Some reviews are difficult to write. Responding to David Hollinger’s Christianity’s American Fate, I initially used a tone that was wholly mocking and sarcastic, because the book is, from so many points of view, a dreadful piece of work. I backtracked on that somewhat because I genuinely respect the author’s earlier writings and, moreover, the present book has some portions that are really thoughtful, which I will certainly be citing in future. Please appreciate my dilemma when I say that Hollinger’s book is not as completely awful as it first appears.

David Hollinger is a scholar of note, but his most recent contribution to the discussion about evangelicalism in America betrays his political hobbyhorses more than insights into a diverse group of Christian believers.

By David A. Hollinger

(Princeton University Press, 2022)

Hollinger’s argument can be summarized thus. Donald Trump’s presidency, and the political movement associated with it, were and are a political, spiritual, and cultural catastrophe. Trump’s success was rooted in the support of religious conservatives, or as Hollinger mainly describes them, white evangelicals. Beyond falling prey to sinister political temptations, those believers frequently and consistently reject science and even objective reality:

Christianity has become an instrument for the most politically, culturally, and theologically reactionary Americans. White evangelical Protestants were an indispensable foundation for Donald Trump’s presidency and have become the core of the Republican Party’s electoral strength. They are the most conspicuous advocates of “Christian nationalism.” … Most of Christianity’s symbolic capital has been seized by a segment of the population committed to ideas about the Bible, the family, and civics that most other Americans reject.

The question, then, is how so many Americans became Marching Morons, which Hollinger helpfully expounds by contrast with mainline Protestants. He actually calls these mainliners “ecumenical” Protestants, a change that produces no obvious advantage. The deliberately retro term harks back to the ecumenical movement that was a hot button item for ecclesiastical bureaucrats a couple of generations ago.

“Ecumenical Protestants” benefited from their greater educational advantages, and the flourishing of universities in northern and midwestern states during the 19th century and after. At no stage does Hollinger seem to acknowledge the egregious class prejudice that permeates every word of his account of how us fine chaps achieved our present state of moral and intellectual perfection, while the peasants remained in the mire. Surely, those “ecumenicals” might object, our trust funds alone can’t account for the difference?

It is hard to know where to begin approaching this rant. One basic problem is that Hollinger not only does not define most key terms; he actively mocks attempts to do so. What, for instance, is an evangelical? There are actually some excellent attempts to do this, most famously by David Bebbington in the four points of his “quadrilateral”—conversionism, crucicentrism, activism, and biblicism. If the model is not perfect, it is very useful. It also clearly shows that the term evangelical is not affiliated with any political package or racial ideology. Historically, most black Protestant churches were, and are, thoroughly evangelical, and Latinos and Asian Protestants likewise. Hollinger quotes the quadrilateral, and then huffily declares

that this has some value for understanding the doctrinal history of at least part of evangelicalism across the centuries. But this sense of “true” evangelicalism elides the entire history of fundamentalist and evangelical connections with business-friendly individualism. Missing, too, from the quadrilateral is the vibrant tradition of premillennial dispensationalism, according to which evangelicals were encouraged to accept wildly implausible ideas, making QAnon’s theories seem less strange than they otherwise would be.

Where do you start? He takes a word that means something, then adds commentaries on some aspects of evangelical history (the business linkage) and asserts out of nowhere that they are the indispensable heart of the matter. He then suggests, simply wrongly, that premillennialism is a basic part of the evangelical message. It is for some but not for others. Throughout this book, Hollinger’s “evangelicals” should properly be understood as meaning “some right-wing activists affiliated with religion, with whom I disagree strongly, and you know them when you see them.” His argument proceeds from there, in perfect circularity.

Hollinger is also—shall we say, unintentionally—entertaining on the topic of conspiracy theories and the rejection of scientific consensus.

Millions of Americans believe patent falsehoods and live in epistemic enclosures that keep them from hearing even the most well-substantiated and carefully explained truths about vaccines, climate change, election outcomes, immigration, and a host of other matters of great public concern.

Note the dichotomy here. There are us normal people, Democrats and liberals, who accept the world as it is, as proven by objective expert science. Then there are far-right religious flakes.

As Hollinger almost says, “God, I thank thee, that I am not as other men are, or even as this Republican!”

But it is not hard to find many conspiracy theories espoused by liberals and the left, not to mention cases in which the same groups flout “well-substantiated and carefully explained truths.” QAnon has no monopoly on nonsense. Such instances reflect the sinister power of social media and the mob mentalities that they generate, for left and right alike. They are nothing to do with Christianity or with evangelical theology.

While on the subject of harmful mythologies, we might turn to Hollinger’s fundamental thesis that the Christian right, under whatever name, has seized “most of Christianity’s symbolic capital.” What does that actually mean? Who says? It is an excellent statement of the worldview of contemporary American left/liberals, who, whenever they see religion in public life, immediately think of the darkest stereotypes of far-right megachurch extremists. It has no necessary connection with the actual profile of U.S. Christianity, in which Roman Catholics remain the largest single contingent, nor does it address the many evangelicals and Pentecostals who are centrist or left in orientation. Who declared that those believers have suddenly forfeited their symbolic capital?

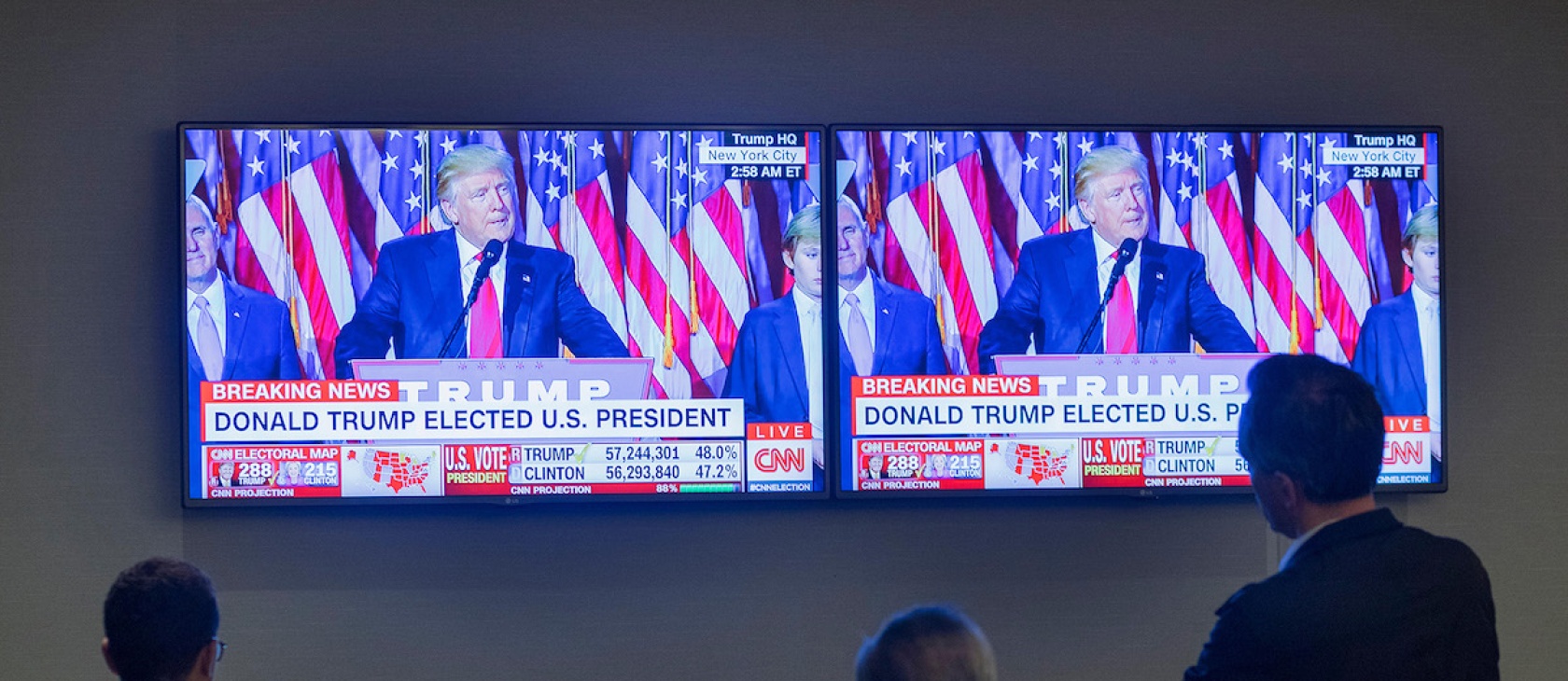

How American liberals came to their bizarre perceptions about that supposed rightist takeover of Christianity is actually an interesting tale. One critical moment came after Trump’s shocking victory in 2016, which drove serious heart-searching about the roots of that amazing phenomenon. Journalists, political scientists, sociologists, and ethnographers plunged into the deepest recesses of the Rustbelt states, and over the next couple of years they produced a series of striking books about the State of the Nation. They still make fascinating reading. These accounts focus on economic disasters and disappointments, which transformed cultural attitudes, and concepts of class occur very frequently. From my own personal observations in the decisive swing state of Pennsylvania, I was repeatedly stunned by the militant class consciousness of Trump supporters and their incandescent fury against “rich bastards” and what they had done to the country and the culture. Class anger was running at a level that might have persuaded Leon Trotsky to tell people to calm down a bit before they did something stupid. Surprisingly scarce in those various investigative accounts of Trump Country was the overt theme of race, except insofar as people complained that the said rich bastards were using immigrants to undercut wages. Nor, very noticeably, did religion play any significant role.

For liberals, this was genuinely scary stuff, not least in portraying Trump supporters as fairly rational actors and not as crypto-Klansmen. Clutching at what hope they could find, the media increasingly turned their attention to surveys showing the evangelical identification of a sizable number of Trumpists and other hard rightists. Breathing a sigh of relief, journalists and academics could now present the right as slaves of cynical Elmer Gantry preachers and snake-oil salesmen. I will just repeat a point that Hollinger scorns, but it is crucial: Those surveys count self-identification as evangelicals and not actual members or attenders of evangelical churches.

No credible evidence shows that this evangelical association persuaded or influenced people to vote in particular ways. We might equally postulate that people voted as they did for their own particular reasons and interests, as they understood them—and oh, by the way, they lived in communities and social networks where people happened to be evangelical. Correlation is not causation. You might also point out that Trump voters in 2016 drove very different vehicles from Clinton supporters. That fact reflected different levels of wealth and (by implication) of the education levels that contributed to higher incomes, but of itself it had no causal quality. Only an idiot would suggest that possessing a pickup truck made people vote for Trump, as opposed to being a common feature among people who behaved thus.

The most notable element of modern American Christianity is the decisive acceptance by most denominations of values that only a couple of generations ago would have been regarded as liberal or even radical.

Let me offer an analogy. Overwhelmingly, black Americans vote for Democrats, and they do so for reasons that are rational and comprehensible. They vote out of perceptions of their self-interest, both economic and cultural. If you ask those black voters about their religious loyalties, a large number will report being members of historically black Protestant churches, which, as I remarked, are commonly evangelical or Pentecostal. This does not necessarily mean that membership in such churches forms political attitudes. Rather, people have the politics they do, and they also follow given religious practices. Historically, those churches certainly did guide political development, supplying leadership and social networks. But if those churches vanished tomorrow, and black Americans suddenly secularized en masse, there is no suggestion that this would change political beliefs or voting patterns. Very sadly to note, the decline of institutional religion among those very black Americans likely means we will be observing such a process at work over the next couple of decades.

Hollinger’s book has the advantage of brevity (that is not a snide comment; writing concisely is an enviable quality). But every page invites challenge and refutation. Even the subtitle is ridiculous: “How Religion Became More Conservative and Society More Secular.” The whole book focuses on Christianity, or rather a subset of it he believes to have become Hard Right. Yet oddly, here, he is suddenly pontificating on “Religion.” So let’s play by his rules and address Christianity alone as synonymous with “religion.” The most notable element of modern American Christianity is the decisive acceptance by most denominations of values that only a couple of generations ago would have been regarded as liberal or even radical. Today it is absolutely unacceptable for any but the weirdest fringe sects to preach racial division or denounce “miscegenation.” Even if many churches will not accept same-sex marriages, virtually none preach that gays and lesbians are in any sense sick, diseased, or harmful. At the level of ordinary congregations, as opposed to hierarchies, many surveys have shown that sympathy for gay marriages and families runs very high, including among otherwise conservative denominations. It’s all part of American religion becoming less conservative.

The flaws of Hollinger’s book are agonizingly obvious. So why do I cite any positive qualities? In my view, Hollinger has bought into an unsubstantiated model of political reality that is thoroughly ideologically driven. Yet he is certainly correct about society as a whole becoming more secular, and he makes some fair comments about the evidence for people leaving religions and identifying their religious affiliation as “None.” The Nones became a major force at the turn of the century and presently constitute almost 30% of the population, the largest bloc in terms of religious identity. Recent surveys by the Pew Research Center suggest that they could constitute an overall majority within a few decades. There is a real phenomenon here, which probably does owe something to people accepting some of the horror stories he outlines in the book. Hollinger understands the issues well and offers an effective survey of the current literature.

On occasion, too, you still see flashes of the outstanding scholar and historian who has made so many major contributions. Just to take two examples: He offers a chapter on the influence of American missionaries on changing fundamental perceptions of other faiths and, by implication, the races that followed them. That then contributed massively to the liberalization of those “ecumenical” mainliners. This is basically taken from his 2017 study Protestants Abroad, but it remains a superb contribution to the subject. He is also very good on the significance of the very strong Jewish role in culture and politics during the 20th century, and how that undermined traditional notions of Protestant hegemony. That contributed to what “ecumenicals” were already confronting and coming to terms with.

Those two chapters, on the Jews and the “missionary boomerang,” are wise and well argued. I dearly wish the same insightful historian was more in evidence elsewhere in this present book.