A day doesn’t go by without some new story on the subject of technology, whether from the “this technology will solve all our problems” camp to the “robot overlords are at the gates” perspective. The debate surrounding the good and evil resulting from technological innovation has been taking place for millennia, but due to the ubiquitous nature of modern media, it seems somehow both more invasive on one hand and simply the water in which we swim on the other. How should we interpret all this information? What sources bring clarity and discernment? Or should we just “turn on, tune in, drop out”? While that phrase was made popular by counterculture icon Timothy Leary 55 years ago, it was actually coined by one of the most important prophets of the electronic age, Canadian professor Marshall McLuhan, an enigmatic provocateur whose religious sensibilities, though hidden from plain view, fueled his probing of this indomitable subject.

We need not be held captive by our tech if we take the time to understand it and how it has the capacity to change us, often without our being aware it’s doing so.

By Nick Ripatrazone

(Fortress Press, 2022)

By A. Trevor Sutton and Brian Smith, M.D.

(Concordia Publishing House, 2021)

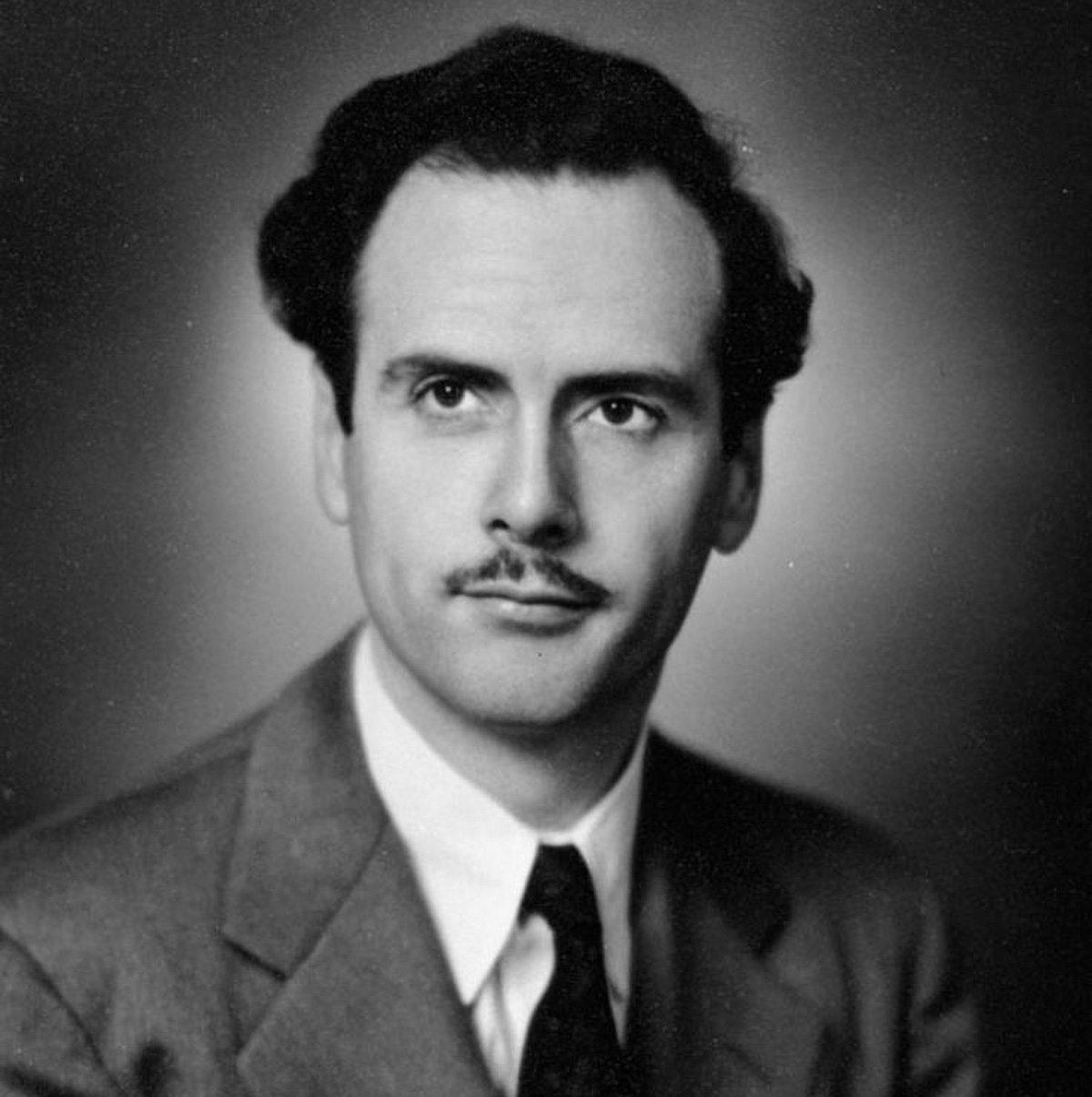

The profound cultural effect that McLuhan had from 1960 to 1970 cannot be overstated. Arguably the most influential critic of that age, McLuhan’s reach extended from the academy to titans of business all the way to Hollywood. His books were bestsellers, universities competed for his attention (Fordham University paid him $100,000 in 1967 to be a distinguished visiting professor, an amount that translates to more than $800,000 in 2022 dollars), and Woody Allen even cast him to play himself in the 1977 movie Annie Hall. While McLuhan is best known for his catchy and oftentimes confusing aphorisms—“the medium is the message,” the world as “global village,” the distinction between “hot and cool” forms of media—his deep study of literature and the classics gave him access to a stream of thought that revolutionized media theory for years to come, eventually turning it into a brand-new discipline called media ecology. To top it off, McLuhan is considered the patron saint of Wired magazine.

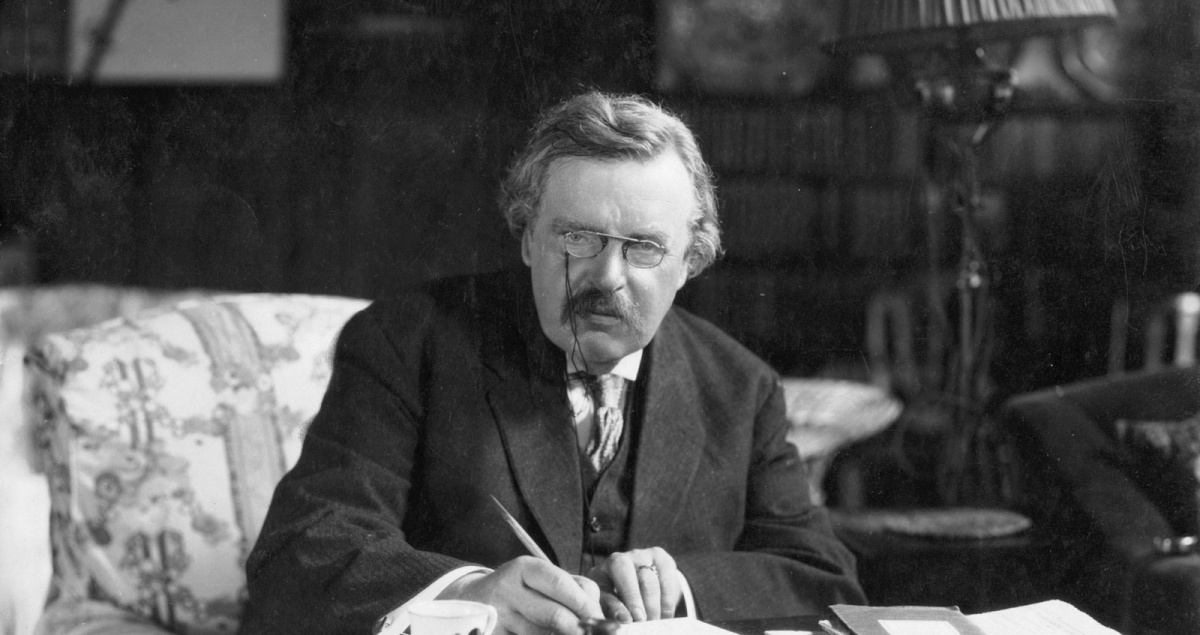

He was born in 1911 in Edmonton, Alberta, into a loving, cultured family. His father owned a real estate company and his mother was becoming an accomplished voice actress; in fact, young Marshall would sometimes accompany his mother on travels throughout Canada and the United States as she performed, memories of which he would draw on years later in his theories on oral communication. The family was loosely Protestant, influenced by both his father’s Methodism and his mother’s Baptist heritage. Marshall regularly attended Nassau Baptist Church while growing up, where Bible studies and Sunday school were a regular part of his education. Later in life he looked back on this stage in his religious development as being provincial and anti-intellectual. Stating that “I could never have respected a ‘religion’ that held reason and learning in contempt—witness the ‘education’ of our preachers. I have a taste for the intense cultivation of the Jesuit rather than the emotional orgies of an evangelist.” He enrolled at the University of Manitoba at 17 and shortly thereafter drifted toward agnosticism, even while continuing to read Shakespeare and the Bible each night before bed and journaling extensively about his religious thoughts. It was during his postgraduate study at Cambridge that he began to explore the writings of Catholic theologians, apologists, and poets such as Thomas Aquinas, G.K. Chesterton, Jacques Maritain, T.S. Eliot, and Gerard Manley Hopkins. These studies led him into a time of serious religious reflection, culminating in his being received into the Roman Catholic Church on March 24, 1937. Regarding Chesterton, McLuhan declared: “I know every word of him: he’s responsible for bringing me into the church.” It was Chesterton’s 1910 book, What’s Wrong with the World, that offered McLuhan a “template for how Catholicism could be both a religion and a cultural worldview.” While it is fairly well known that McLuhan was a dedicated Catholic, it is far less understood how his deep-seated religious beliefs influenced his public work. If you were to do a cursory overview of his books, interviews, and popular-level writings, it would be hard to determine whether religion had anything serious to contribute to his theories at all. Nick Ripatrazone’s book Digital Communion: Marshal McLuhan’s Spiritual Vision for a Virtual Age fills in that religion gap in McLuhan studies, offering a short but trenchant overview of how deeply McLuhan’s Catholic faith centered his thinking and was the ultimate foundation for the entirety of his work.

The Power of Television

Digital Communion opens with Pope Paul VI’s historic trip to the United States in October 1965. As the first pontiff to ever visit the Americas, his one-day tour of New York City was jam-packed: a meeting with President Lyndon B. Johnson, an address at the United Nations, and a visit to the World’s Fair. More than one million people crowded along the published route to see him wave from the back of a customized Lincoln Continental, and almost 90,000 people crowded into Yankee stadium to attend Mass. But perhaps the most memorable part of the pontiff’s visit was the unprecedented television coverage of his breezy, 14-hour tour. The major networks covered the entire affair without commercial interruption, and an estimated 100 million people watched in North America and nearly 200 million in Western Europe.

While it is fairly well known that McLuhan was a dedicated Catholic, it is far less understood how his deep-seated religious beliefs influenced his public work.

The significance of this event was momentous for several reasons and not simply for the political and theological narratives. Arguably more impactful was that it took place just 38 years after engineers at Bell Labs in Whippany, New Jersey, broadcast a short message from Herbert Hoover, then secretary of commerce, from Washington, D.C., via the nascent technology called “television,” to a group of influential business leaders in New York City. Hoover declared in his optimistic message that “all we can say today is that there has been created a marvelous agency for whatever use the future may find, with the full realization that every great and fundamental discovery of the past has been followed by use far beyond the vision of its creator.” The rapid acceleration of television’s use, and therefore power, was bound to change the world. Ripatrazone does a masterful job of fitting McLuhan into this well-told story of rapid technological innovation, as well as showing the importance of his love of the classics (his dissertation at Cambridge focused on the Latin triviumand essayist Thomas Nashe) and how his Catholic faith developed the foundation for his social criticism.

Along with Chesterton, the other main Catholic influences on McLuhan were James Joyce and Gerard Manley Hopkins. Regarding Joyce, it is said that McLuhan’s “study of media ‘began and remain[ed] rooted’ in the Irish novelist.” Joyce’s Ulysses and Finnegans Wake were particularly noteworthy in McLuhan’s literary development. An internationally respected communications scholar once cornered me at the 2019 annual Media Ecology Association meeting in Toronto when he found out I hadn’t read Finnegans Wake and proceeded to explain that there was no way I could understand McLuhan without first digesting Joyce’s eccentric novel. Ripatrazone spends an entire chapter arguing that, “in the end, what made Hopkins and Joyce especially apt for McLuhan was their Catholicism”—and reminding us that by 1962, nine out of 10 homes had a television, thus McLuhan, being “steeped in literary and religious history, steeled by faith, and charged with an open and omnivorous mind,” was ready to move front and center into the “electronic present.” It was the relatively quick conquest of television over older forms of media that drove McLuhan forward. “Television, like language, disrupts and then reconnects image and idea. Much like the stylistic lines and sentences of Gerard Manley Hopkins and James Joyce, television was a new form of communication.” And to McLuhan, any form of new communication was simply another “extension” of the human being. In other words, he “thought of a medium as an extension of the human body or the mind: clothing extends skin, housing extends the body’s heat-regulating mechanism. The stirrup, the bicycle, and the car are all extensions of the human foot.”

And these extensions always carry consequences. To the frustration of many, McLuhan saw himself as a generalist, able to explore multiple avenues and directions with “no commitment to any theory—my own or anyone else’s.… I just sit down and start to work. I grope, I listen, I test, I accept and discard; I try out different sequences—until tumblers fall and the doors spring open.” He felt the specialist merely “stake[s] out a tiny plot of study as his intellectual turf and is oblivious to everything else.” Given his generalist ideals, he was able to investigate any and all of emerging media’s after-effects. Recorded at the zenith of his career, McLuhan’s masterful interview with Eric Norden for Playboy magazine in March 1969 (available in a SFW PDF online) puts on display his often complex and wide-ranging ideas. Digital Communion is at its best when exposing these generalist tendencies that allowed McLuhan to explore, probe, and question all sorts of connections to media and our humanity, especially our religious sensibilities. Rarely is McLuhan explicit in this religious exploration, yet Ripatrazone points out that he nevertheless believed that the electronic world should be of concern to “every catechist and liturgist” and that the “Church has more at stake than anybody and should set up an institute of Perennial Contemporaryness!”

After McLuhan published his first book, The Mechanical Bride (1951), a series of critical essays on modern advertising, he rarely played the moralist. Rather than telling people what to think, he would state: “I have no point of view. I’m a person who swarms over a situation from all aspects simultaneously. I am a metaphysician of the media. That’s why I’m not interested in the moral issues.” I believe it’s such statements that lead many of McLuhan’s readers to miss the religious undertones in his writings. It is here that Ripatrazone’s research shines the brightest: unpacking the seeming contradiction between McLuhan’s own words regarding his having “no point of view” and books such as his seminal Understanding Media (1964), where he consistently used a religious vocabulary to explain the changes that electronic culture was having on modern man. It’s clear that McLuhan’s works “demand a high degree of participation and involvement from the reader. They are poetic and intuitive rather than logical and analytic.” But as Ripatrazone notes, McLuhan’s own books, lectures, and television appearances “consistently employed not only religious language and references but a religious sensibility: the Catholic and particularly Jesuit-influenced view that God exists in all things.”

Virtual Communion?

I found the first five chapters of Digital Communion to be a discerning mix of thoughtful research and helpful anecdotes, guiding the reader to a more nuanced and “thick” understanding of McLuhan’s extensive religious commitments. One area of departure, or rather underdeveloped thought, was the book’s conclusion. Here the author tries to apply a McLuhanesque critique to the COVID “moment” we’ve been living in for the past two years. As a practicing Catholic, Ripatrazone delves into the conflict that the pandemic created for churches as they increasingly moved to online services, including streamed Masses. One of the main questions parishes across the country wrestled with is: Can Holy Communion, a very physical act and the embodiment of Christ’s work on the cross, be taken virtually? Anticipating some of these conversations 20 years ago, the Catholic Church created the Pontifical Council for Social Communications, which concluded that “virtual communion is unable to capture ‘the incarnational reality of the sacraments and liturgy’ … there are no sacraments on the Internet; and even the religious experiences possible there by the grace of God are insufficient apart from real-world interaction with other persons of faith.” Catholics aren’t alone in this struggle. Earlier this year, an online firestorm ensued after Anglican priest Tish Harrison Warren wrote a January 30, 2022, New York Times editorial titled “Why Churches Should Drop Their Online Services.” Her article generated thousands of responses from Protestant circles, many of them negative. These types of questions are not easily answered, especially in an age of ever-expanding technological innovation. The speed at which change is happening outpaces the time it takes to contemplate these types of questions in any meaningful way.

Along with Chesterton, the other main Catholic influences on McLuhan were James Joyce and Gerard Manley Hopkins.

So was McLuhan merely an observer or truly a critic? Ripatrazone closes with the idea that

it is precisely because McLuhan’s theories were so centrally Catholic and yet doctrinally undetectable to many that he is the perfect model for a spiritual understanding of the virtual world. While more cynical critics might think McLuhan’s method was a form of obfuscation, it is better to consider that McLuhan’s Christian vision so fully formed his worldview that there was no need to outline the foundational theologies or doctrines that structured his assumptions. McLuhan’s role was not to be an evangelist; it was to describe the changing world that he occupied and to inevitably do so as a Christian. In a secular world, that itself is significant.

Or put another way: He that hath ears to hear, let him hear.

Developing Healthy Habits

While for many readers, especially Christians, McLuhan might be too covert in his cultural/religious critique of media, there are many other books to choose from that dive right into clear theological reflection when it comes to technological themes. In fact, a quick Amazon search will give you dozens of options in this vein. One of the newer additions on the market that takes a decidedly overt stab at engaging modern technological questions from a generally Christian and, in this case, specifically Lutheran point of view is Redeeming Technology: A Christian Approach to Healthy Digital Habitsby A. Trevor Sutton and Brian Smith, M.D. The blurb on the back cover permits no misunderstanding as it describes the book as offering “biblical wisdom with mental health guidance to help you rethink your technology use from a Christian perspective.” The authors even include discussion questions and a “Do This, Not That” section after each chapter to offer practical action steps. This style is broadly considered to be in the religious self-help genre, created specifically to be clear, thoughtful, and immediately usable. That being said, the authors pack a lot of research into this relatively short, engaging book.

In the opening chapter, after reminding us that we check our phones nearly 100 times a day, the authors explain why they wrote the book: “As a psychiatrist and a pastor, we have observed countless examples of unhealthy, out-of-balance, and idolatrous worship of technology. As practitioners—one specializing in mental health, the other specializing in spiritual health—we are concerned about the powerful influence that modern technology has on individuals, families, communities, and society as a whole.” The pastoral and mental health aims of the book are personal and clearly tied to their vocations. Together, the authors have seen lives devastated by technology through addiction, poor choices, and myriad other factors. Therefore their project is holistic in nature as they seek to “consider how technology negatively and positively impacts the whole person—the spirit, soul, and body.”

One clear strength of Redeeming Technology is the amount of data the authors deploy, even if briefly, to discuss and bolster their arguments. The footnotes and statistics allow for a reader to access quality sources if they want to explore the topic more on their own. Also, another general strength, especially given the target audience, is the number of biblical references and amount of theological insight woven into the distinct argument of the book. Broken into 10 succinct chapters, the authors take a survey approach to many complex topics within the field of technology and media studies. Using Jonathan Swift’s classic satire Gulliver’s Travels as a springboard, the authors explore the full, and often unrecognized, extent to which technology has influenced our everyday existence.

Redeeming Technology lists a range of astonishing facts about the ever-increasing rates and types of modern technological consumption that should make any thoughtful reader ask, Why are we doing this to ourselves? That being said, the authors explain that the biblical language of redemption (thus the title of the book) offers hope when confronting even the most insidious types of captivity. I’ve already alluded to the distinction between how McLuhan approached a very similar topic and how Sutton and Smith approach it: They root their approach in theological language from the very start, stating, “Before we can use technology like Christians, we must talk about technology like Christians.” After briefly unpacking what is commonly known as the doctrine of creation, the idea that God spoke the world and everything in it into existence and declared it good, the authors show how “God charged His human creatures with the task of making new things and living creative lives.” Exploring the world and creating things is literally part of our design. Tension clearly enters this narrative when one considers the Christian knowledge of sin. As created beings marred by sin, we have the propensity to use our creative gifts for evil purposes. Using the creator/creature distinction, the authors remind us that “as creatures, we can easily confuse creation with the Creator and thereby ask too much of that which is created.” And this approach commonly leads to idolatry, worshiping the created thing rather that the Creator.

Tech Neutrality?

It is with this basic theological foundation that they join the crowded conversation taking place all around us regarding the positive and negative aspects of technology. Is technology good or bad—or simply neutral? This is one of the core questions at the heart of technology studies. If tools are intrinsically neutral, are they then rendered good or bad in how they are used? Quoting Langdon Winner, the authors prompt us to consider that “all tools and technologies have been designed to predispose us toward certain patterns, behaviors, and consequences.” It is in this same vein that I am reminded of the Italian social theorist Paul Virilio’s profound point that “when you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck; when you invent the plane you also invent the plane crash … and when you invent electricity, you invent electrocution.… Every technology carries its own negativity, which is invented at the same time as technical progress.” The clear and necessary reminder in this section of the book should not go unheeded. Many people trumpet the overwhelming good that technology has done for the world, and while undoubtedly true, many of those same cheerleaders forget that every single technological “advance” has a tradeoff, an opportunity cost, or simply put, a negative consequence. The authors point to multiple examples of modern “creators” who ended up ruing their creation given the unforeseen, and often deleterious, ways their ideas ended up affecting society.

Why is this so easy to forget? One main reason could be the speed at which technology is progressing. In 2016 the World Economic Forum issued a statement describing the defining features of the Fourth Industrial Revolution: “There are three reasons why today’s transformations represent not merely a prolongation of the Third Industrial Revolution but rather the arrival of a Fourth and distinct one: velocity, scope, and systems impact. The speed of current breakthroughs has no historical precedent. When compared with previous industrial revolutions, the Fourth is evolving at an exponential rather than a linear pace. Moreover, it is disrupting almost every industry in every country. And the breadth and depth of these changes herald the transformation of entire systems of production, management, and governance.” The digital era is a breakneck fusion of technologies that is increasingly blurring the lines between the physical, the digital, and the biological spheres. The futurist Roy Amara would often say that “we tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.” This pronouncement is becoming more prescient by the day and, if true, it’s logical to conclude that there isn’t a single person or sphere of life and culture that isn’t being molded right now to fit these new patterns of life.

Redeeming Technology’s chapter on beauty offers an antidote to these disconcerting questions and highlights the co-authors’ different strengths. You can see the pastoral mind at work when discussing the theological dimensions to beauty in contrast to the psychological effects of social media on modern conceptions of beauty. I found one of the more profound points in the book to be the focus on Josef Pieper’s concept of visual noise. The German philosopher died in 1997 but was very forward thinking when it came to how screens affect our common humanity. In his book Only the Lover Sings, “Pieper argued that rather than help us see and perceive more, televisions and screens blunt our ability to see. He wasn’t suggesting that our physiological eyesight changes; rather, we begin to lose our ability to observe God’s creation and perceive reality, both spiritually and physically.” Pieper, ever concerned about our ability to live lives that reflect what is true, good, and beautiful, offers a poignant observation that, left unheeded, will surely be to our detriment.

Their project is holistic in nature as they seek to “consider how technology negatively and positively impacts the whole person—the spirit, soul, and body.”

Work and Calling

My one main critique might be minor if not ironic for a book with a Lutheran viewpoint. Near the conclusion, the authors include a short primer on Luther’s understanding of vocation and how it might be applied to the cultural moment. While the basic introduction to the theme is fine, the authors fall flat in application to the zeitgeist. Over the past 30 years, there has been an abundance of books, conferences, seminars, and institutes generated in the Protestant world attempting to define and encourage a more holistic understanding of calling and vocation. While this movement has done much to expand the definition of vocation, many of the teachings do little to consider the societal framework in which the individuals in their audiences exist. In other words, it is the aforementioned intense, systemic pace of change that is rendering these primarily individualistic teachings unhelpful. The French Christian theorist Jacques Ellul (whom the authors mention briefly) foresaw this temptation in the early 1970s and offers a critique of this truncated understanding of vocation in his provocative article “Work and Calling.” According to Ellul: “Work such as it is today cannot be universally upheld as a calling. At best, let us say that God can by grace and miracle cause work to be lived by man as a gift and a calling. Nonetheless, the theological rapport between vocation and work has been broken: work as such is not vocation, not a calling.” Ellul goes on to argue that raw technique and efficiency has taken over every profession (even the pastorate), so finding true “calling” in one’s work is virtually impossible. More work needs to be done here to reconcile Luther’s view and what is actually happening due to societal change.

All that being said, this book is definitely worth your time, ideally in a small-group format that welcomes sincere discussion. Redeeming Technology is a concise but amazingly diverse treatment of literary, biblical, and social themes that ultimately remind us that God and his world should be at the center of our lives, not our technologies.