The current student loan crisis is a perfect, yet dismal example of policy gone wrong. It is right and good to desire the best life for our children, and for some that includes a traditional four-year undergraduate degree. But in recent years this has been upheld as the essential golden ticket for a prosperous and successful life, deemed necessary to the American Dream. Policies built on myths and fallacies can destroy an economy and, in the process, harm the very people they intend to help.

College attendance rates have skyrocketed in the U.S. since 1965, from just under six million students to just under 20 million. The biggest growth in attendance is at public universities, which account for almost three-quarters of all college students. In that same time period, the number of students who graduate with four-year degrees has increased significantly.

On their face, these data are encouraging: More people desire a college degree, and more are receiving it. However, 57 percent of college graduates leave college with an average debt load of $29,000. The average cost of attending an in-state university, including room and board, has increased by almost 50 percent since the year 2000. According to data from the New York Federal Reserve Board, total student loan debt reached $1.5 trillion in 2018.

When the myth of college-or-failure pervades society, it causes systematic disruptions.

The benefits of college attendance are empirically demonstrated. College graduates tend to have higher overall earnings than students without college degrees and are less likely to live in poverty. But there are several nuances we must understand. Not all students need to go to college to earn high salaries and live productive lives. When the myth of college-or-failure pervades society, it causes systematic disruptions. If everyone believes he or she must attend college, then some who otherwise would not pursue college do. The consequences are that it takes longer for those students to complete a degree. We now measure college completion rates in six years rather than four, and dropout rates are higher than they otherwise would be. The overall national six-year completion rate for the 2012 cohort was 58 percent – up slightly from previous years.

If you believe that you must attend college to be successful in life, but college is not the right fit for you, attending college and dropping out is worse than not going at all. This is especially true if you take on debt to attend college for a few years and then never finish. This adds to the $1.5 trillion in total student loan debt. Prudent debt can be important for people and businesses to create greater future productivity, but this debt does not signify a more productive future for college dropouts. The secret to a growing income is increased specialization, but there is more than one way to get this as a young person charting his or her future.

Vocational schools and trade schools are important opportunities for those who want to work in crafts and trades, and attendance in trade schools is on the rise. They can be completed in shorter time, outside formal college settings through apprenticeships and technical schools, and are less likely to saddle a 22-year-old graduate with oppressive debt. Some of the salaries in construction and trade work rival or exceed those of fields requiring a college degree. In 2018, the median pay for elevator installers and repairers was almost $80,000; it was $55,000 for electricians. Moreover, both sectors, along with other trade and craft sectors, anticipate job growth into the future. Job growth means a demand for skills and the promise of future income gains, and that is the security that everyone desires.

The myth of the perfect education (traditionally a four-year college degree) has led us down an unsustainable track. The huge burden of debt and the lessening value of the college degree creates uncertainty. The proper response to this is to destroy the myth that everyone needs to attend traditional college, and to work with students in middle and high school to help them figure out their skills – to walk with them through their future goals and desires, and to steer them towards those outcomes.

For those who want to attend traditional college, the future remains uncertain. College is increasingly expensive, with less bang for the buck. Colleges work hard to lure students with fancy gyms and water parks rather than lowering the professor to student ratio so the education itself will be better. For example, Texas Tech University boasts a water park with a 25-person hot tub, a water slide, and a lazy river, all for the price of $8.4 million. In many schools the dorms rival upper middle class suburban kitchens, with stainless steel appliances and granite countertops. While these are nice, and things to aspire to in life because you earn an income reflective of your increased productivity, it is difficult to argue that this is what makes a college degree worthwhile.

Government subsidies in higher education guarantee today’s realities: degrees that are more expensive over time and, in many cases, less valuable.

The essential problem of student loan debt and high tuition fees is not the loans themselves, but the skyrocketing costs that are due to heavy government interference in higher education. In a pure market, yes, you might see some schools with water parks and high-tech gyms, but you would also see lower-cost alternatives and colleges that specialize in the degrees themselves, rather than the environment in which those degrees are pursued. Competition in the supply of college education would also guarantee more options for everyone – Ivy League, community colleges, large schools, small schools, and more online alternatives. But the competition required to obtain this reality does not exist today. Government subsidies in higher education guarantee today’s realities: degrees that are more expensive over time and, in many cases, less valuable.

The reality of this situation is grim, in that it is not just a financial problem; it is an egalitarian problem. Government intervention in higher education has truncated this “market,” making it not resemble much of a market at all. The consequence is that the rich can overcome this in a way that those in the bottom income quintiles cannot. And, while financial literacy may solve some of this by encouraging those who cannot afford college not to attend, the bigger problem lies at the root of this sluggish, crony system.

Senator Elizabeth Warren rightly worries about this and is using higher education reform as a key issue in her bid for the Democratic presidential nomination. However, her solution of cancelling debt to the tune of $640 billion will exacerbate the problem rather than fix it. We would all love for someone to sweep in and cancel our debt. That surely would make debt holders richer. However, the unintended consequence is that it will encourage even more students to take on unproductive student loans, and it will encourage more students to attend college who otherwise would not go. Finally, it will exacerbate the water park problem.

The real problem can only be solved by the necessary cultural shift away from the everyone-needs-to-attend- college myth and by inducing greater competition into the sluggish and opaque “market” of higher education.

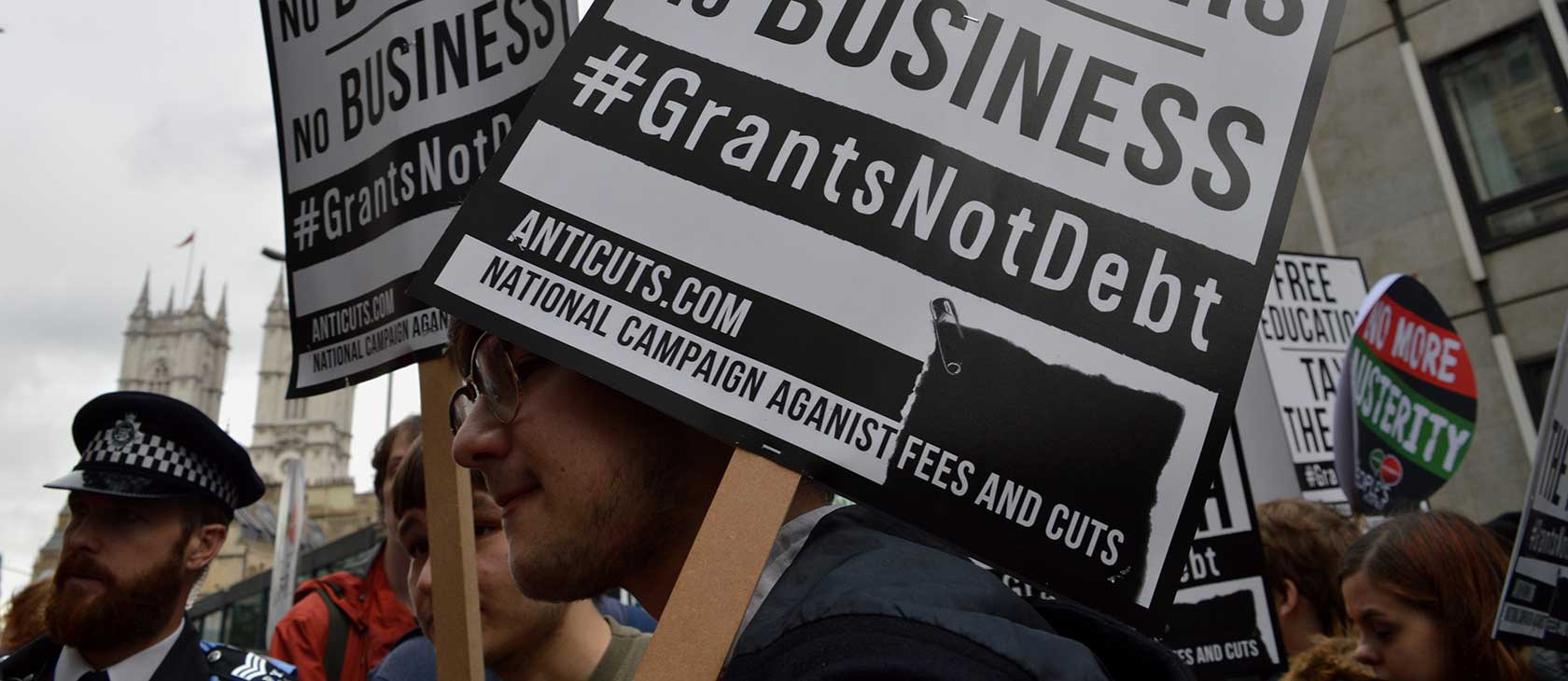

Featured image credit: Katherine Da Silva / Shutterstock.com. Editorial use only.