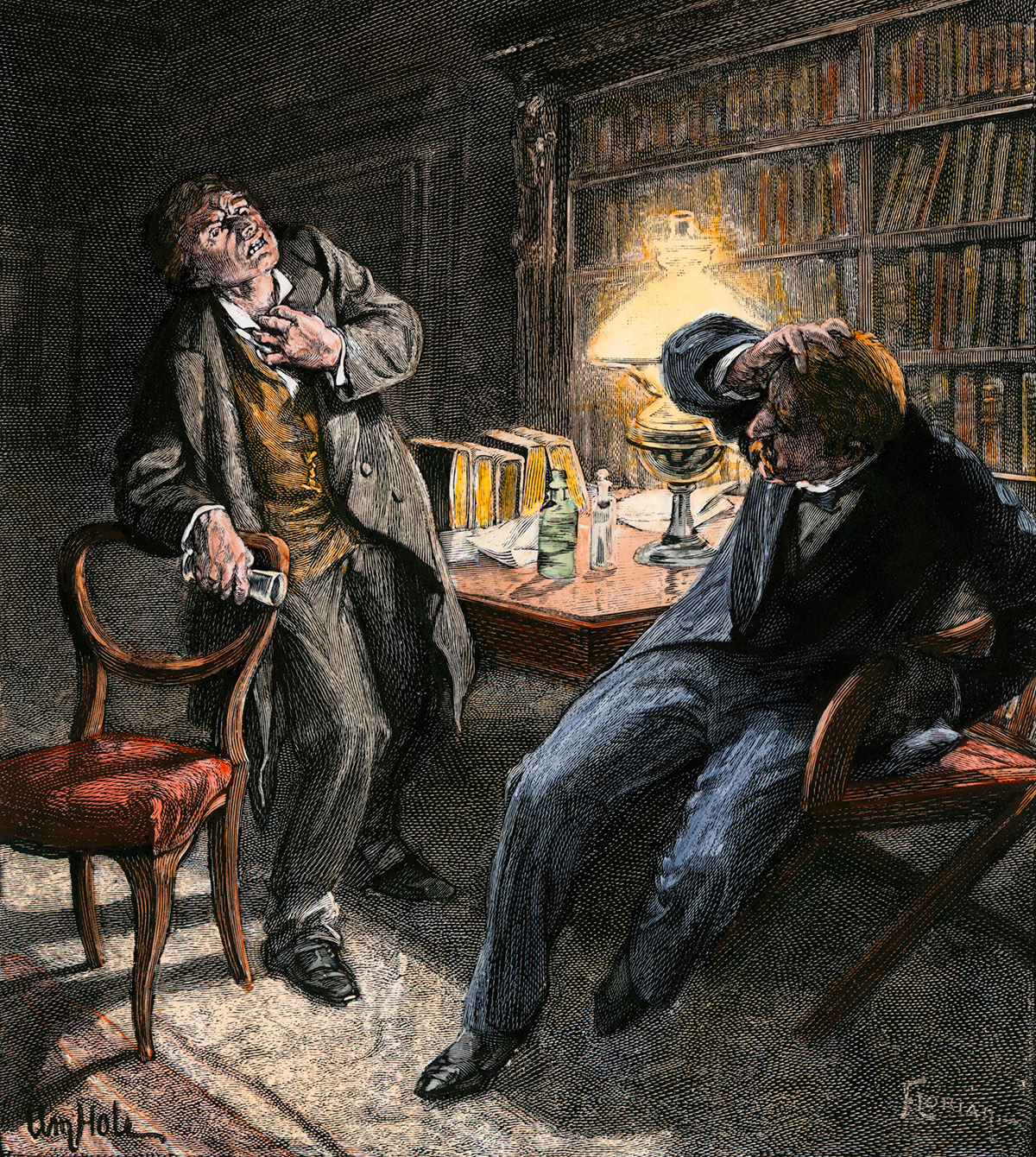

These days, many on the right are itching for revolution. Eager to dispense with what they believe is a hidebound conservatism that promoted restraint and narrow ideals at the cost of broader cultural and political victories, these rebels have embraced new philosophies ranging from integralism, Trumpism, Nationalist Conservatism, and even a devotion to the autocratic-lite populism of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who told attendees at last year’s Conservative Political Action Conference to “take back the institutions in Washington and in Brussels” and “Play by your own rules.” Depending on your political proclivities, these developments are either invigorating or like watching a tetchy Mr. Hyde emerging from the stable temperament of Dr. Jekyll.

The New Right has been sounding the death knell of “Conservatism Inc.,” fusionism, Reaganism, and neo-conservatism for a while now in an effort to forge a more pugnacious movement. But how do you build a new world from whole cloth without destroying the values you claim to be preserving?

The concerns of these would-be disruptors include conservatism’s perceived failure to halt the progressive left’s long march through cultural and educational institutions; the increasing power of the administrative state; the rise of “woke” corporations; the continued insistence of some conservatives on America’s unique responsibilities in world affairs; and the failure of the traditional free market capitalist message to confront present economic realities. Many books, essays, conferences, and organizations have sprung up to attempt to craft an agenda for these often-competing New Right impulses.

It is in this context that Jon Askonas, writing in Compact magazine, purports to tell us “Why Conservatism Failed.” One would hope that an obituary for conservatism would be more thorough than what Askonas offers, so to be charitable, let’s consider his essay a provocation rather than the official death knell for conservatism.

Nothing New Here

Conservatism’s obituary has been written many times before, of course. But Askonas claims to bring a new insight and a new indictment of conservatism’s devotion to tradition: “The conservative defense of tradition has failed—not because the right lost the battle of ideas, but because technological change has dissolved the contexts in which traditions once thrived.” Citing Marx, Askonas claims that “a technological society can have no traditions.”

Elaborating on this claim, Askonas argues that “modernity liquidates traditions for the same reason that a firm might liquidate an underperforming factory: to improve the allocation and return of capital.” This is an intentionally limited definition of tradition, one that purports to measure the usefulness of tradition as akin to a commodity that should be replaced when it becomes inefficient. Askonas also blames conservatism for too readily acquiescing to technological change. Using the example of the introduction of cheap agricultural fertilizers and the many unintended consequences its use had for the practice and culture of farming, Askonas claims this demonstrates “how extensive the social impact of a single technology can be, and how little the conservative defense of tradition offers in response to this sort of change.” For good measure, he throws in the charge that conservatives also lost the culture war, not because their ideas were wrong, but because of “the Pill and the two-income trap.”

None of this is new. In the 1950s in The Conservative Mind, Russell Kirk acknowledged, “For a century and a half, conservatives have yielded ground in a manner which, except for occasionally successful rear-guard actions, must be described as a rout.” Like Askonas, Kirk identified how, throughout the modern world, “things are in the saddle,” including “industrialism, centralization, secularism, and the leveling impulse,” and he indicted conservative thinkers for lacking “perspicacity sufficient to meet the conundrums of modern times.” A similar lament emerged in the work of mid-20th-century sociologists such as Robert Nisbet, who noted in The Quest for Community, “Surely the outstanding characteristic of contemporary thought on man and society is the preoccupation with personal alienation and cultural disintegration.”

And while Askonas enjoys citing Karl Marx, his argument is far more indebted to French sociologist Jacques Ellul, whose 1954 book The Technological Society examined in detail the erosion of moral and social values wrought by technological change. Another significant influence is Neil Postman, whose Technopoly was subtitled “the surrender of culture to technology.” There are many, many more—including, it must be said, Theodore Kaczynski, the Unabomber, whose manifesto included a special shoutout attacking conservatives that sounds quite similar to Askonas’: “The conservatives are fools,” Kaczynski wrote. “Apparently it never occurs to them that you can’t make rapid, drastic changes in the technology and the economy of a society without causing rapid changes in all other aspects of the society as well, and that such rapid changes inevitably break down traditional values.”

In other words, there is a rich (dare I call it) tradition of critical assessments of technology’s impact and unintended consequences, both from within and outside the conservative intellectual world, which Askonas surely knows but does not make mention of in his essay, perhaps because in those works tradition is treated as the complicated and nuanced thing it is, rather than the one-dimensional straw man Askonas needs us to accept so that his obituary for conservatism will make sense.

Are we a society without traditions? Should we refer to it, as Askonas does, in scare quotes as “Tradition”?

No.

A Tradition of Change

Askonas never offers a proper definition of the role of tradition, but philosopher Roger Scruton’s description will do: “For the conservative, human beings come into this world burdened by obligations, and subject to institutions and traditions that contain with them a precious inheritance of wisdom, without which the exercise of freedom is as likely to destroy human rights and entitlements as to enhance them.”

For conservatives, traditions are not static things; they can and must change to fit new circumstances.

Note that Scruton, like most conservative writers, more often speaks of traditions, plural, not “Tradition.” That is because many forms of tradition flourish in different communities, in different times and places, and of course not all of them (foot-binding, sati) are worth bequeathing to future generations. For conservatives, traditions are not static things; they can and must change to fit new circumstances. But conservatives also believe that such change should come slowly, thoughtfully, and with humility—weighing the benefits and drawbacks. As Kirk observed, “Conservatives respect the wisdom of their ancestors . . . they are dubious of wholesale alteration. They think society is a spiritual reality, possessing an eternal life but a delicate constitution: it cannot be scrapped and recast as if it were a machine.”

Conservatives believe that traditions serve as moderating influences on the deeply human desire for change, not a means of suffocating that desire. As Edmund Burke wrote in a 1792 letter, “We must all obey the great law of change. It is the most powerful law of nature, and the means perhaps of its conservation. All we can do, and that human wisdom can do, is to provide that the change shall proceed by insensible degrees. This has all the benefits which may be in change, without any of the inconveniences of mutation.” Or, as Kirk put it, “Conservatism is never more admirable than when it accepts changes that it disapproves, with good grace, for the sake of a general conciliation.”

Askonas is dismissive and impatient with this sensibility because he sees it as the handmaiden to our capitulation to the technological society. “In between great-books seminars, conservatives have decried any interference in what technologies the all-knowing market chooses to build, while taking no stance on what technologies we ought to build,” he complains. This is misleading, as it elides some crucial distinctions between conservatives and libertarians; conservatives continue to battle their libertarian friends about the excesses of the free market (just ask those of us who have extremely libertarian colleagues with whom we often clash). Conservatives are in fact on Askonas’ side of this argument and would agree that technologies that emerge from unfettered free market capitalism can often have a destructive impact on society.

But a blanket denunciation of the uselessness of conservative tradition allows Askonas to argue that the only path forward is revolution rather than reform: “We can no longer conserve. So we must build and rebuild and, therefore, take a stand on what is worth building.” A touch more cynicism crept into remarks Askonas made during an appearance on a podcast in March, when he accused conservatives of trafficking in nostalgia as opposed to principles. “It is the combination of the same kinds of practices that destroy the tradition with a mere sort of sickly veneer of the way things used to be,” he said, comparing modern conservatism to the kitschy horror of a Thomas Kincaid painting.

This would indeed be horrifying if Askonas’ claim that conservatives failed to reckon with the technological changes around them, thus effectively participating in their own extinction, was true. In fact, conservatives have spent decades building institutions and communities to combat just those changes. Askonas should know; he’s written essays (many of which I admire) for several of them, including The New Atlantis, a journal that for 20 years has been dedicated to documenting the good, the bad, and the ugly of technological transformation, and for which I was fortunate to be one of the founding editors.

In addition, conservative thinkers and policy experts have for years argued for more guardrails to protect against the excesses of technology, particularly when it comes to its impact on children. Many thinkers have challenged the totalizing vision of technology with what can be broadly understood as a conservative sensibility: Nicholas Carr, L.M. Sacasas, Matthew Crawford, Jaron Lanier, Alan Jacobs, Sherry Turkle, and many more have reckoned with what is lost as well as gained when technology supplants older ways of doing things.

Prudence and the Pill

But we should not limit ourselves merely to personal technologies and the Internet. What of the conservative response to technologies of reproduction, cloning, and human enhancement?

In the realm of bioethics, the late Edmund Pellegrino and Leon Kass, among others, offered a compelling example of how to invite public debate about deeply challenging moral questions at the beginning and ends of life with regard to cloning, genetic manipulation of human embryos, and stem cell research, for example. The efforts of such conservative thinkers helped forestall the abuse of many technological powers by constantly insisting we ask the question, “Just because we can do something, should we?”

Or, to return to Askonas’ example of agriculture and the communities that develop around small-scale as opposed to industrial farming, groups like Front Porch Republic champion the integrity of place, scale, and face-to-face community in a world where technology promises the elimination of all three. Askonas name-checks Roger Scruton in his essay, but he fails to note that when he was alive Scruton was himself the owner of a farm in Wiltshire and famously championed the small-scale agriculture Askonas claims conservatism was helpless to save.

“A hundred years ago,” Scruton told Dominic Green in an interview on his farm in 2017, “people in this part of the world would eat turnips and carrots to get through the winter. Now, they have avocado pears and rocket salad.” Scruton understood what globalization had wrought, and unlike the monolithic portrait of conservatives that Askonas paints, Scruton was an outspoken critic of libertarian free marketers who refused to reckon with the costs of globalization to communities such as his. Scruton also understood that nurturing his particular farm and community meant having to adapt to certain technological realities.

“You can’t globalize the old rural economy,” Scruton said. “By its very nature, it’s a local thing, and that’s what we’re trying to support with this little festival,” referring to a local apple festival he and his family created to help support local farms, including their own. The virtues of this local orientation would have been familiar to Edmund Burke, as would Scruton’s willingness to undertake reforms to keep certain traditions, such as a successful family farm, alive.

This conservative approach to change is something Askonas fundamentally misrepresents in his obituary for conservatism. In doing so, he overlooks evidence of conservative resilience and resistance to technological capture. Consider the many parents’ groups, like Wait Until 8th, which encourage the formation of communities committed to delaying their children’s exposure to technologies like the smartphone until they are older. Or the ongoing backlash, some of which is yielding state and federal legislation, against the exploitation of children’s attention on social media.

There are even conservatives thinking about our technological future—and noticing that some longstanding conservative arguments have already won the day. As John Ehrett points out in a recent essay in The New Atlantis on the possibilities of conservative futurism: “Conservatives have, in a sense, won the argument about Big Tech. The poisonous effects of Internet-centric culture and a screen-mediated world are now well known across partisan lines, and sooner or later a reckoning will come.” Ehrett urges conservatives to craft “meaningful answers to the question of why we need innovation” but to do so in a way that grounds that process in an understanding “that human creativity is a participation in an infinite creative act, reorienting technological investment into the service of a higher good.”

Will to Power vs. Curb Your Enthusiasm

Ultimately, Askonas’ frustration with conservatism is about power, not capital-T Tradition. “Before we recover a human way of thinking, we may first need to address a more practical question, first posed by Nietzsche,” Askonas writes, “‘Who deserve to be the masters of the earth?’ Corporations? The Chinese Communist Party? The National Institute of Health? The Department of Defense? Or human beings living according to their natures.” He argues that we don’t need the “kind words and tax credits” of old-fashioned conservatism but “a serious program of technological development.”

Conservatism would answer Nietzsche’s (and Askonas’) question quite simply: none of the above. Indeed, for conservatives, the traditions Askonas sees as useless are precisely what help curb and civilize mankind—and thus allow a level of self-governance that doesn’t require a Communist Party to impose its will and that can hold the leaders of its own institutions accountable. History has shown that encouraging mankind to live “according to their natures” tends to end in war, violence, scarcity, and general brutality, with the strong ruling the weak. (Conservatives, given their understanding of human nature, would warn against such encouragement, too.)

As for Askonas, whom would he entrust with designing the “serious program” he desires? Who decides who enforces the rules of this program? And who benefits? “Those who look to build a human future have been freed from a rearguard defense of tradition to take up the path of the guerilla, the upstart, the nomad,” he writes. His choice of role models is instructive, both for what they tell us of his understanding of conservatism and tradition, and what they portend for a future devoid of either.

Ultimately Askonas’ frustration with conservatism is about power, not capital-T Tradition.

Consider the “guerilla.” Among the more famous of history’s guerilla fighters are men like Mao, Fidel Castro, Josip Broz Tito, and Che Guevara, the last of whom literally wrote the book on the practice. What kinds of “serious programs” did they build once they seized power? In the case of Mao and Castro, a punishing and deadly authoritarianism built on a bed of empty utopian promises and the bones of their citizens; for Tito, purges, fraudulent elections, show trials, and eventually ethnic cleansing and the collapse of Yugoslavia.

Likewise, the “upstart” Askonas praises is a type more skilled at destruction than building.

Upstarts “move fast and break things,” as Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg so memorably put it. Although something new, shiny, and even useful might come from the upstart, he rarely reckons with the wreckage he leaves behind. As for the “nomad,” always a minority lifestyle, he embodies impermanence, effectively living as a social parasite on the order created by others, never experiencing either the risks or rewards of setting down roots in one place.

Traditions are larger than any one individual who might embody their characteristics. Yet Askonas’ preferred leaders of the next age are examples of radical individualism—an individualism whose fruits tend to be either destruction, authoritarianism, or both.

Among a certain segment of the right, however, the destruction is the point. As John Daniel Davidson, writing on The Federalist website in 2022, bluntly put it, people affiliated with the right should “stop thinking of themselves as conservatives (much less as Republicans) and start thinking of themselves as radicals, restorationists, and counterrevolutionaries.” They should also, he argued, use the levers of power to their advantage: “The government will have to become, in the hands of conservatives, an instrument of renewal in American life—and in some cases, a blunt instrument indeed.” As for who will wield that power and how they will do so fairly, Davidson says such questions can be answered “after we have won the war.” Spoken like a true guerilla.

Unlike the guerilla or the upstart or the nomad, conservatives understand that society is not for the enjoyment of any one individual.

Our Chinese Future?

If, as Davidson and Askonas suggest, we rid ourselves of tradition and instead enact change through the seizure of power by guerillas, upstarts, or nomads, then whatever they build will be built without guidance from the past, for this vision only works if you jettison the messy realities of history (which is perhaps why it is so appealing to political philosophers and political scientists, and rather less so to historians).

Askonas misunderstands how conservatives measure progress: not in decades but in epochs. In the U.S., for example, history teaches a peculiarly important lesson about conservatism and revolution: you can’t have both. Yes, America’s Founders, as revolutionaries, seized power from England. But then they immediately went about devising a way to share it among many different groups—first, and incompletely, by way of the Articles of Confederation and then, ingeniously, through our Constitution.

Askonas’ vision gives us radicals, reactionaries, and counterrevolutionaries whom he promises will build something new and better from the ashes of a dead conservatism. But where are the (small r) republicans? Where are the people who can live, govern, and thrive after the revolution? Judging Askonas on the future society he hints will replace a dead conservativism, the nation that most resembles his vision is not a free and diverse America, but China.

The Chinese surveillance state doles out social credit to good citizens and imprisonment to minorities like the Uyghur people. But what is this if not the state making use of its technological powers, unencumbered by Tradition, to build a “better” society? Birthed by a guerilla (Mao), China’s leaders embarked on a relentless effort to expunge Tradition and Values (and murder any naysayers) during the Cultural Revolution. Its political elite now controls what the populace sees and hears, and they have no patience for the inconveniences of history (such as the bloody events that unfolded in 1989 in Tiananmen Square).

Conservatism is not merely a game of winners and losers as Askonas too often portrays it to be. It is a way of understanding the world and being in the world that takes as its starting assumptions arguments from common sense and the experience of all who came before. Despite decades of postmodern and poststructuralist theory and rapid technological change, such a view still holds great appeal. In a culture that celebrates fetishization (even fetishizing the normal in the form of normcore), common sense, as well as devotion to family, community, and country, can be a steadying force.

What first principles will Askonas’ new world be built upon?

Respect Your Dead

Revolutionaries always predict a more high-minded future for their schemes. Conservatives’ unenviable but crucial task is to think through the logical conclusions of such schemes, explore their likely unintended consequences, and always contrast the utopian vision with the realities of human behavior and history.

Unlike the guerilla or the upstart or the nomad, conservatives understand that society is not for the enjoyment of any one individual; instead, it is, as Burke famously argued in Reflections on the Revolution in France, a partnership “not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.”

Askonas and others are correct to point to how our use of technology has strained that partnership in significant ways. The pandemic experience revealed how fragile is the bond of trust between citizens and our institutions; how little accountability there is during times of crisis from those who are deciding how people should live; and how easily fear can lead even the well intentioned down illiberal paths.

But conservatism counsels thoughtful adaptation, preserving what is most important about institutions, noting also what might change, but not promoting wholesale revolution. Askonas’ eagerness to shrug off the mantle of conservatism to dive headlong into building new ways of being in the world that conform to current technological capabilities also fails to reckon with another serious blind spot: How will this new world, the one better adapted to technology than its conservative forebears, create trustworthy institutions from whole cloth? As Scruton reminds us, “Good things are easily destroyed but not easily created.”

The conservative temperament, with its respect for history and the homage it pays to the “democracy of the dead,” as G.K. Chesterton called it, does not view progress as predictable and linear, nor every new thing as a sign of progress. And it recognizes that change cannot happen only from the top down, no matter how well intentioned the elite in charge believe themselves to be. Out of humility rather than pessimism, it reminds us that sometimes the proposed cure ends up being worse than the disease. In our technology-saturated society, convinced we can achieve lives of frictionless ease in metaverses of our own making, conservatism reminds us to come back down to earth, and to the reality of our limitations and our wonderfully contradictory, creative, messy, and extraordinary humanity.