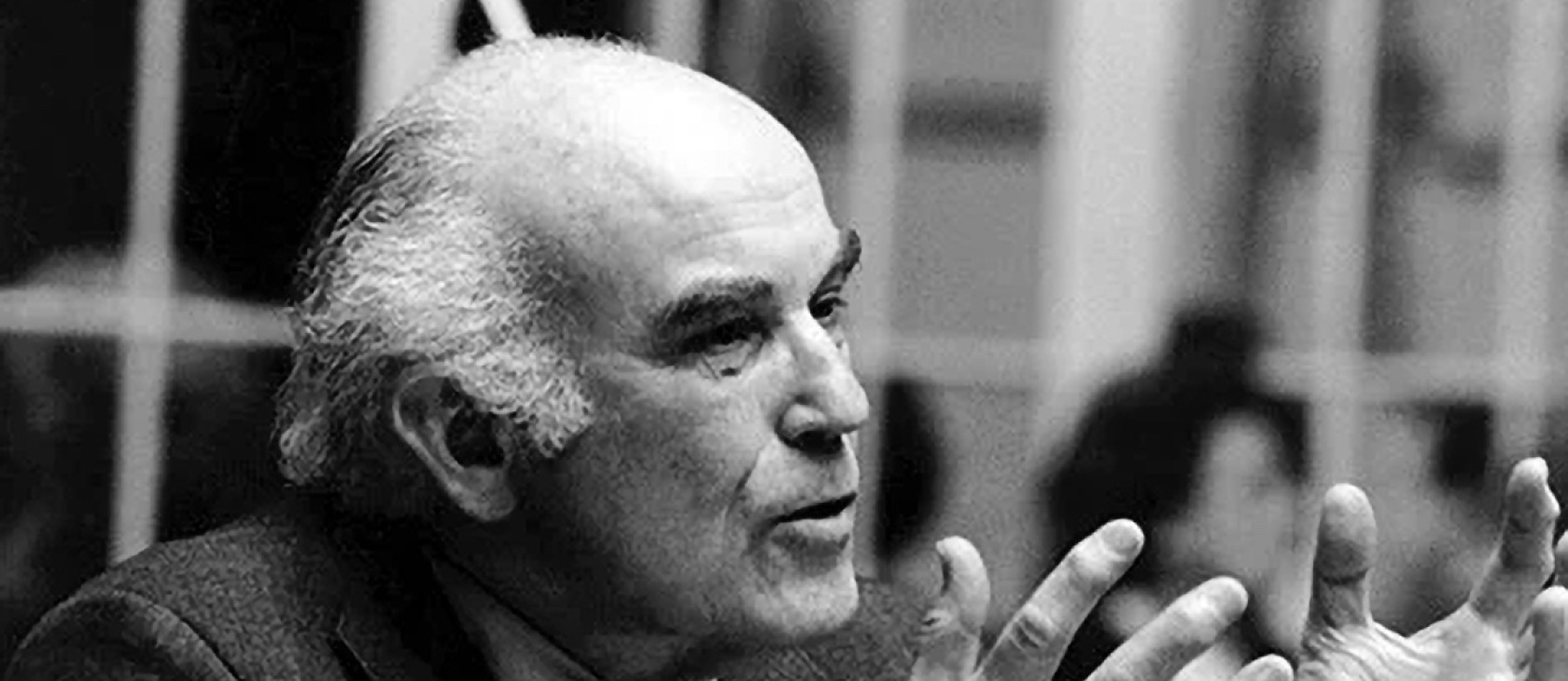

“To the contemporary social scientist,” observed Robert Nisbet (1913–1996), “to be labeled a conservative is more often to be damned than praised.” Already evident when he published it in 1952, Nisbet’s comment is even more accurate today. Surveys from the past decade have found that close to two thirds of undergraduate faculty call themselves far left or liberal, compared to about 13% who identify as conservative or far right. The disproportion is more pronounced at elite universities and in particular fields.

Both then and now, protests against these conditions tend to focus on political consequences, including accusations that students are subject to indoctrination. For Nisbet, the principal danger of marginalizing conservative thinkers and ideas was primarily intellectual. The modern study of human behavior is built on distinctive concepts, including status, norm, symbol, ritual. And these concepts—without which the disciplines of sociology, anthropology, and social psychology are hardly conceivable—emerged from a largely European tradition of conservatism that American scholars barely recognized, even for purposes of dismissal.

Nisbet’s mission was to revive that tradition. He did not expect that his efforts would directly contribute to electoral or policy victories by the organized conservative movement, with which he had a close but sometimes tense relationship. He did hope to combat what he called “the degradation of the academic dogma,” or the rejection of the principle that teachers and scholars should pursue knowledge for its own sake.

Nisbet was born in Los Angeles but raised mostly in the oil town of Maricopa, which he described as a “hostile challenge to the human spirit.” He found Macon, Georgia, where his paternal grandparents lived and his family briefly moved, more congenial. Prefiguring his conservatism, Nisbet admired the Deep South as an American bastion of personal (as opposed to legal) authority and traditional community. He later recounted that the Southern Agrarian manifesto I’ll Take My Stand made a deep impression on him, although he still considered himself on the left when it appeared in 1930.

After completing high school, Nisbet enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley. Except for a stint of military service during World War II, he would remain at Berkeley as an undergraduate, graduate, student, and professor until 1953 and in the University of California system as an administrator until 1972.

Although Nisbet moved on to other institutions, these California affiliations are not just a biographical detail. For Nisbet, “Old Berkeley” was the very model of a modern university. Free from the social ambitions that dominated famous East Coast colleges and publicly funded with a minimum of oversight, students and faculty at Cal were free to devote themselves to learning—as well as to recreation in a shabby but convivial environment that Nisbet affectionately recalled. If every conservatism is rooted in some sense of loss, Nisbet’s version was driven partly by his belief that this academic utopia had been undermined by the imposition of alien military, economic, and eventually ideological imperatives.

Nisbet’s education at Berkeley was dominated by the influence of Frederick J. Teggart, a former historian turned professor of “social institutions” who advised his doctoral thesis on “The Social Group in French Thought” in 1939. With Teggart’s encouragement, Nisbet argued that figures including Joseph de Maistre and Louis de Bonald represented a sort of “reactionary enlightenment” that exposed the true basis of human society in relations among religious, kin, and other groups rather than the abstracted individual.

Many of the themes that emerged more clearly in Nisbet’s 1953 masterpiece, The Quest for Community, were already present in his dissertation. Missing in the earlier work are thinkers who, Nisbet would come to believe, successfully mediated the abstraction of liberalism and the reactionaries’ authoritarianism. The dissertation says nothing of either Edmund Burke or Alexis de Tocqueville—at that time, an almost forgotten figure.

Tocqueville, especially, became key to the perspective Nisbet would dub conservative pluralism. A “monist” society was one that tried to enforce a uniform legal regime and pattern of life, usually by means of violent coercion. A “pluralist” society, by contrast, would permit different institutions and communities to pursue separate purposes in different ways, binding them together only when and as necessary to achieve truly shared purposes. The anomie or alienation famously diagnosed by Émile Durkheim, Nisbet argued in The Quest for Community, stems from the suppression of local, religious, or (in Europe) feudal orders with the pseudo-community of the nation-state.

Nisbet’s anti-statism was congenial to the nascent American conservative movement. Yet his suspicion of militarism and nationalism also offered a certain affinity to the New Left. Nisbet’s objection to the student radicals was not so much that they challenged U.S. foreign policy or the bland conformity of midcentury popular culture. It was that they did so in the name of further liberation of the individual. What was needed was not more personal independence with regard to sex, drug use, or other behaviors but a “new laissez faire” of groups, that allowed traditional institutions such as universities to select, cultivate, and, when necessary, discipline their own members. This was precisely the authority that the new student movements rejected.

By the 1970s, Nisbet saw few prospects for salutary pluralism. His later works revolve around themes of progress and decline. Western civilization was in a “twilight” phase, in which the capital accumulated in previous eras was expended without being replenished. Although he was a scathing critic of deterministic theories of historical change, Nisbet worried that waning confidence in the possibility of improvement was a social disaster. Since Americans were never characterized by a strong interest in the past, loss of faith in a better future left them even more disoriented and desperate for quick but illusory fixes.

Although he remained affiliated with conservative institutions and wrote for conservative publications, Nisbet did not exempt the conservative movement from his pessimistic analysis. Like his heroes Tocqueville and Durkheim, Nisbet respected the social and cultural achievements associated with religion, particularly the Roman Catholic Church. But he was dismayed by the Reagan-era religious right, which he saw as petty, vulgar, and bullying. Nisbet did not necessarily oppose school prayer, restrictions on abortion, or other policies favored by largely evangelical Christian conservatives. But he saw the attempt to impose them at the national level as an expression of the monism he rejected on the left.

When he died in 1993, Nisbet was more obscure than he’d been a few decades earlier. As with his contemporary Russell Kirk, Nisbet’s intellectual, impractical, vaguely European brand of conservatism had little natural audience among the American political class. Nisbet’s thought was more naturally at home in the universities he loved. By that time, however, the arguments he mounted and sources he revered were even less popular than at the beginning of his career. The cause was not limited to ideological imbalance. As Nisbet had warned for decades, the shift of professional incentives from undergraduate teaching to specialized research, and from curatorial to inquisitorial modes of scholarship, proved stifling to the academic imagination.

Yet Nisbet’s sociological diagnosis seems more relevant now than ever. For all the pathologies linked to social media and identity politics, it seems clear that they’re responses to the vacuum of community that Nisbet diagnosed many years ago. We must either find a way to channel unavoidable demands for meaning and belonging into families and other embodied communities that provide what Christopher Lasch called a “haven in a heartless world” or see them played out as escalating and counterproductive bids for centralized power. The task has only gotten harder since Nisbet described it in The Quest for Community. But it remains the central task of our twilight age.