The Bolshevik Revolution was one of the epochal events of modern history, continuing to affect the world in which we live 28 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Modern governments and systems of economics were created in imitation, or opposition, of its fundamental tenets. Too much of the international commemoration of its centenary last week consisted of celebration by its intellectual heirs. However, lovers of liberty across the transatlantic sphere also paused to reflect upon the occasion.

On October 27, supporters of a free society in the Netherlands (who call themselves “liberals”) held one such event titled, “The Russian Revolution then and now.“ Its emcee was Patrick Van Schie, director of the Telders Foundation, a Dutch free market-oriented think tank that co-hosted the event with the VVD-Thematic Network International and the European Liberal Forum.

“You might wonder why liberal organizations are commemorating the Russian Revolution,” he said. “Our answer then is threefold.”

The first reason, he said, is that “the communist power grab in Petrograd and consolidation of Lenin's regime in Russia marked the realization of a liberal dystopia. Communism is in every respect the opposite of what liberals strive for.”

“It stands," he said, "for:

- exulting the collective over the individual;

- dictatorship over democracy;

- censorship over free speech;

- state terror over civil rights and limited, accountable state power;

- a centrally planned economy over a free market-oriented economy.”

Secondly, we remember its significance for the way the West reacted - or failed to react - to Communism. “The survival of Lenin’s regime in Russia and its expansion to other countries after the Second World War - in Eastern Europe, east Asia, and Cuba - started a new phase in international relations. Without the October Revolution and its consequences, we have we would have never known the Cold War,” Van Schie said.

Americans understand the distortions that crept into American political and economic life as a result of the 44-year standoff. Rock-ribbed conservative politicians became willing to tolerate budget-busting levels of domestic spending in order to maintain an adequate Defense budget. President Reagan saw that the moribund Soviet economy would collapse from a robust arms race ... but high cumulative levels of deficit spending coupled with the historically low economic growth during the last administration have threatened to capsize the U.S. economy. The Cato Institute recently held a symposium on the degree to which the Bolshevik Revolution increased the size and scope of government in the West.

“The third reason for liberals to commemorate 1917,” Van Schie said, is “the lasting influence of the Russian Revolution on that country,” i.e., modern Russia. He asked, “Is the Putin regime some kind of revival of tsarism, a continuation of the Soviet Union (mind you, Putin made his career in the KGB!), or a combination of both?”

Polls show Josef Stalin remains popular, perhaps the most popular man in Russia. Modern Russia seeks to integrate the USSR’s status as a global superpower into its broader history, without grappling with the totalitarian oppression that accompanied it. Such a selective reading of history is untenable for any people and, as history has long shown, when people begin to pine for the glory days delivered by a previous dictator, the consequent suppression and denial of human rights temporarily refresh their memories about the true nature of authoritarianism.

The Telders Community has a write-up of the event, which included Sean McMeekin, author of The Russian Revolution: A New History; Koert Debeuf, director of The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP) Europe; and Tony van der Togt, a researcher at the Clingdael Institute. You may also enjoy Patrick Van Schie's column on the centenary of Communism and his review of McMeekin's book. (All links are in Dutch.)

The author is grateful to Patrick Van Schie for providing the notes of his talk for the composition of this article.

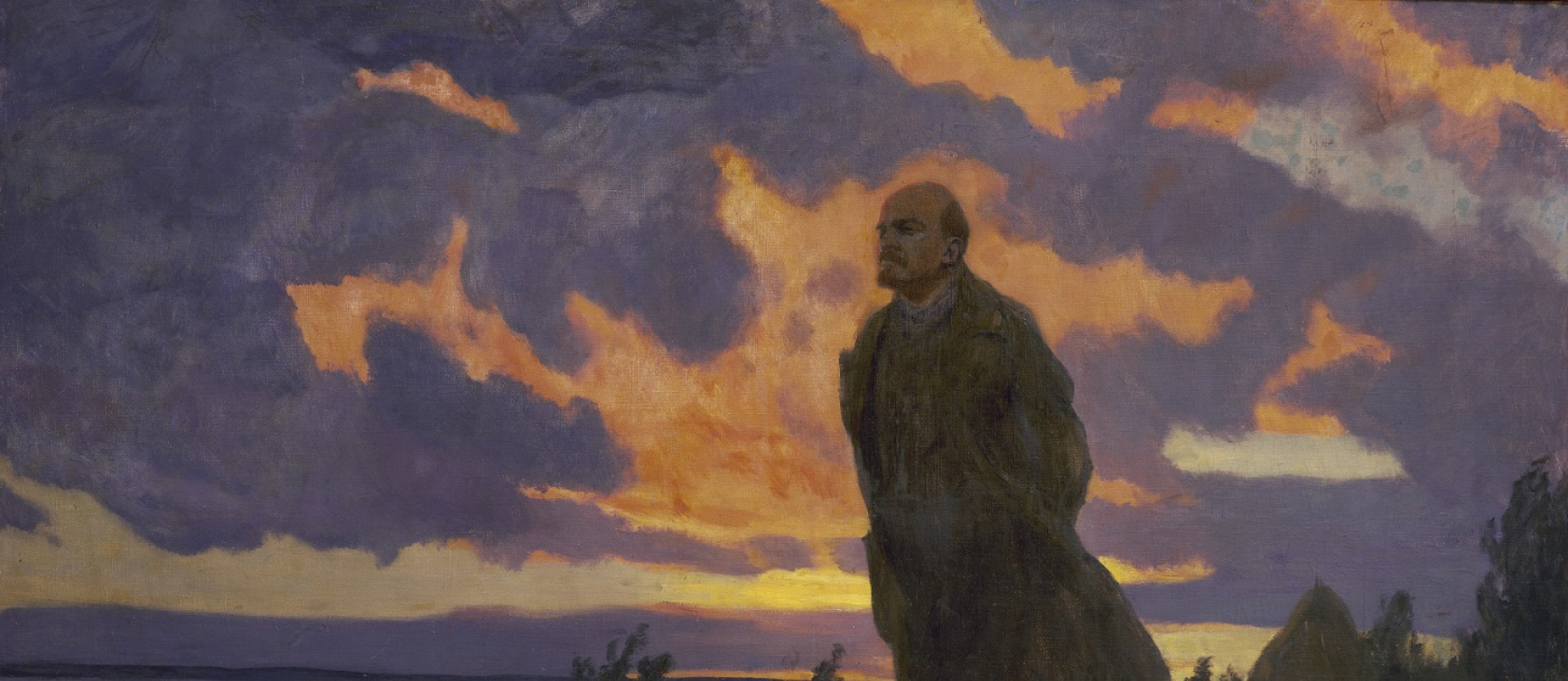

(Photo credit: Public domain.)