founder of what became known as the “School of Salamanca,” based at the University of Salamanca (founded in 1218), where he chaired the religion department from 1524 until his death in 1546. Vitoria’s impact on law, theology, philosophy, and human rights is difficult to overstate.

The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V regularly consulted Vitoria, who became an indispensable counsel on crucial matters dealing with the expanding Spanish Empire. Vitoria advised the emperor on everything from just war to proper treatment of the native peoples of the Americas. He insisted that the natives, despite their status, and regardless of whether they were Christians or even considered inferior, could not be deprived of their property rights. Their status should have no impact on their natural rights to possess and use goods. They were human beings with fundamental rights based on Scripture, reason, and natural law. They were rightful owners of their property, and the Spanish Empire could not deny them. All were made in the imago Dei.

Vitoria borrowed from Aquinas and a Scholastic understanding of the inherent dignity of human beings, as well as the concept of ius gentium (“the law of nations”). His two most significant works were his De Indis and De iure belli. De Indis is most integral to Vitoria’s defense of the rights of natives, which included their right not to be forcibly converted to the Christian faith. Like all human beings, they needed to accept the faith by their own free will, not under compulsion.

Scholar Victor Salas observes of Francisco de Vitoria that in first encountering the great theologian’s writings one expects a figure who, being quintessentially Scholastic, is “an even-tempered and dispassionate intellectual who treats all questions with equanimity and is swayed only by the exigencies of reason itself.” But that is not always what one finds, as Vitoria was outraged at Spain’s mistreatment of its alleged “inferiors.” Salas points to correspondence on the Spanish confiscation of Peruvian property in which Vitoria expressed his disgust to his religious superior. The usually calm Vitoria fulminated: “I must tell you, after a lifetime of studies and long experience, that no business shocks me or embarrasses me more.” The “very mention [of their mistreatment] freezes the blood in my veins.”

As Salas notes, Vitoria came to the defense of the American Indians “in the only way he could,” as a Scholastic academic wielding the rich resources of the Catholic intellectual tradition, while at the same time righteously railing against the unjust violation of the intrinsic dignity of New World peoples.

In this, Vitoria differed markedly from the likes of his contemporary Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, who viewed Native Americans as almost subhuman, beyond reason and natural slaves. Sepulveda had insisted that it is “naturally just and beneficial for both sides that men upright in virtue, intelligence, and humanity rule over inferiors.” Vitoria vehemently disagreed.

Vitoria is not without some controversy, however. Some modern scholars, such as Antony Anghie, author of Imperialism, Sovereignty, and the Making of International Law, and Steven Newcomb, author of Pagans in the Promised Land, have taken a very different view, arguing that Vitoria’s ideas actually legitimized conquest of the natives. They assert that Vitoria’s concept of jus gentium meant that war could be waged against Native Americans if they resisted Christian evangelization.

That is a subject of debate, often hinging on hair-splitting over the exact applications of just war doctrine in numerous complex situations. It was no easy task for a mere mortal, even a theologian as accomplished as Francisco de Vitoria, to forge a new way of looking at law from a truly international perspective. Many of Vitoria’s detractors are the same who begrudge the Catholic Church credit on human rights matters and are often ignorant of the church’s nuanced teachings. Vitoria today is interpreted as everything from a conservative reader of St. Thomas to a “progressive thinker” way ahead of his times in condemning what today would be regarded as racist thinking toward natives.

Yet, despite the obstacles he had to overcome, struggling to operate under the societal pressures and within the standards of his day, Vitoria has had a profound influence on law and philosophy. His work was carried on by other church notables who picked up his mantle, particularly fellow Dominicans Melchor Cano (1509–1560) and Dominic de Soto (1494–1560). Their renowned School of Salamanca would play a crucial historical role in the development of law, theology, and philosophy beyond the walls of the church. In the evolution of the recognition of basic human rights and international law, Francisco de Vitoria was an early and significant freedom fighter—yes, within the liberal tradition.