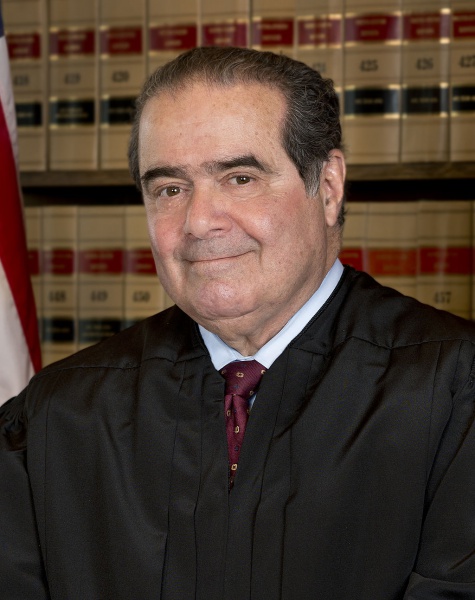

For the seventh Acton Institute Annual Dinner on June 17, 1997, Justice Antonin Scalia gave the evening’s keynote lecture. Despite having spoken these words nearly two decades ago, the message is just as important today as it was that evening. The following essay has been transcribed and excerpted from that speech. The full audio is available online on Acton’s PowerBlog. In honor of the late justice’s significant promotion of freedom and virtue, he is also featured in this issue’s "In the Liberal Tradition.”

I want to talk about the Constitution of the United States, something to which I devote a fair amount of my time these days. There is really nothing like it in the world. It is not a great constitution simply because it’s our Constitution. Never again in the history of mankind will a governing document be put together by political parties figuring out how to passel out the power the best way. It will never happen again. From mid-May to mid-September, the most respected and politically experienced people in the nation spent every day of the week in Philadelphia. That’s a whole baseball season. You know that it would not happen that way again today. The great men and women would go up to Philadelphia and they would adopt some general principles and say, “Let the staff work out the details,” and they’d go back to Washington.

I’m a textualist and an originalist. I do not believe that its meaning evolves over generations so that to each age it contains everything that’s good and true and beautiful, even though it’s not really written in there. My philosophy was, until recently, not only not weird, it was orthodoxy. Everybody at least said that the Constitution was that rock, that unchanging, fundamental document that means today what it meant yesterday. And it’s our salvation. Now they didn’t always follow it. It isn’t that you didn’t have willful judges who would twist and distort it in the past. But the difference was in the good ol’ days they had the decency to lie about it. They would say, “You know, it used to mean that but ...” That was a lie. Hypocrisy is the beginning of virtue. Today you do not have to lie about it. You just simply say, “Well, it ought to mean that. And therefore it means that.” We indeed have opinions. It is a development that has occurred probably in the last 35 years or so in American constitutional jurisprudence. So that something that was not cruel and unusual punishment then may be cruel and unusual today because it evolves. Our opinions say, “To reflect the evolving standards of decency of a maturing society.” That’s the language in our opinions. Let me say it again, “The evolving standards of decency ...” It is so Pollyannaish. “Every day in every way we get better and better. Societies only mature. They never rot.” Now, that is, of course, not the frame of mind of a group of men who think there is a need for a Bill of Rights. They are less Pollyannaish. They have less confidence that humanity will be better or even, indeed, as good in the future as it is today. I mean, surely the whole purpose of a Bill of Rights is precisely to stabilize certain provisions so that they cannot be changed by a future and less virtuous generation. That’s the kind of frame of mind they have. And that frame of mind is reflected in my kind of constitution, but it is not reflected in the Constitution that we have today and that most lawyers, most judges, and, worst of all, I’m afraid, most Americans believe in. And many of you probably believe in it, although you don’t know it. That is, you have heard the phrase “the living Constitution.” That wonderful document that grows with the society that it governs so that it always reflects the best virtues of that society. It’s a tough thing to argue against. I am trying to sell you a dead Constitution, right? You’re at a disadvantage right away.

When I was a kid growing up in New York City, in Queens, it was simpler. When people got frustrated with the state of affairs in the world or in government, they would pound the table and say, “There ought to be a law.” A good, healthy democratic reaction, I thought. What they now say is, “It’s unconstitutional!” I mean, if there is anything that really is bad it must be unconstitutional. Never mind the text. It doesn’t matter. The text is irrelevant. We’ve got a due process clause; we’ll squeeze it in there somewhere. But if it’s really bad, it has to be unconstitutional. To take another example from popular culture, there was a while back an ad on television for some pizza sauce. I think it was Prego pizza sauce. The husband in this ad, he asks his wife, “You’re going to buy this store-boughten sauce? Does it have oregano in it?” She says, “It’s in there!” He says, “Yeah, but does it have pepper ...?” “It’s in there!” “Does it have ...?” “It’s in there!” “What about basil?” “It’s in there!” We’ve got that kind of a constitution now. What do you want? You want a right to an abortion? It’s in there! You want a right to die? It’s in there! Whatever is good and true and beautiful. Never mind the text. It’s irrelevant.

Another problem with rejecting textualism and originalism. This is really the killer argument. It’s a terrible thing to do, but ask the law professor on the other side, “Ok, suppose I agree with you, that originalism is not the proper method of interpretation. We’ll use your method of interpretation. What is your criterion?” Profound silence. There is not even another candidate in the field. It is not enough to be a non-originalist, to say, “You know, I don’t believe that what governs us is the original meaning of the text.” That just means you don’t agree with me. If you’re not an originalist, you’ve got to be something else. What is your theory of interpretation if it is not originalism? Non-originalism is not a theory. And, you know, once you ask for that, you’ll get as many different criteria as there are law professors. The philosophy of Plato? The philosophy of John Rawls? Natural law? You either use originalism or you use nothing, which is—those areas where we’ve made up the Constitution—essentially what we use. There is no criterion. If you want your judges to just vote with their guts, fine. Originalists don’t always agree. Clarence Thomas is an originalist. We will disagree as to what the original meaning was now and then. But we know what we’re looking for anyway.

I will conclude on the unhappy note that unless we turn back from this approach to the Constitution, I really think we will destroy the republic or destroy the value of a written Constitution and a written Bill of Rights. Because ultimately, if the Constitution does not bear a fixed meaning that can be figured out by lawyers, then its meaning will be determined by who do you think? The majority. I mean, the people have come to figure out that I don’t know anything any more about whether there’s a right to or whether there ought to be a right to die than they know. I mean, I don’t know any more than Joe Six-Pack. This is not a lawyer’s question. The people have come to figure that out. And when they come to figure that out, they also figure out that they should select their Supreme Court justices not on the basis of whether these people are good lawyers. Because they’re not doing lawyers’ work anymore. They should rather select them on the basis of whether they agree with them on whether there ought to be a right to this, that and the other thing. And that is what our confirmation hearings have deteriorated to. If that is what the Supreme Court is doing, that is what those hearings ought to be like. It’s inevitable though; the people will take that back to themselves. And it is the people whom the senators represent in those hearings. And they will ask one nominee after the other, “Do you think there is a right to this in the Constitution?” And he says, “I don’t think ...” “You don’t think there is one? Why? I certainly think there is, and my constituents think there is. And if you don’t think that right is not in that Constitution, I’m certainly not going to vote to confirm you. Now, what about this other right? Do you think that’s ... ?” He’s just really quite, quite mad. Conducting a mini plebiscite on the meaning of the Constitution of the United States every time you select a new Supreme Court justice. But it will inevitably be that way, and it ought to be that way. If the Supreme Court is not doing the work of lawyers, which is doing the work of taking a text and interpreting it the way lawyers interpret text to discern what was its original meaning. So I am not at all hopeful that it’s possible to get back to where we were. Really. It is such an alluring, enticing philosophy to believe that the Constitution means whatever you think it ought to mean. How do you talk somebody out of that? It’s a wonderful, wonderful thing. And judges who are non-originalists, who think the Constitution means what it ought to mean, they go home happy every night.

Really. They never make a decision they don’t like.

I make a lot of constitutional decisions I don’t like. I was the fifth vote in the flagburning case because I am a strict constructionist. My reading of the First Amendment is that it protects freedom of expression. If you interpret the First Amendment literally, “This Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech or of the press.” Well, I guess handwritten letters are neither speech nor press, so the government ought to be able to censor handwritten letters, right? Of course not. That’s strict construction, but it’s silly construction. You don’t interpret a text that way. I interpret the First Amendment, when it says “speech and press,” it is using the figure of speech called synecdoche. You name a part to represent the whole, as in, “I see a sail.” Speech and press represent expression. That’s the way I read the First Amendment. So I said, “If somebody burns his own flag, it’s his flag. He’s doing it to show contempt for the government, contempt, even, for the flag. He’s entitled to express contempt for the flag.” I was the fifth vote. It didn’t make me happy. I do not like, I used to say, bearded people who go around burning flags. I came down to breakfast the next day and my wife, the lovely Maureen, who, you know, has a sharp Irish tongue, is standing at the stove humming “Stars and Stripes Forever.”

You don’t have to put up with that kind of stuff if you’re not an originalist, because the Constitution means what you want it to mean. It’s wonderful. It’s very hard to talk people back out of it. I’ve tried to talk you back out of it tonight. I hope you will try to talk your friends back out of it. And you don’t have to call it a dead Constitution. Let’s call it the enduring Constitution.