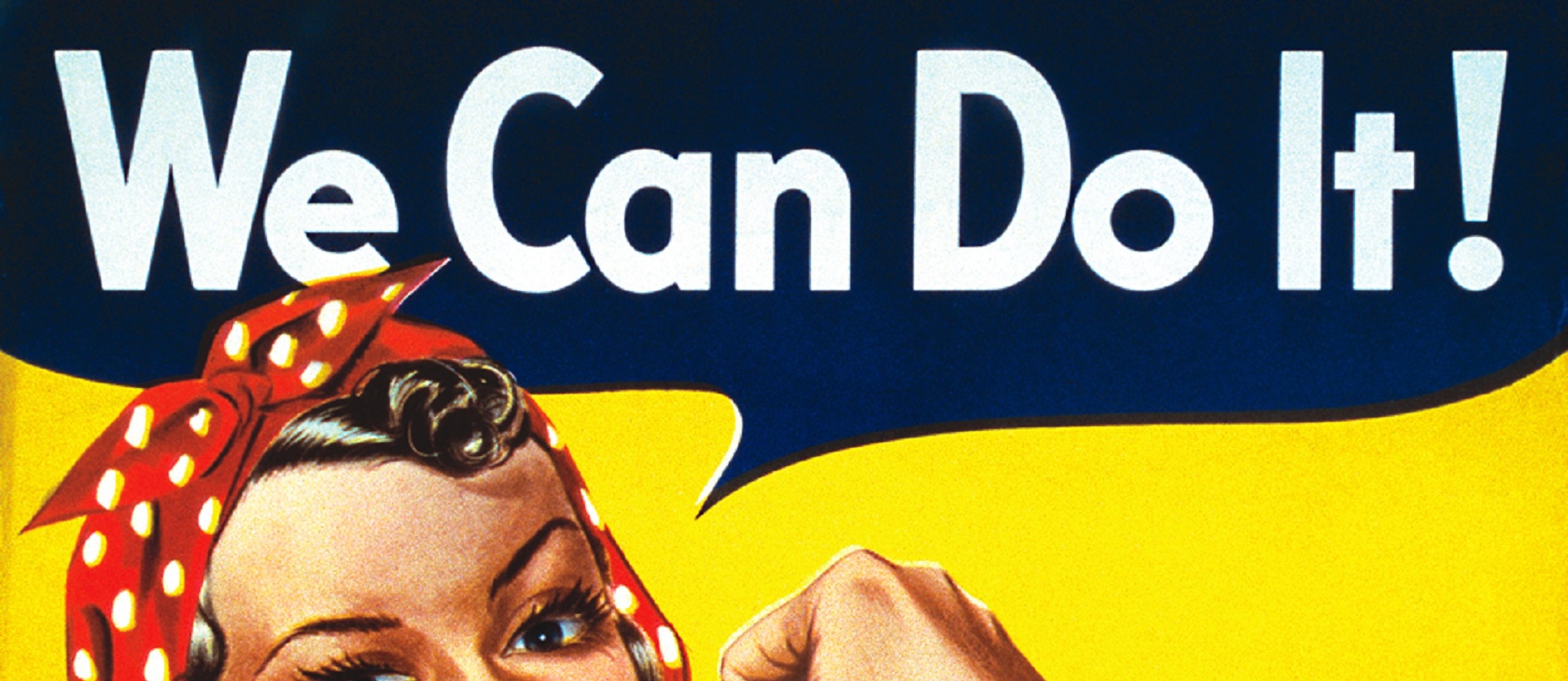

Women are called to the workplace, so how do we make it work? An interview with Katelyn Beaty.

Where are the resources for Christian women called to the workplace? Why isn’t there a larger discussion in churches about the life experiences of women? Asking these questions led Katelyn Beaty to write A Woman’s Place: A Christian Vision for Your Calling in the Office, the Home and the World (Simon & Schuster 2016). Beaty was the first female and youngest managing editor of Christianity Today and the cofounder of the blog Her.meneutics. She discussed several of the overall themes in her book with Religion & Liberty’s Sarah Stanley. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Religion & Liberty: How do you define “feminism”?

Beaty: Historically the first wave of feminism in the early 20th Century was really about women’s full participation in the political sphere. It was centered on giving women the right to vote. A lot of the women who were early champions of women’s voting rights were actually Christian, who wanted to see women have more influence on social issues of the day. So recognizing that women often had a reforming influence, they were concerned about alcohol abuse and the way that prisoners were treated, what was happening in schools and the abuses of factories that were employing young children.

Those early women of the feminist movement were really motivated by wanting women to have more of a reforming influence on society. The second wave of feminism, which most people take as a whole of feminism, was really centered on giving women greater power in the workplace and in institutions. It was also very much connected to the sexual revolution of the 1960s and ‘70s. So the second-wave feminists believed that women should have as much sexual freedom as men. And so they tended to be advocates of birth control. And of course that’s connected to the reproductive rights and the legalization of abortion. When Christians think of feminism, I think that’s the movement that they tend to think of.

There have been efforts made to integrate mainstream feminism with Christianity. I think you can make the case that there are aspects of feminist ideas that can be connected to what the Bible says about dignity of women and women bearing the image of God and being owed honor and worth and dignity. And that’s different from saying that there are no differences between men and women. I am thankful, as an evangelical Christian, for the fact that as a young girl, I could ask, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” and that there were options. It was accepted that I would work and have a profession. And I think we can thank our feminist forbearers for the work they did to advocate for women in the workplace even if they advocated for other ideas and movements we may find destructive. So I’m thankful for aspects of feminism. I am not ready to throw out the baby with the bathwater, but there are also aspects of feminism that are obviously very concerning and may have created problems for Western culture in the past 50 years.

How do you define “work”?

I define work by going back to the Genesis narrative. We read that God put Adam and Eve in the garden to keep and tend it; to work the soil and to really bring about abundance and order and beauty to the garden. Work, at its most basic definition, is what happens when humans interact with the created order to bring about something that wasn’t there before. That’s a really broad definition, but that would include work that’s done without pay, in the privacy of one’s home. For example: when you’re making a meal, when you’re tending your own garden, when you’re changing a diaper. You’re interacting with created goods in order to tend and keep them for the sake of other people.

In the book, I give this example of a feast that a friend and I put together in 2010. We invited a dozen people over, and we had multicourses of all sorts of Mediterranean food, and it was just a beautiful evening. That, I would say, was us working. That was us putting our hands to raw creative good to bring about something that wasn’t there before. By comparison, I talk about Café 180, which is a pay-what-youcan restaurant in a lower-income neighborhood in Denver, where Kathy Matthews, the founder, has created a restaurant model where people can come and enjoy fresh and healthy food and are asked to pay what they can. If you can’t pay anything, then you work for an hour or something doing dishes to earn your meal. But the restaurant brings together people from different backgrounds, different neighborhoods, to share a meal together. The fact that she has created this restaurant and this business is an example of how her work can reach far more people and have far greater systemic effects at good transformation than my friend’s and my meal. Those are examples of work.

But the point of the book is to call women to the second kind of work. Because I believe our institutions need women in positions of influence and leadership. And I believe women are called to participate in those institutions.

Your book and the issues addressed in it are often listed as “women’s issues” and sidelined into pink sections of bookstores and blogs. Ultimately this is really a human issue. How do we bring these issues to the mainstream?

I will say I have been really encouraged by the number of men who have read my book and have appreciated and resonated with it. And what I hear from those men many times is that the issues I’m writing about (such as greater representation in the workplace or work/life balance or, you know, flex time or paid parental leave) are issues that directly affect the women in their lives, whether their wives or their daughters or their coworkers. Simply by account of men being in relationships with women, men are called to hear and listen to the concerns of women when it comes to work and vocation.

When you look at the local church, every church is composed of at least 50 percent women. If you’re a pastor, it’s within your responsibility and care, simply as a discipleship issue, to concern yourself with the questions that women are asking and thinking about. If these are the questions and concerns that half of my congregation is bringing to the table, then I really need to understand them. And ultimately, I think, advocate for them in some way. Advocate doesn’t necessarily mean the pastor needs to go speak to a boss and advocate for equal pay but, rather, think about how the local church supports women who are wading into these questions of work and vocation.

Say a woman has just had a baby and is going back to work full time. Is she going to find support or encouragement at the local church level? If a woman in your church has experienced gender discrimination in the workplace, is there a space at the local church for her to share that concern and find support? At the local church level, I would just love to see women’s issues stop being relegated to the pink section.

Women are human, and yet I think the way we disciple women in the local church sometimes suggests that women are these fundamentally different kinds of things from men. I believe what women and men share in common is far greater than what separates them or what makes them unique. So if we believe women are human, then women’s issues need to be the conversation of all people in the church.

Would you explain the Industrial Revolution’s impact and influence on creating separate male and female “work?”

For most of human history, relatively speaking, the locus of industry was either at home or closely connected to home. The Industrial Revolution essentially took work outside of the home. It moved the locus of work from the home to the factory or to the business. With that, it separated men and women. So husbands and wives, who would have been working together on the farm, were now separated with the husband going to work in the factory for 12 hours a day to make a wage and the woman managing the responsibilities at home. That’s why we have this divide.

When we talk about work/life balance and the difficulty of balancing work and life, we are really reflecting the legacy of the Industrial Revolution. The Industrial Revolution and the technological advances of the last 100 years have taken a lot of the creative and time-consuming work of the home outside of the home. The work of managing a home became much less taxing and time consuming, especially in the 20th century. Because of that you have advertisers and businesses praising the housewife. She can cook and clean, but it all takes very little time. What does she do during all this free time? We don’t know. But the point is that the interesting work of the home has been replaced by machines, whether outside or inside of the home. And so the work of managing the home has ultimately become, for a lot of women, less interesting. That’s why you have the women of the mid-20th century saying, “I’m actually really bored at home.” We can’t blame these women for wanting to enter the workforce outside the home because they want the good fulfillment of meaningful work that is really connected to our bearing the image of God.

What do you see for the future of the faith-and-work movement?

I think most leaders in the faith-and-work movement recognize that if the movement is going to have long-lasting effects in the church, then it needs to become more diverse in a few different ways. So more ethnically diverse and speaking to the concerns of leaders of color and persons of color in the church. Connected to that, becoming more socioeconomically diverse. One potential pitfall of the faith-and-work movement is to set up white-collar jobs as being more important or holier than working-class or blue-collar jobs. That denigrates the importance of manual labor.

I actually see much more interest in faith-and-work leaders in honoring the dignity of manual labor and wanting to avoid the suggestion that meaningful work only includes things like founding a company that has a social good component. For example, working in an investment firm where all of the money is invested in social good. Anything with a social good component. These are jobs that simply aren’t available to most people. We want to avoid the impression that only those jobs are the ones that have an element of importance or meaning for our society.

I think there is also a gender imbalance. There just aren’t that many women leaders in the faith-and-work movement. There are certainly some, but this tends to be a male-led movement. I think incorporating the experiences of more women will go a long way for this movement because the reality is that more and more women are working outside the home. We can’t assume that if you’re a Christian woman, you will work for maybe some time after college, but then you’ll drop out of the workforce as soon as you have a family. Women are simply going to be in the workforce for a lot longer than previous generations of women. They will certainly need the same faith-and-work resources as their male counterparts.