The metaverse does not exist, yet we’ve been talking about it for 30 years. This should not surprise, as its first appearance in the English language is in a work of fiction. The term’s precursor, “cyberspace,” is the invention of American-Canadian writer William Gibson, who introduced it in his 1982 novella, Burning Chrome, and popularized it in his 1984 novel, Neuromancer. But “metaverse” itself was first minted by the American science fiction writer Neal Stephenson and released into circulation between the pages of his 1992 novel, Snow Crash. Snow Crash is the most fitting analog to what is being proposed by the dreamers of contemporary Silicon Valley: a virtual-reality-based internet navigated by digital avatars—graphical representations of its denizens—mediated through headsets worn by consumers in the real world.

The best science fiction writers create dream worlds that promise an escape from the limits of being human. Yet God is still God, outside all created realities and unrealities, and before whose providential control even the metaverse must yield.

In 2021, Facebook—famous for its eponymous social media platform as well as Instagram and WhatsApp—renamed itself Meta to “reflect its focus on building the metaverse.” When Stephenson was originally planning what would become Snow Crash, he conceived of it as a sort of modest metaverse, a computer-generated graphic novel, but abandoned it due to technical limitations and completed it in more conventional novel form. Now some of the world’s most successful companies are giving it a go with 30 additional years of technological development and considerable investments of financial, human, and reputational capital.

That what is a dream today may soon be a reality should not surprise us, for as T.E. Lawrence observed, “The dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dream with open eyes, and make it possible.” What is surprising, and deeply troubling, is the prospect that the new reality long incubated in dreams may give birth to a world in which dreams increasingly displace reality, for dreams can be nightmares.

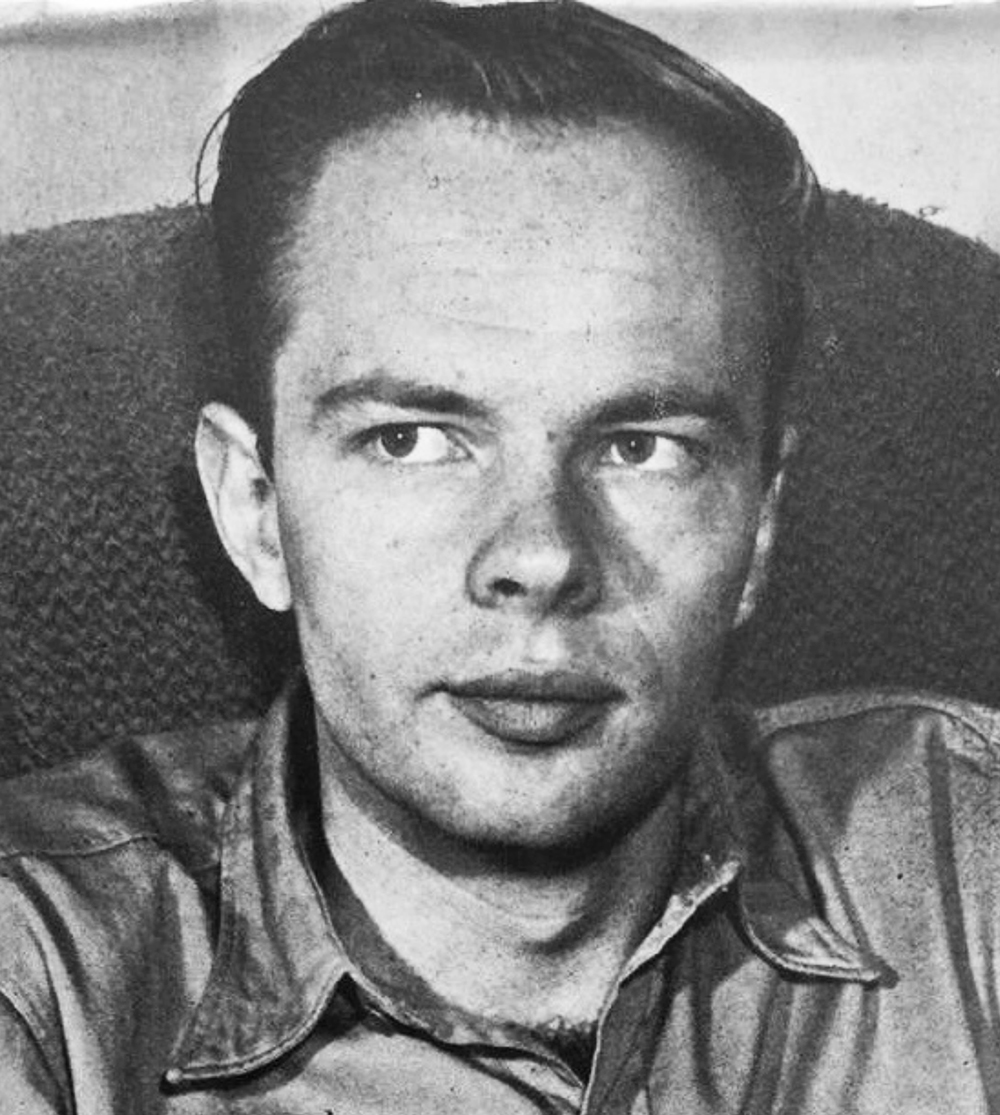

This terrifying possibility animated the writing of someone many would consider the greatest of American science fiction writers, Philip K. Dick, who spent his entire career preoccupied by two questions: What is reality? and What constitutes the authentic human being? These perennial questions became particularly urgent given the technological context of the information age, and he believed science fiction writers were uniquely well suited to answer them

because unceasingly we are bombarded with pseudo-realities manufactured by very sophisticated people using very sophisticated electronic mechanisms. I do not distrust their motives; I distrust their power. They have a lot of it. And it is an astonishing power: that of creating whole universes, universes of the mind. I ought to know. I do the same thing.

Philip K. Dick first spoke these words, appropriately enough, at a science fiction convention in a talk titled “How to Build a Universe That Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later.” The year was 1978 and the “sophisticated electronic mechanisms” were the technologies utilized by the entertainment and mass media industries of his day. Of those, especially troubling for him was television:

Words and pictures are synchronized. The possibility of total control of the viewer exists, especially the young viewer. TV viewing is a kind of sleep-learning.... Recent experiments indicate that much of what we see on the TV screen is received on a subliminal basis. We only imagine that we consciously see what is there. The bulk of the messages elude our attention; literally, after a few hours of TV watching, we do not know what we have seen. Our memories are spurious, like our memories of dreams; the blanks are filled in retrospectively. And falsified. We have participated unknowingly in the creation of a spurious reality, and then we have obligingly fed it to ourselves. We have colluded in our own doom.

Mark Zuckerberg, founder and CEO of Meta, promises that the metaverse will be an even more immersive experience: “You’re really going to feel like you’re there with other people. You’re not going to be locked into one world of platform.” While Philip K. Dick did not speak directly to the metaverse as imagined by Stephenson in the 1990s or Silicon Valley today, he did return throughout his career to the possibility of similarly immersive alternative realities, pointing primarily to their potential peril but also to an often ambiguous promise. A recurring feature of Dick’s imagined realities was, like Zuckerberg’s vision for the metaverse, a feeling of being “with” others.

Can-D and the Neo-Christians

The most vivid and terrifying visions of alternative realities in the works of Philip K. Dick appear in his 1965 novel, The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch. It’s set in a future world affected by climate change in ways even teen climate activist Greta Thunberg couldn’t begin to imagine. During daylight hours, you will be incinerated walking down the street if you aren’t wearing cumbersome cooling equipment. To ease the burden on a rapidly deteriorating planet, the United Nations conscripts much of Earth’s population into the colonization of nearby planets. Conditions on these planets are so underdeveloped and hostile that the now cursed earth is by comparison a garden of delights.

To cope with their miserable existence, colonists escape into endemic drug use. Their drug of choice? Can-D. Can-D is a hallucinogenic with both unusual paraphernalia and a twist. The paraphernalia? Perky Pat Layouts. These consist of miniature apartments, furnishing, cars, etc. Think Barbie Dreamhouse except, instead of Barbie and Ken, the sole occupants of this alternative reality are Perky Pat and her boyfriend, Walt. Now for the twist. Users of Can-D chew it together before the layouts and share an experience of this simulacra of the Earth prior to its ecological collapse.

Many colonists, like Sam Regan, begin to believe the shared hallucination is real:

He himself was a believer; he affirmed the miracle of translation—the near-sacred moment in which the miniature artifacts of the layout no longer merely represent Earth but became Earth. And he and the others, joined together in the fusion of doll-inhabitation by means of Can-D, were transported outside of time and local space.

What began as an escape, a fiction, becomes a religion of sorts with theological controversies about the precise nature of the “translation,” complete with discussions of accidents and essences! Colonists speak of the experience as one of putting on “imperishable bodies” and of its being “eternal” in some sense. Meanwhile, their hovels are falling into disrepair and all work terraforming their hostile environment is abandoned. The only colonists who offer any resistance are the Neo-Christians, who see clearly the idolatry involved, a grotesque parody of the Faith, and its spiritually destructive consequences. Many of them give in to temptation nonetheless.

Can-D presents a nightmare vision of just how terrifying an alternative world where “you’re really going to feel like you’re there with other people” can be. In short, a simulated community can have disastrous consequences in the real world as people retreat from it into their dreams.

The Promise of Eternal Life

There is another vision of the metaverse, however, one described by Matthew Ball, author of The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything:

I describe it as a massively scaled and interoperable network of 3D-rendered, real-time virtual worlds, which can be experienced persistently and synchronously by an effectively unlimited number of users, each with an individual sense of presence.

What I am effectively describing is a virtual plane parallel to the physical world, which, in addition to being able to do many things that we can’t do in the real world, replicates it. We all participate at the same time, with no cap to what we can do, and why we can do it, and how many people can participate.

This is a vision of the metaverse that is not merely an alternate reality within which simulated communities exist but parallel virtual realities unburdened by the constraints of creation itself. It is analogous not to Can-D as described in The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch but to its competition, Chew-Z, whose slogan is “Be choosy. Chew-Z.” The industrialist Palmer Eldritch returns from a neighboring star system with the new alien hallucinogen and rapidly brings it to market.

Chew-Z does not require the use of external layouts and thus is completely separate from reality itself. As Palmer Eldritch claims: “It will only be after a few tries that they realize the two different aspects: the lack of time lapse and the other, perhaps the more vital. That it isn’t fantasy, that they enter a genuine new universe.” The experience of Chew-Z is near instantaneous within our reality. “When we return to our former bodies—you notice the use of the word ‘former,’ a term you won’t apply with Can-D, and for good reason—you’ll find that no time has passed.” Chew-Z is a gateway to “a virtual plane parallel to the physical world” with “an effectively unlimited number of users, each with an individual sense of presence.” The tension within this description is noted by Leo Bulero, chairman of the board of Perky Pat Layouts, who rages, “But the worst aspect of Chew-Z is the solipsistic quality. With Can-D you undergo a valid interpersonal experience.”

While Can-D offers a grotesque parody of religious transcendence, Chew-Z advertises itself with the boldest of blasphemies: “GOD PROMISES ETERNAL LIFE. WE CAN DELIVER IT.” There is, of course, a catch, as there always is when promises such as these are trusted. There’s always a cost to attempting to circumvent the order of creation and seeking to free ourselves of “caps to what we can do, and why we can do it.” New worlds offered to us are always tethered to their authors; lurking behind each is its own Palmer Eldritch.

The Banality of Being Yourself

There is, as we have seen, possibilities for both pathetic and sinister metaverses: alternate realities both escapist and solipsistic. What will perhaps come first, however, is the banal.

In 2017 the retail giant Walmart, working with Mutual Mobile, designed a demo of “an immersive VR simulation that gave users an idea of a smart shopping experience.” The demo was designed under a tight deadline for the South by Southwest (SXSW) festival. It featured a poorly rendered shopping cart that the user pushed down poorly rendered aisles as they filled their virtual shopping cart with virtual milk and wine. While doing so, a floating virtual clerk, or rather the clerk’s head and torso, assisted by providing recommendations and reminders to the virtual shopper. How this was an improvement over now ubiquitous online grocery shopping and delivery remains a mystery to this day.

What began as an escape, a fiction, becomes a religion of sorts with theological controversies about the precise nature of the “translation,” complete with discussions of accidents and essences!

A similarly banal, but vastly more useful, innovation lies at the heart of Philip K. Dick’s 1966 short story “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.” The story is more widely known through director Paul Verhoeven’s 1990 film Total Recall starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. (The less said about the 2012 remake the better.) In both the story and film, the working-class protagonist dreams of going to Mars, but his wife continually dissuades him. He decides instead to visit Rekall, a firm that implants artificial memories of popular vacation destinations, to fulfill his desire while avoiding confrontation with his wife. In the 1990 film, the recall virtual travel agent makes a successful upsell by asking the following question: “What is it that is exactly the same about every vacation you’ve ever taken?” The protagonist is flummoxed but bemused. With the hook set, the salesman seals the deal:

You. You’re the same.

(pauses for effect)

No matter where you go, there you are. Always the same old you.

(grins enigmatically)

Let me suggest that you take a vacation from yourself. I know it sounds wild, but it’s the latest thing in travel. We call it an “Ego Trip.”

This “vacation from yourself” involves selecting a new, exciting identity and a new, attractive romantic partner. An unforgettable vacation otherwise impossible in the real world, in your real life.

These imagined worlds, these science fictions, show us possible metaverses that arise out of the desires of persons. In so doing they provide fertile ground for pondering the meaning of the metaverse in general.

The Wachowskis’ 1999 film, The Matrix, has proved an enduring source of inspiration and speculation on the philosophical questions that often arise when considering alternative and simulated realities. In its most famous scene, the leader of the resistance, Morpheus (Lawrence Fishburne), offers the protagonist Neo (Keanu Reeves) a choice between two pills: red to reveal the truth about his known reality, and blue to return to it without such knowledge. The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek sees this as a fundamentally false choice:

Of course, the matrix is a machine for fictions, but these are fictions which already structure our reality. If you take away from our reality the symbolic fictions that regulate it, you lose reality itself. I want a third pill … a pill that would enable me to perceive not the reality behind the illusion but the reality in illusion itself.

The Unreality of Artificial Reality

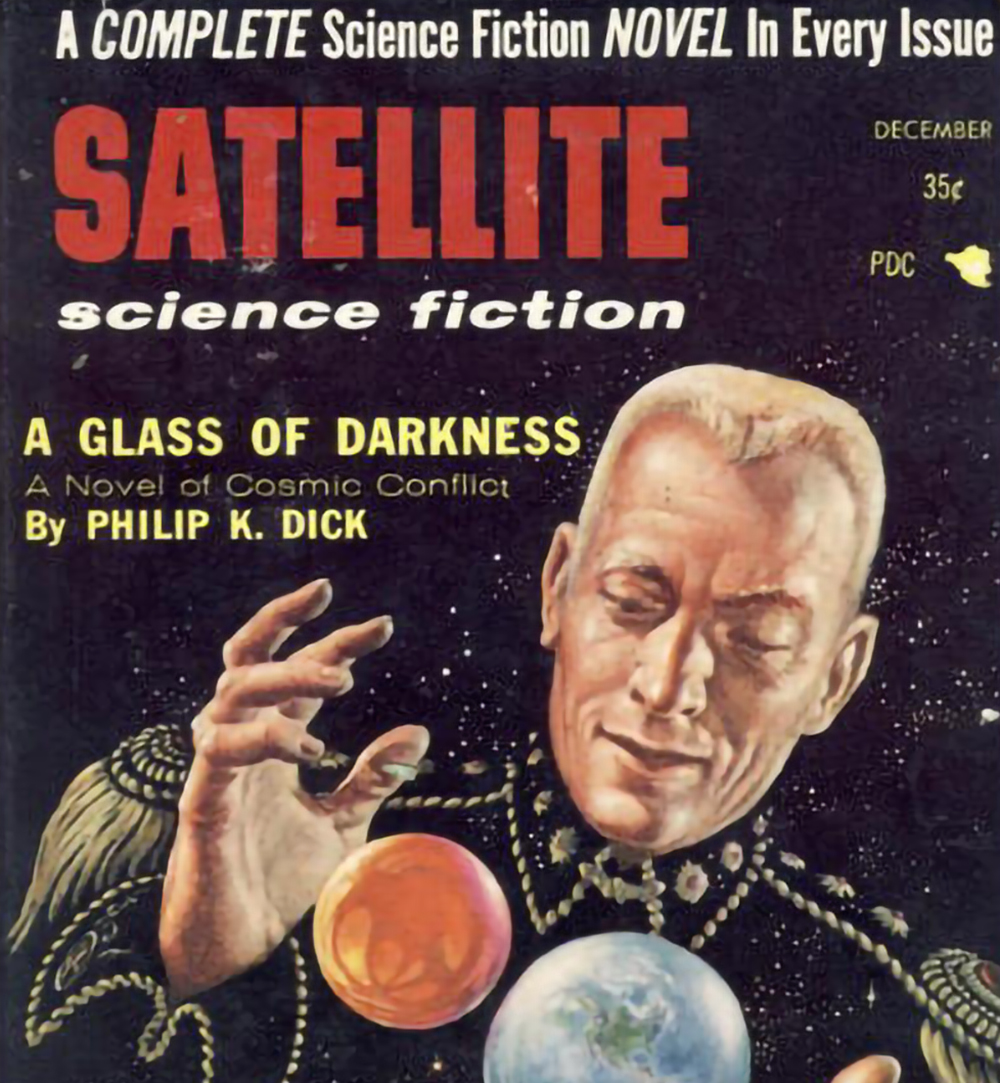

The metaverse, as of yet, does not exist. It’s a fiction built upon science fiction. A dream with dreamers of the day dreaming it who, if anyone can, will make it possible. The meaning of the metaverse is thus the meaning of the desires for the metaverse. Where does one find the reality in illusion itself? In the alluring hopes and haunting fears of the science fiction from which it first arose. In mass-market Ace paperback doubles.

There is a fundamental disjunction, however, between the mood of our greatest science fiction writers and our dangerous dreamers of Silicon Valley on the “meaning” of alternate realities, even as the sense often overlaps.

Faith placed in the metaverse to emancipate us from the constraints of creation and providence is a faith misplaced, one built on the shifting sand of the whims and capacities of those who fashion them.

Philip K. Dick, for example, knew more than our technological visionaries. He had the wisdom that came only from experience:

And—and I say this as a professional fiction writer—the producers, scriptwriters, and directors who create these video/audio worlds do not know how much of their content is true. In other words, they are victims of their own product, along with us. Speaking for myself, I do not know how much of my writing is true, or which parts (if any) are true. This is a potentially lethal situation. We have fiction mimicking truth, and truth mimicking fiction. We have a dangerous overlap, a dangerous blur. And in all probability it is not deliberate. In fact, that is part of the problem. You cannot legislate an author into correctly labeling his product, like a can of pudding whose ingredients are listed on the label … you cannot compel him to declare what part is true and what isn’t if he himself does not know.

Many artists and writers have a famously tenuous relationship to reality. This may be a product of temperament or a powerful imaginative capacity. Philip K. Dick is no exception. Throughout his life he struggled with both mental illness and substance abuse. In the very speech in which he acknowledges the “dangerous blur” between truth and fiction in “How to Build a Universe that Doesn’t Fall Apart Two Days Later,” he relates several improbable quasi-mystical experiences. His Christianity was, charitably speaking, highly idiosyncratic. Where his wisdom lies is that he knew this was the case. He never stopped looking for reality, knowing that “For now we see through a glass darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known” (1 Corinthians 13:12).

Philip K. Dick also never stopped asking, What constitutes the authentic human being? This is a question we all must ask if we are to live as free persons oriented toward the good. Whatever perils or promises are realized should the metaverse emerge from the world of imagination into our reality—be they sinister, pathetic, or simply banal—each of us must make it a virtual vocation to discern the truth above mere appearances and ubiquitous fictions. Dick, himself so often bedeviled by these questions, saw reason for hope in people’s capacity to do so:

The power of spurious realities battering at us today—these deliberately manufactured fakes never penetrate to the heart of true human beings. I watch the children watching TV and at first I am afraid of what they are being taught, and then I realize, They can’t be corrupted or destroyed. They watch, they listen, they understand, and, then, where and when it is necessary, they reject. There is something enormously powerful in a child’s ability to withstand the fraudulent. A child has the clearest eye, the steadiest hand. The hucksters, the promoters, are appealing for the allegiance of these small people in vain. True, the cereal companies may be able to market huge quantities of junk breakfasts; the hamburger and hot dog chains may sell endless numbers of unreal fast-food items to the children, but the deep heart beats firmly, unreached and unreasoned with. A child of today can detect a lie quicker than the wisest adult of two decades ago. When I want to know what is true, I ask my children. They do not ask me; I turn to them.

Idols for Destruction

The first commandment given to Moses on Mount Sinai was “Thou shalt have no other Gods.” In his Small Catechism, Martin Luther gave a concise explanation for this commandment, stating simply: “We should fear, love, and trust in God above all things.” Science fiction writers explore alternate realities in the realm of the imagination but rarely trust them. Faith placed in the metaverse to emancipate us from the constraints of creation and providence is a faith misplaced, one built on the shifting sand of the whims and capacities of those who fashion them. Looking to the metaverse for love, community, and solidarity outside our service to neighbors in the real world violates our duty to both them and their Creator. To fear the metaverse is also wrong, as God provides all we need even in this oversaturated information age. Philip K. Dick famously defined reality as “that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” The ultimate reality, God himself, is with us always, “And the Lord, he it is that doth go before thee; he will be with thee, he will not fail thee, neither forsake thee: fear not, neither be dismayed” (Deuteronomy 31:8).