In most Roman Catholic parishes in Poland, during the Mass on July 30 the priest read a pastoral letter calling on the government to increase the price and restrict the sale of alcohol. Written by Bishop Tadeusz Bronakowski, the president of the Polish Bishops Conference’s Apostolate of Sobriety, it rightly noted that alcoholism is responsible for such national epidemics as “domestic violence, car accidents caused by drunk drivers, irreversible birth defects of children whose mothers drank alcohol during pregnancy, deaths caused by alcohol abuse, rape, divorce,” and damaging young people in numerous ways. Among other solutions, he called on politicians to restrict the “physical and economic availability” of alcoholic beverages.

The call for state economic intervention against alcoholism is rising across Europe. But is a “sin tax” the right answer?

Alcoholism casts a shadow over Poland and the EU

The letter was read as Polish Catholics usher in a month of abstinence. The Roman Catholic Church has encouraged Catholics to voluntarily refrain from drinking alcohol, or reduce their consumption, every August since 1984. August was chosen, because it is a month of several Marian feasts – including Saint Mary of Chęstochowa, St. Mary of the Angels, and the Assumption of Virgin Mary – as well as significant historical events in the life of the nation, like the miraculous victory over the Bolsheviks in the Battle of Warsaw on August 15, 1920, and the beginning of the Warsaw Uprising on August 1, 1944.

The call for state interventionism against alcoholism is rising across Europe. But is a “sin tax” the right answer?

Alcohol abuse, hardly a new problem among Europeans, is increasingly becoming a topic of public debate. The average European consumption of alcohol per capita (among those aged 15 or older) is 12.5 in liters of pure alcohol. Polish alcohol consumption, while higher than average, is in line with many former Soviet countries – and lower than Portugal – but significantly higher than the Italians, Macedonians, or the Dutch.

Government policy had one effect: Beer sales overtook spirits in the late 1990s, a change commonly attributed to the fact that beer is the only alcoholic beverage that may be legally publicized (although under significant restrictions). Beer is now the most popular form of alcohol in Poland, accounting for 55 percent of all alcohol consumption. But total alcohol consumption has remained static, even risen, with the switch to the lower alcohol content beer displacing spirits.

Nonetheless, alcoholism remains a problem in Poland, as it is elsewhere in Europe. According to the World Health Organization, the rate of “hazardous drinking” in Central and Eastern Europe (2.9) and Nordic countries (2.8) is nearly three-times that of Southern Europe (1.1). And the amount of alcohol Poles are drinking is increasing by the year.

Clearly, the bishops are right to sound an alarm about this worsening problem. But, when it comes to economics and public policy, we must diligently ask whether they have considered all the potential impacts of their proposals.

The problem with the “sin tax”

Bishop Bronakowski’s pastoral letter outlines what it perceives as the “responsibility” of state and local authorities. “The great responsibility of the state is not only to make wise and precise law but also effective and ruthless enforcement,” he wrote. “You must completely ban the advertising of alcohol and limit its physical and economic availability.” That echoes a report from the Polish Parliament’s Bureau of Analysis on “Alcohol in Poland,” which says, “One of the main factors that influence the amount of consumption of alcohol is its accessibility, both economical and physical.”

The idea that state price controls and state monopoly over liquor sales may help reduce alcohol consumption is quite common across the old continent. “Political action like minimum pricing and reducing access to alcohol needs to be taken now” across Europe “to prevent many future casualties,” said Markus Peck, chairman of the department of gastroenterology and hepatology, endocrinology, and nephrology at the Klinikum Klagenfurt Hospital in Austria.

The impetus for action is clear and commendable. However, the specific call for state action ignores several key facts about “sin taxes.”

Although we all agree with Bishop Bronakowski that alcohol abuse is a severe problem, both in Poland and in the rest of Europe, the governmental and economic actions that he proposes may cause even deeper problems. “The consequences of the sin tax are often the very opposite of those intended by its designers,” as Fr. Robert Sirico has written. The correlation between regulations on selling alcoholic beverages and consumption of alcohol in different European countries is disputed. Finland is moving toward liberalization of its alcohol market. On the other hand, Italy despite its relatively light regulation of alcohol, has one of the lowest rates of alcohol consumption in Europe.

As with any policy, there are unintended consequences to a sin tax. Scandinavian countries impose strong limits on alcohol sales, including a state monopoly and controlled (read: artificially higher) prices. Sweden and Finland, as a result, have to face the problem of considerable smuggling from other countries within the Schengen Area. The state-run stores, which hold a monopoly on alcohol sales, keep short working hours in order to limit consumption. Instead, this encourages consumers to stock up, often buying more alcohol than they had intended. Having the extra alcohol on the premises itself may encourage binge drinking.

Poland, which borders seven different countries including three non-EU states, is especially susceptible to smuggled contraband. Lower prices have already created a large smuggling operation of illegal cigarettes into Poland. Higher prices on alcohol will almost certainly increase alcohol smuggling. In addition to the criminal element, the quality of the smuggled alcohol may present health issues of its own.

Spiritual weapons, in the hands of loving families and strong intermediary institutions, will doubtlessly prove more powerful than relying on state limitations, monopoly enterprises, and economic interventionism.

In addition to contraband, we should expect that increasing prices on vodka will increase the clandestine home production of alcohol. Such consumption is already an issue. Poland increased the excise tax on alcohol by 15 percent in 2014, which caused the growth of the black market. It is improbable that Poles, who learned how to survive years of shortages of many products during the Communist era, will change their habits according to state limitations.

Who benefits from the sin tax?

Another problem linked to the so-called “sin tax” is who benefits the most from it. The taxes imposed on any kind of good increase the state budget. This gives rise to the paradox that the state profits from a higher consumption of alcohol. In 2014, the excise tax on alcohol added 10 billion zlotys ($2.8 billion U.S.) to the Polish budget, not including the income from the VAT tax on alcohol sales. It becomes obvious that the government’s budget relies on the taxation of these products. Why would it then be interested in diminishing sales? Has the state ever been interested in reducing its own budget?

The tax also harms the legitimate economy. Limiting the “physical accessibility” of alcohol, by banishing it from store shelves and selling it only at stores in the state-run monopoly, will cause the closure of many small businesses and increase unemployment. Similarly, the “sin tax” collected is often not used to fight alcoholism (or lung cancer, etc.). Instead, politicians find other uses for the funds, increasing the size and scope of government and harming the market environment even more.

What attitude should the Church take?

The undeniable problem of excessive drinking in various European countries leads the Church authorities to propose measures to protect the families and individuals from negative consequences of alcoholism. In his letter, Bishop Bronakowski rightly said that alcoholism is not just a problem of single persons but of the whole national community. However, in this delicate problem prudence is highly recommended. Any kind of government interventionism into the economy brings unintended consequences, which inflict different – something more intense – pains.

Thankfully, his pastoral letter enumerated the responsibilities of three different areas: the responsibility of the family and the Church, as well as the responsibility of the public authorities. As he observed, the most fundamental force against addiction is a community of strong families teaching responsibility in a loving environment. The role of the Church is then to strengthen and protect those families and to cooperate with them in the formation (including the education) of children into responsible and mature adults. Its key function, he wrote, consists in “pointing out the true meaning of life and by leading people to God.” He praised pastors who barred alcohol from church functions and who started groups that help people overcome alcoholism. “Let us become the hands of merciful God,” he concluded.

Jesus said that, when it comes to certain kinds of evils, they are “not cast out but by prayer and fasting” (St. Matthew 17:18-21, Douay-Rheims). These spiritual weapons, in the hands of loving families and strong intermediary institutions, will doubtlessly prove more powerful than relying on state limitations, monopoly enterprises, and economic interventionism.

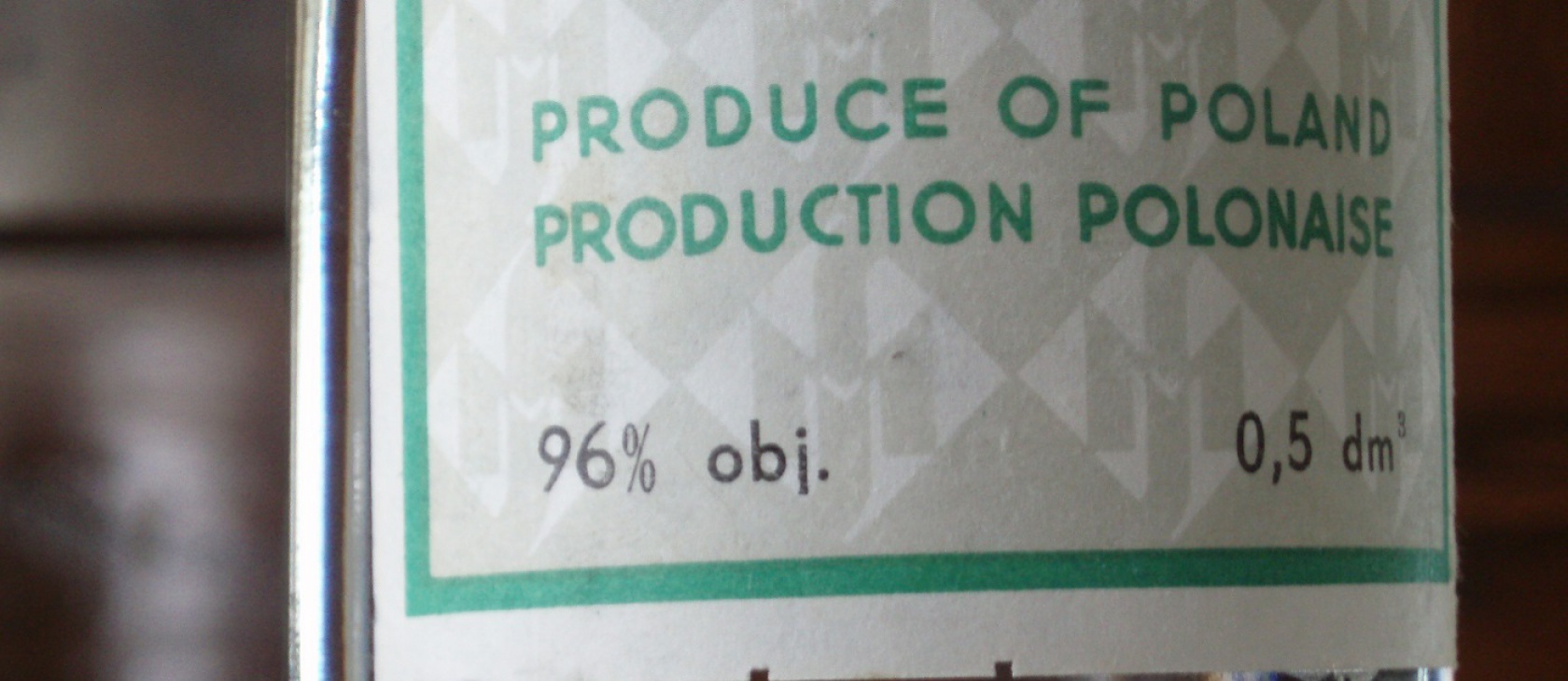

(Photo credit: Eddie~S. This photo has been cropped. CC BY 2.0.)