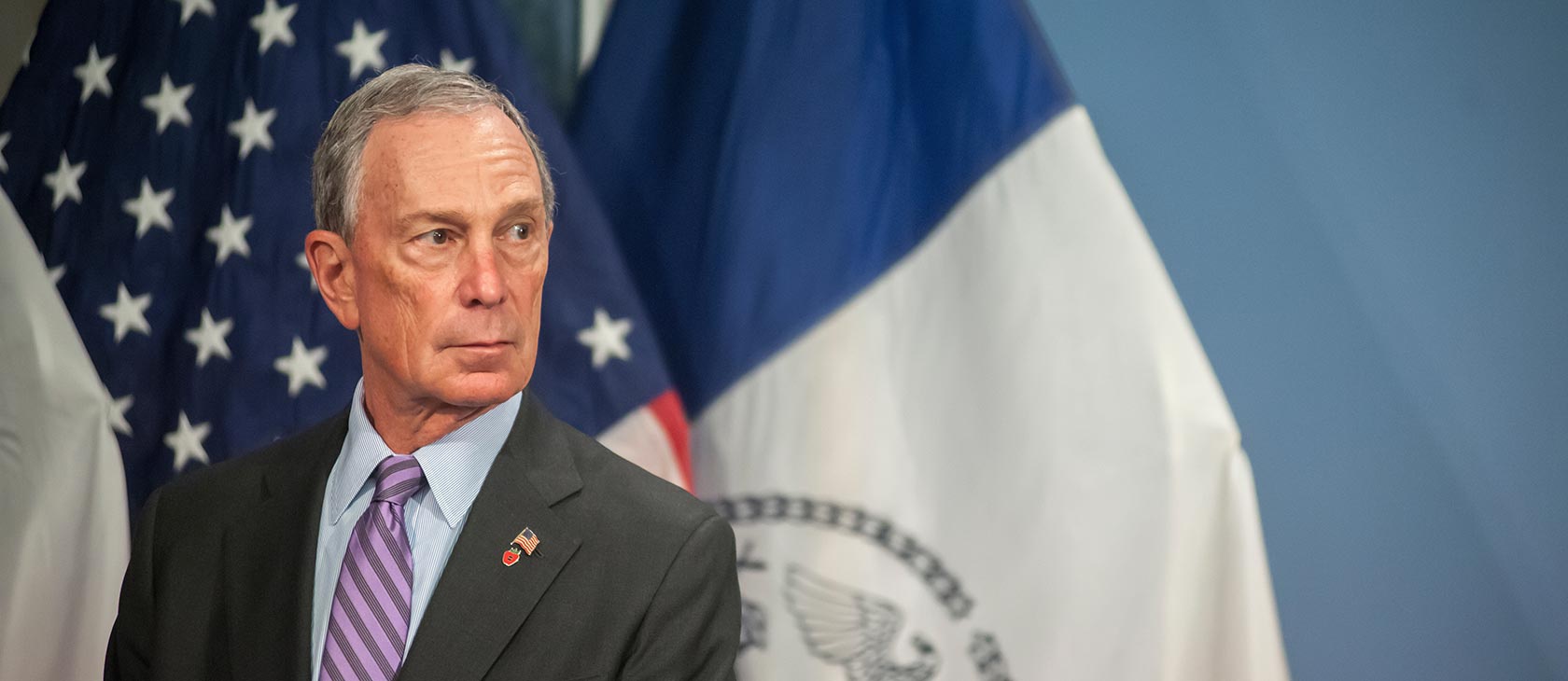

Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg's comments that farmers have little “gray matter” have rightly stirred controversy. However, in the justifiable backlash, people have overlooked another, equally concerning portion of his comments.

Video has resurfaced, as it has a habit of doing during elections, of Bloomberg discussing the progression of the economy from an ancient agricultural society, to the Industrial Revolution, to the burgeoning information economy. He began:

The agrarian society lasted 3,000 years, and we could teach processes. I could teach anybody, even people in this room – no offense intended – to be a farmer. It’s a process. You dig a hole; you put a seed in; you put dirt on top; add water; up comes the corn. You could learn that. Then we had 300 years of the industrial society. You put the piece of metal on the lathe; you turn the crank in the direction of the arrow; and you can have a job.

Bloomberg contrasted these forms of economic life with the information economy, which “is fundamentally different.” Learning “how to think and analyze” requires “a different skill set,” he said. “You have to have a lot more gray matter.”

For their part, farmers reply that modern agriculture is an information-driven industry involving the use of sensors to assure the seed achieves proper soil penetration, GPS-guided farm equipment, and – yes – the legal know-how to sort through a myriad of federal regulations. This, they say, requires at least as much “gray matter” as working for Enron or Lehman Brothers.

To the extent that the comments imply a lack of intelligence, they are right to be upset. Bloomberg's campaign team has said the mayor was addressing ancient farming, not modern techniques. This brings us to the troubling aspect of his speech.

Delusions of competence give politicians the confidence to issue a torrent of regulations so complete that they drown those with real-world experience.

The concerning words Michael Bloomberg uttered, which have gone unremarked, are: “I could teach anybody … to be a farmer.” Whether in the ancient world or the present, Bloomberg – who, it may be safely discerned, is unacquainted with the working end of a hoe – would be ill-equipped to teach anyone the secrets of the agricultural trade. Delusions of competence give politicians the confidence to issue a torrent of regulations so complete that they drown those with real-world experience.

Even the mayor's description of how the ancients grew crops missed multiple interstitial steps known to prehistoric tribes. In addition to planting and watering, farming involved such fundamentals as soil preparation, weeding, and pest control. The Mishnah discusses methods of soil cultivation and regeneration (Shevi'it 3). Genetic modification of sweet potatoes began no later than 8,000 years ago in Peru, around the same time European farmers started fertilizing their crops. Improving the soil created a “long-term relationship with the land” that “fostered notions of land ownership,” according to Science magazine. The emergence of the capitalist system of free enterprise, markets, and exchange – which evolved into the information economy, and made Bloomberg a multibillionaire – came about because agriculture was emphatically not merely a process.

Indeed, one could well argue agriculture is less skilled now than in the pre-industrial world, when all the functions now accomplished by high-tech machinery had to be understood and executed by the farmer himself. This gave him what Michael Crawford called “craft knowledge,” a deep understanding of the nature of the materials of his profession “acquired through disciplined perception.” This non-credentialed mastery developed from regarding the creation, in the words of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, as a gift “to increase and to develop with respect and in harmony, following its rhythms and logic in accordance with God’s plan.”

Let's assume that Mayor Bloomberg mastered this process. How would he know to plant corn rather than soybeans, wheat, rice, or apple trees? The information necessary to know which crops to plant does not belong to any one individual, F.A. Hayek reminded us. “Economics has from its origins been concerned with how an extended order of human interaction comes into existence through a process of variation, winnowing, and sifting far surpassing our vision or our capacity to design,” he wrote in The Fatal Conceit. He continued:

Modern economics explains how such an extended order can come into being, and how it itself constitutes an information-gathering process, able to call up, and to put to use, widely dispersed information that no central planning agency, let alone any individual, could know as a whole, possess or control. Man's knowledge, as [Adam] Smith knew, is dispersed. As he wrote, “What is the species of domestic industry his capital can employ, and of which the produce is likely to be of the greatest value, every individual, it is evident, in his local situation,judges much better than any statesman or lawgiver can do for him.” Or as an acute economic thinker of the nineteenth century put it, economic enterprise requires “minute knowledge of a thousand particulars which will be learnt by nobody but him who has an interest in knowing them.” Information-gathering institutions such as the market enable us to use such dispersed and unsurveyable knowledge to form super-individual patterns.

When politicians assume this knowledge, they presume to dictate the means and ends of human creative activity. “In managerial economy, the regulation of production will not be left to the ‘'automatic' functioning of the market, but will be carried out deliberately and consciously by groups of men, by the appropriate institutions of the unlimited managerial state,” wrote James Burnham in The Managerial Revolution. “Under the centralized economic structure of managerial society, regulation (planning) is a matter of course.” Often, the object of their regulation becomes the individual's private life – from how much soda to drink in one sitting, to the proper sodium level of food donations to the homeless, to the proper volume of earbuds.

The Nanny State notion that the state has the correct answer for every citizen, in every case, becomes genuinely destructive when applied to business. Bloomberg, whose eponymous news service publishes valuable and perceptive financial information, has a greater understanding of trade and markets than many others in the presidential race. He, and all his competitors, must learn that regulation destroys wealth, stifles economic growth, and substitutes the voice of the regulators for the “rhythms and logic” infused into all creation by divine providence.