Bill Crosby credits General Electric Co. with powering his family into the middle class starting with his grandmother, Vera Baskin.

Baskin was born in 1888 on a farm in Mississippi, where she grew up with seven brothers. She lived through the Great Depression, moved to Atlanta and worked as a bank teller her whole life. She learned the value of buying stocks, particularly stocks in big, stable American blue-chip companies. So she loaded up on General Electric – symbol GE – amassing nearly $500,000 worth of shares and making it a third of her portfolio. It functioned beautifully as a consistent growth stock (it grew to more than $2 million for Crosby’s family) and one that paid a healthy dividend each quarter.

Investors lost both money and faith in GE. In the company’s heyday, no one would have predicted such a stunning fall.

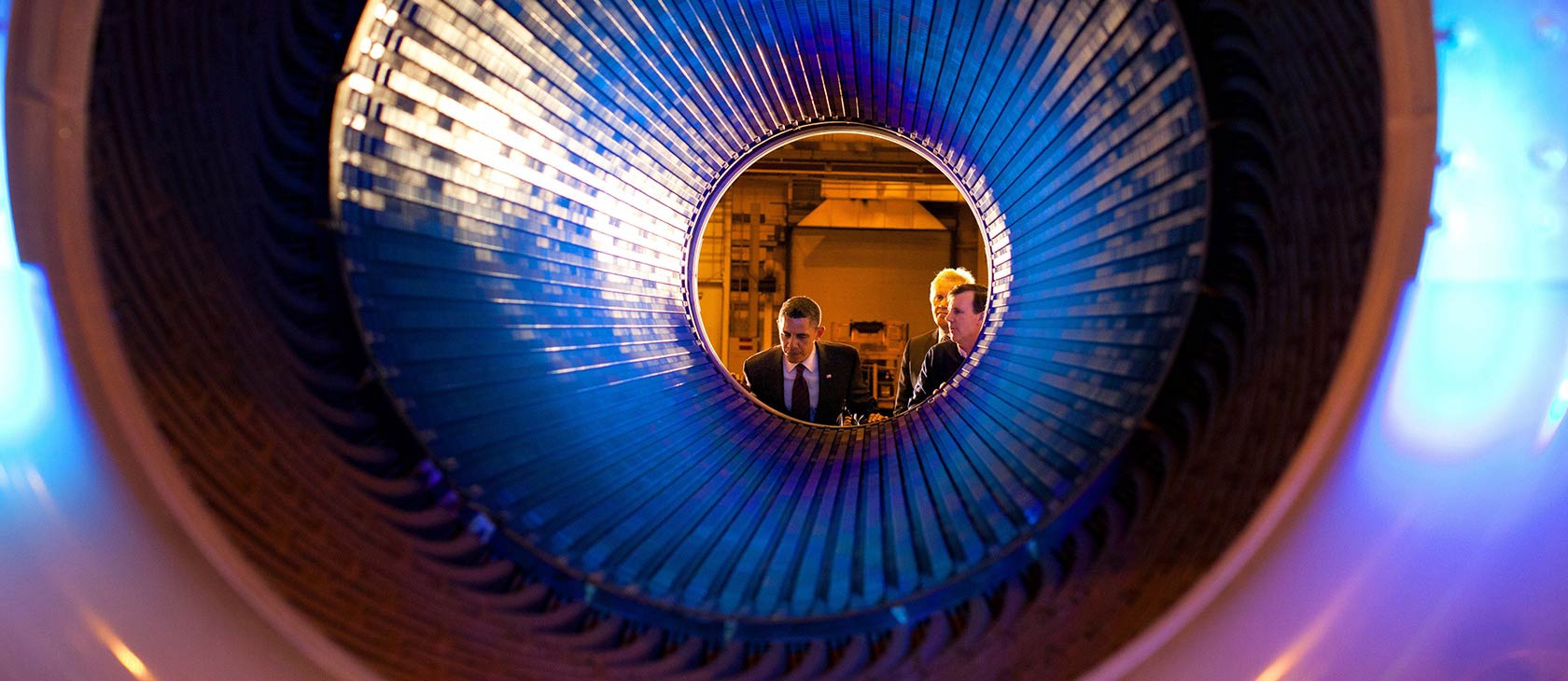

“They believed in it,” Crosby said of his grandmother and mother’s view of GE. “They [GE] were the quintessential conglomerate of that age in which everyone seemed to be horizontally integrated.” It was a classic 20th century corporate strategy -- owning supply chains and finance arms to issue credit plans to sell industrial products to customers – whether airplane engines to airplane makers or wash machines to housewives.

After a century of growth, GE went from being arguably the most powerful and dominant company on Planet Earth to one of its most disappointing, troubled and wayward in the last 20 years. Poor strategy and a tough economy led to layoffs at GE factories from Kentucky to Pennsylvania. Investors lost both money and faith in GE. In the company’s heyday, no one would have predicted such a stunning fall.

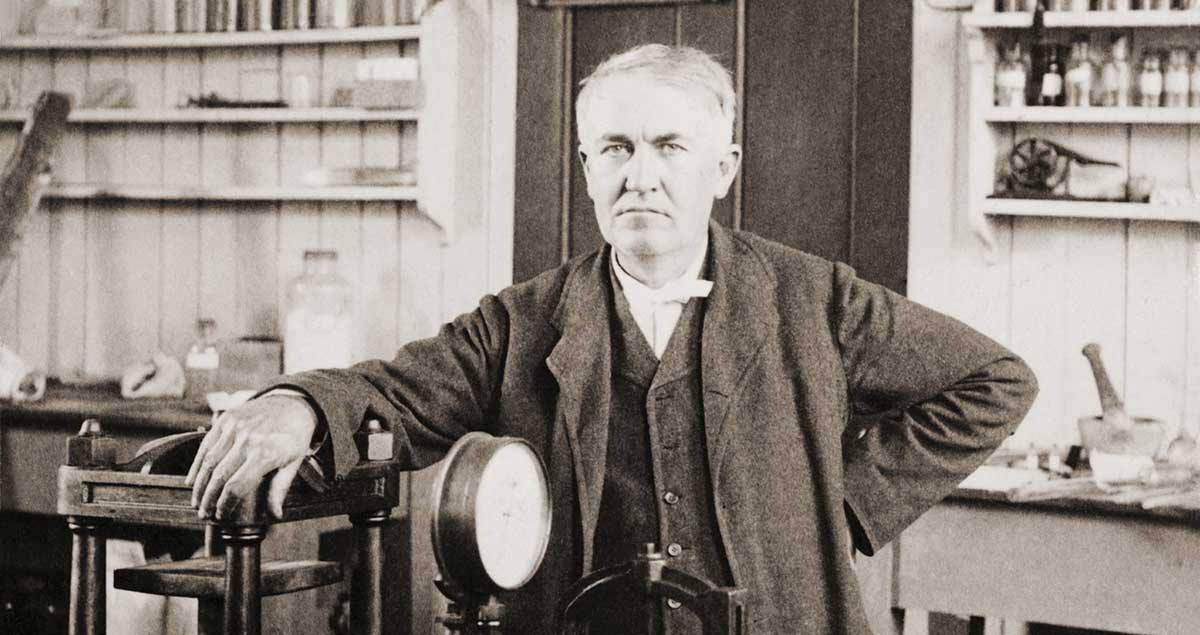

Thomas Edison and the birth of GE

Just eight years before Baskin was born, Thomas Edison received patent No. 223,898 in January of 1880, one of 1,093 patents he would receive in his lifetime. But this one was different. This patent explained his electric lamp design that used a high-resistance carbon filament in a sealed glass container. It was the incandescent light bulb, that symbol of invention itself.

Similar to recent capitalist geniuses Steve Jobs, Elon Musk and Bill Gates, Thomas Edison had his share of personality shortcomings and business misfires. But he envisioned a host of technologies ranging from electric light, recorded sound, moving images and electric cars. Edison’s life included fierce rivalries with other inventors such as Alexander Graham Bell, George Westinghouse and Nicolai Tesla. He also developed close friendships and working relationships with luminaries such as J.P. Morgan, Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone.

The nation had moved on from the dark chapter of Civil War, celebrated a centennial of independence from the British and was starting to find its footing as an industrial powerhouse. A period of optimism and innovation was emerging in the adolescent country.

On New Year’s Day in 1892, the United States began receiving immigrants at Ellis Island. Waves of hard-working people with talents and technical abilities flooded into New York Harbor from countries like Serbia and Germany into the booming nation, ready to make a new life in a land of opportunity. Electricity was literally the hot industry of its time and the Northeast was the Silicon Valley of its day.

The wizards of that electric age – Tesla, Westinghouse and Edison -- battled for supremacy in a 1900s version of Game of Thrones, with New York bankers such as J.P. Morgan placing bets on who would win the creative and commercial struggle. Thomas Edison, the prolific inventor, earned the nickname the “Wizard of Menlo Park” and was arguably the most famous man in America.

When Edison Electric Co. received patent No. 223,898, courts forced competitors such as Thomson-Houston Electric Company to pay license fees to Edison on the incandescent lamp, handicapping profits and giving Edison a massive advantage.

In some American cities, two electrical lighting systems existed – one based on Edison’s direct current method and another built on the Thomson-Houston alternating current system. No electrical plants could be built without infringing on patents from several companies. Consolidation only made sense. By April 15, 1892, Edison’s company reached a merger agreement with Thomson Houston, combining the brilliance of two rivals under the name General Electric Company.

As the company started operating under its new name on June 1, 1892, Charles Coffin stood out as the managerial and visionary force. Both he and Thomas Edison served on the board of directors of the new company along with other famous business names of the time including J.P. Morgan. As the lone electrical mind on the board, Edison clung stubbornly to his preference for direct current technology (the one he invented). Later, he resigned from the board to focus on his sundry research and inventions.

An economic depression hit the United States from 1892 to 1897, the lights nearly switched off at GE. Some paranoid citizens and critics started pointing to the combined GE, even in its first year, as a “combine” or “a trust.” Some attacked it as “a monopoly with menacing possibilities.” Some questioned its financial statements early and often. A weekly magazine called Electricity attacked the company’s bookkeeping methods and impugned the character of Coffin himself. It claimed the company was overcapitalized and took on too much debt, according to the 1943 book “Men and Volts: The Story of General Electric” by John Winthrop Hammond.

Historians point to GE’s early visionary chief, Charles Coffin, for establishing its early ideals that prevented it from becoming a soulless corporation for the first decades of its life. As the two companies merged operations, Coffin had a knack for streamlining business processes and also unlocking new innovations in manufacturing light bulbs and other products. The managerial and creative talent helped GE weather that initial storm and thousands more than would emerge.

In its first century, many small investors like Vera Baskin flocked to GE because it represented stability and consistency. They passed this income producing stock onto their children and grandchildren. Baskin left nearly $1 million in GE shares to her grandson and three granddaughters. Along with that, she left a legacy of investing, working hard and being frugal. Her grandson, Bill, became a national bank examiner, spotting fraud at banks around the country.

Tampa-based attorney Guy Labalme acquired his first stake in GE in 1941 when his mother died and left him with 300 shares. He continued bullishly buying until he had 56,000 GE shares by 2009. Like Crosby’s family, Labalme grew accustomed to GE paying sizable dividends for decades, viewing its shares as an “income stock” for which regular Americans could rely upon in retirement almost as reliably as a pension fund, a 401k plan or Social Security program. “I’ve always believed in GE. I always felt that GE is a microcosm of America,” he said. “Basically, I thought if the company went to pot, so would the country.”

The rise and fall of modern GE

Companies, like people, have an identity. They have a name. They have a lifespan. Their name can be changed. Great people like Thomas Edison can see their name erased from the title of companies, their legacies sometimes forgotten or misrepresented. The company’s life span, like the person, doesn’t last forever. With bad luck, bad strategic decisions or natural causes, a company can struggle and die.

With its logo on sundry products from washing machines to light bulbs and its heavy spending on advertisements from Madison Avenue, GE developed a recognizable brand around the world. Its brand was so iconic that artist Andy Warhol made a series of massive silkscreen images of The Last Supper in 1986 featuring the GE logo over the left shoulders of Christ and his disciples, the Dove soap logo over their right featured a dove, representing the Holy Spirit. For Warhol, a student of advertising and corporate branding, the GE logo bore almost religious symbolism in the land of the American dream.

It’s a company made famous by its origins to Edison and built up over the 20th century by powerful CEOs like Ralph Cordiner, Reginald Jones and Jack Welch. GE in some ways, as Labalme suggested, has been a proxy for America – a huge diversified company that became an engine of profits, jobs, and innovation over time, gobbling up smaller companies and functioning with a conglomerate federalism.

At its peak, GE employed roughly 330,000 people in factories and business units worldwide, which reported ultimately into the mother ship in Fairfield, Connecticut (now moved to Boston). GE was the highest valued company on the U.S. stock markets in 2000. Now, less than 20 years later, tech companies such as Apple, Alphabet, Amazon and Facebook all enjoy higher valuations and GE was not among the top 100 companies in market capitalization in 2019. GE’s cost structures – its employees, raw materials, factories -- are much higher than the tech giants.

In 2018, 283,000 GE workers generated $121.6 billion in revenue but a $22 billion net loss. Meanwhile, in the same year, Facebook employed fewer than 36,000 people to generate $55.8 billion in revenue and $22 billion in net income. Google (Alphabet) reported 98,771 employees who generated $136.8 billion in revenue and a $30.7 billion net gain in 2018.

If Apple is a company changing our lives most dramatically in the 21st century, one could argue GE was that company in the 20th century. It commercialized light bulbs, electric home appliances, jet engines, radio and television, x-ray machines, vacuum tubes and industrial plastics.

“For most of its 126-year history GE has exemplified the fecundity and might of corporate capitalism,” said a February 2018 cover story in Bloomberg BusinessWeek. “It manufactured consumer products and industrial machinery, powered commercial airlines and nuclear submarines, produced radar altimeters and romantic comedies. It won Nobel Prizes and helped win world wars.”

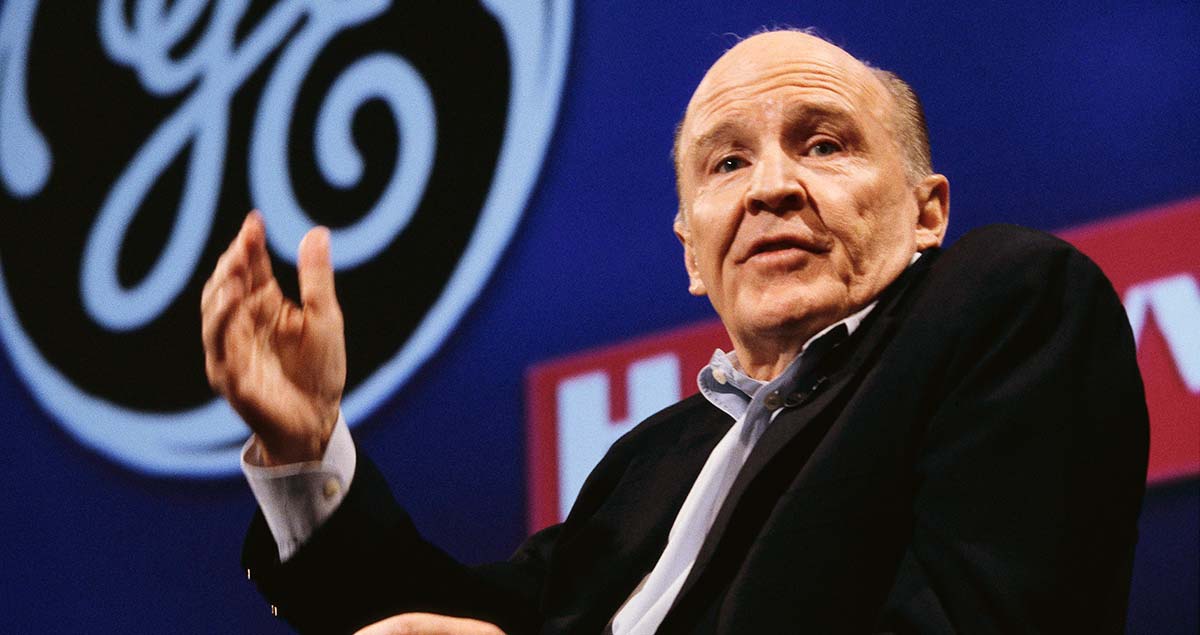

Neutron Jack

During his 20 years running GE, Jack Welch saw the company’s market value increase 28-fold, making it America’s most valuable company. Fortune magazine named him “Manager of the Century.” GE was sometimes called “The House that Jack (Welch) Built.” He was a rock star CEO.

Welch led GE from 1981 to 2001, a time in which revenues more than quadrupled and its market value rose from $13 billion to $410 billion. He viewed GE as an in-house MBA program, better than Harvard, Columbia and Wharton MBA programs. And, true, GE was a CEO factory as other Fortune 500 companies – including Honeywell, Boeing, ABB, Medtronic and others -- often recruited their CEO talent from upper ranks at GE.

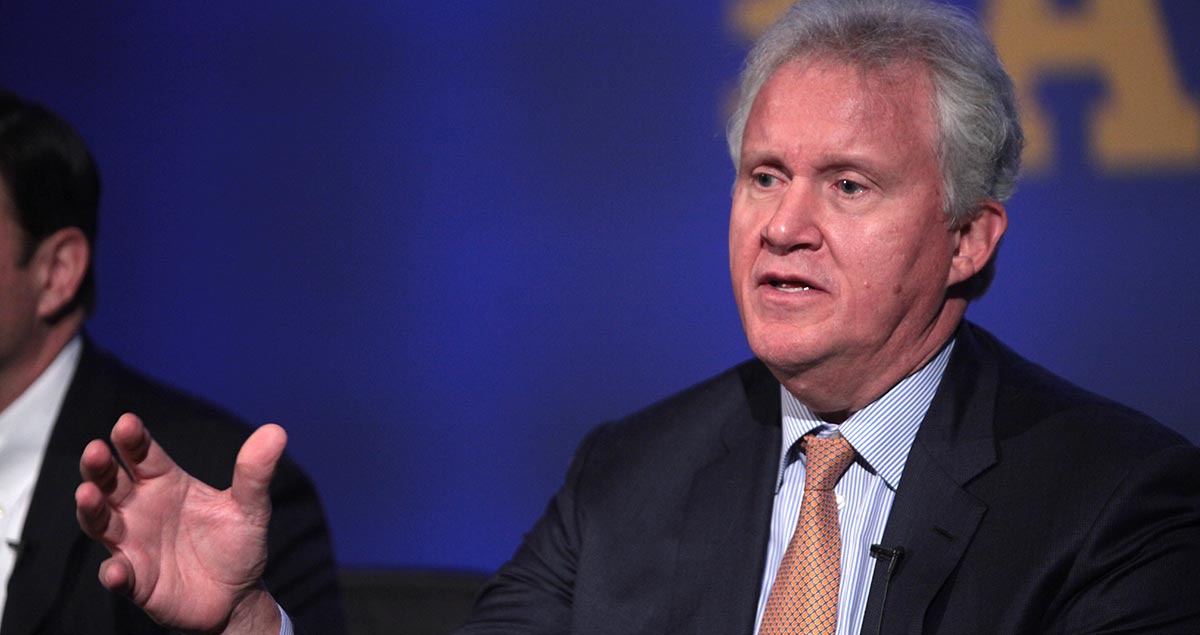

From among several executives gunning for the top job at GE in the late 1990s, Welch selected Jeff Immelt as his successor because he felt the life-long GE executive was “most comfortable in his own skin.” It was an odd pick in some ways because Immelt was a jock, a preppie, a lifelong winner. Welch was more of an underdog.

Welch was a working-class kid from Boston who had smarts and drive to grind his way up from entry-level engineering jobs to become CEO and to grow GE to become the largest and, arguably, most admired company in the world. Welch stood 5’7” and possessed a sharp temperament and a pugnacious manner of speech in his dealings with subordinates. He made counterintuitive bets, buying companies for a low price and selling them at a higher price. He would interrogate people bringing an idea to him, striving to poke holes in their logic and sales pitch. He valued counterintuitive thinking, a dogged work ethic and a meritocracy culture. Welch pioneered lean management techniques, cut bloated corporate staff, removed layers of management and accelerated decision processes at GE.

The fabled technique of firing the bottom 10 percent of the GE workforce earned him the nickname “Neutron Jack.” It’s a practice he denies but a label he cannot shake. Some management theorists now view Welch’s methods as dated, belonging to the 1980s. Others criticize him for being too dependent on GE Capital, which made up half of GE’s business by 2001.

Upon retirement, Welch wrote best-selling books about leadership. He gave high-priced motivational speeches and started a for-profit college that evangelizes for his 1980s and ‘90s recipe for success. “You can win without being upbeat – if every other star is aligned – but why would you want to try?” he wrote in his book “Winning” with his third wife, Suzy Welch, in 2005.

Boardroom hubris

Immelt was a calm, smooth executive. He was a tall jock who played football at Dartmouth and went on to Harvard Business School. He joined GE after Harvard and spent his entire career there, moving up the ranks of various business divisions before becoming the next CEO.

Immelt’s father had worked at GE in Cincinnati. Immelt was tirelessly devoted to the same company. He was academically gifted, a confident leader and a good communicator. But, during his tenure as CEO, his decision-making on deals didn’t seem to have the foresight and the critical vision of Welch. If Welch brought the deadly sin of pride and ego to GE, Immelt had a knack for ill-timed acquisitions and deals (the sin of greed) that fed operational gluttony, another deadly sin.

At an off-site strategy session away from GE headquarters in 2006, the senior leadership team of GE Real Estate set up a meeting with Immelt. They worried that GE had grown too large in real estate while they saw a real estate bubble forming. They had an idea on what to do.

Michael Pralle, then CEO of the real estate division, and his team suggested to Immelt that GE sell 51 percent of its real estate assets – perhaps to another firm such as insurance giant AIG or private equity firm KKR -- as a way to cash in from the boom and to protect the company from losses and risk of a bubble. People present at the meeting told me that Immelt rejected the proposal as the "dumbest f***ing idea!" and said, "Why would I sell half of the best real estate business in the world?"

The government had to step in to rescue GE and put it into the classification of companies that were “too big to fail.”

Just a year after the meeting with these lieutenants, the real estate division took the biggest hit of any division within GE during the financial crisis and damaged the company severely, possibly fatally. The government had to step in to rescue GE and put it into the classification of companies that were “too big to fail.”

Certainly, Welch left Immelt with challenges, including problematic insurance and plastics businesses to sell and the repercussions of a botched attempt to acquire Honeywell Inc. Plus, Immelt became CEO in September 2001, a few days before terrorist attacks rattled the economy and the insurance industry, where GE was a major player. But Immelt can't blame all his woes on being dealt a bad hand. He “made capital allocation mistakes under his own watch,” said Jeff Sprague, an analyst who followed GE at Vertical Research Partners. Sprague pointed to expansion into homeland security, real estate and the mortgage industry as lousy moves, heading directly into overvalued bubbles.

Both Welch and Immelt loaded up on financial assets, seeing outlandish profits rise as GE loaned money for customers to buy its expensive MRI machines, aircraft engines and power equipment. Finance seemed like the magic bullet to shore up the industrial giant. Its profits quadrupled as it added credit card companies, subprime lenders and real estate. Even so, Immelt served on the board of the New York Federal Reserve between 2006 and 2011, giving him possible insight into warning signs of the economy.

From 2001 until mid-2010, GE went on a shopping spree and announced 624 deals for $181.9 billion in acquisitions, according to Dealogic. Most of the money went into real estate, with 93 deals totaling $42.9 billion, and finance, with 115 deals for $42.5 billion. Most notably, it acquired sub-prime lender WMC Mortgage in 2004 for an undisclosed sum. The Burbank, Calif., company made $33.2 billion in loans in 2006 and ranked fifth among sub-prime lenders, according to trade publication Inside B&C Lending.

Success begets failure

During the commercial real-estate collapse of the early 1990s, GE was a big winner, making billions buying and selling distressed assets from the Resolution Trust Corp., the government thrift-bailout agency. Insiders say GE executives referred to its $90 billion commercial property business internally as “the honey pot” because the company for years used it to meet earnings by simply selling a building or two. GE also used short-term debt financing to make earnings. During the housing crisis and subsequent global financial crisis starting in 2008, however, those honey pots dried up and GE started to miss earnings projections for the first time and found itself cash poor.

As GE missed its quarterly earnings target by a whopping $700 million in April of 2008, Welch went on CNBC and expressed his disbelief in his handpicked successor, Immelt.

“I’d get a gun out and shoot him if he doesn’t make what he promised now,” Welch said, sending shockwaves through the financial community as it witnessed the rare spectacle of a former CEO slamming a current one. Weeks before, Immelt had insisted that GE would meet earnings projections, but the profit fell 6 percent compared to a year earlier and investors were alarmed.

The earnings miss perhaps signaled the oncoming housing and financial crisis. But Welch saw it as a leadership lapse. “Here’s the screw-up: You made a promise that you’d deliver this, and you missed three weeks later!” Welch said. “Jeff has a credibility issue! He’s getting his ass kicked!”

Welch was used to plain talk and direct criticism. He continued his rant on CNBC. “I’m not here defending what happened,” he said. Then, he shifted into a blistering defense of the conglomerate model he had built and championed at GE and which he now saw was at risk in the hands of his successor.

Welch, 72, never again commented publicly about Immelt or other current GE executives or the company’s performance. Sources at the company once told me they informed Welch that his pension and benefits would be in jeopardy if he criticized the company or its executives publicly again.

Immelt did lose reams of credibility between 2007 and 2010 as real estate and finance companies that GE owned took a beating in the recession. The company’s pivot away from industrial business and toward financial services during the 1990s and early 2000s under both Welch and Immelt proved a lousy strategy as it took GE head-first into sub-prime mortgages, the overvalued real estate sector and ballooned GE Capital to more than $600 billion, placing GE amid the top 10 Wall Street banks in terms of financial assets.

In 2007, GE abandoned subprime lending and sold its subprime mortgage broker WMC for $100 million after a total of about $1 billion in reported losses. As those bubbles burst between 2007 and 2011, the proud – some would say arrogant – American conglomerate was forced to fight for its very life.

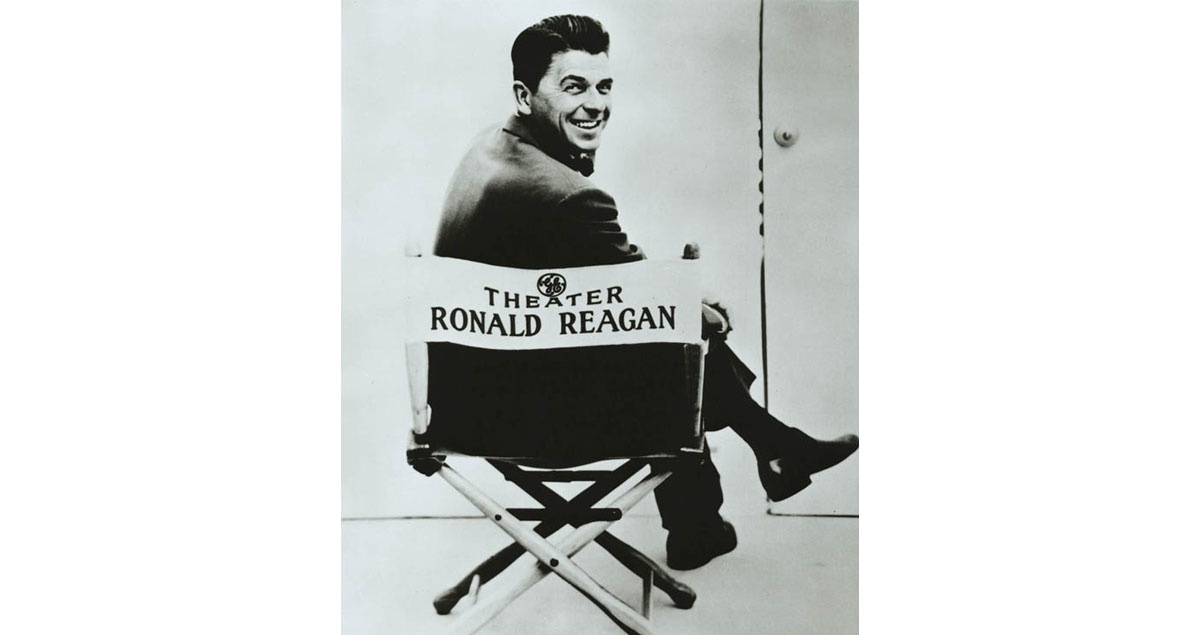

From Ronald Reagan to crony capitalism

Over the years, the company has been associated with Republican politics. President Ronald Reagan, voice of GE ads and host of the GE Theater television show from 1954 to 1962, said the views he encountered at GE helped transform him into a free-market conservative who believed in limited government. Former CEO Welch was a prominent supporter of several Republican presidential candidates, including Reagan.

Reagan ... said the views he encountered at GE helped transform him into a free-market conservative who believed in limited government.

As Wall Street investment bank Lehman Brothers imploded in 2008, real estate defaults mounted at GE and other large real estate players. As cash dried up, those companies with heavy debt were left exposed on the beach without a bathing suit, sunburned and humiliated. Immelt was forced “to phone President George W. Bush and ask for a line of credit to keep the company afloat,” writes Bill George, a Harvard fellow and former Medtronic CEO, on CNBC.com.

As the financial crisis worsened, GE was soon on its knees, lobbying and groveling before a Democratic administration in Washington, begging to be included in government bailout programs, emergency lending programs and other benefits that would function as life support to a wounded behemoth. Amid the company’s woes, the government threw GE a life preserver in the form of loans from the Federal Reserve and access to the FDIC's Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program in 2008 and 2009. The vagaries and lifelines didn’t stop there. Immelt was forced to take $3 billion from billionaire Warren Buffett in October of 2008 with a promise to pay him back $4.2 billion in subsequent years.

In February of 2009, Immelt restated his position that the company’s quarterly dividend was safe and wasn't constraining the company. "We've got the cash flow to pay the dividend," Immelt said in a Feb. 5, 2009, interview. But then a few weeks later on Feb. 28, GE cut its dividend by 68 percent, the first time it reduced its dividend in 71 years. That move saved the company roughly $9 billion annually but angered GE investors. As the company's stock price dropped from $41.03 in October 2007 to $6.66 in February 2009, many investors and retirees found themselves with shrunken portfolios and dividends.

“I remember the day GE stock went to $6.66 on the screen,” Crosby says “I took a picture of it and said ‘there’s the devil’s number, right there.’ ”

A month later, in March of 2009, GE lost its triple-A credit rating from Standard & Poor’s followed by the same downgrade at other ratings agencies. GE had prided itself on its triple-A rating, using it as a sales point to customers and a sign of discipline and strength to investors and employees. It was defensive and angry when analysts or journalists in 2008 questioned why spreads in the bond market were indicating that the investment community was concerned about GE’s creditworthiness and wasn’t viewing the company’s bonds as triple-A quality.

“I got tired listening to Immelt,” Crosby said. “He cost a lot of people money.”

An activist hedge fund and GE’s latest crisis

Small investors such as Crosby and Labalme got creamed. Labalme normally earned roughly $69,440 each year in dividend income from his shares. But in 2008 and 2009, he experienced a cascade of bad fortune. As GE cut its shareholder dividend by 68 percent in the second half of 2009 to 10 cents per quarter, Labalme felt a major blow to his retirement plans. He saw his dividend income drop by $42,000 over the years of the financial crisis to $17,440.

"To me, GE, which I always admired, now means 'Go Elsewhere," Labalme told me in April of 2009, when GE announced its dividend cut. Later, as the company ended the dividend completely, Labalme’s GE dividend income dropped to zero.

“I’m semi-retired,” the lawyer, then 78, said. “But I’m probably going to have to go back to work now.” The decline and near collapse of GE not only shook his retirement plans; it shook his faith in American capitalism and American idealism.

By 2011, GE's market capitalization had dropped to about $195 billion from $298 billion in August 2008, before the financial crisis hit. The government treated GE as a “too big to fail” company alongside General Motors, Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan. Immelt’s team of lawyers and lobbyists in Washington sprang into action, meeting with the Obama administration and positioning GE as a helper to the president, rebuilding the country’s anguished economy. Immelt was appointed to Obama’s Economic Recovery Advisory Board and, later, to chair Obama’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness.

GE sidled up to Obama to gain access to government stimulus spending as its core industrial sales slumped during the financial crisis. GE estimated governments worldwide would invest $2 trillion in global infrastructure after the financial crisis and hoped it could gain sales from that stimulus.

“Some companies are treating the government's growing reach -- and ample purse -- as a giant opportunity, and are tailoring their strategies accordingly,” my then colleague Elizabeth Williamson and I reported on the front page of the The Wall Street Journal in 2009. “For GE, once a symbol of boom-time capitalism, the changed landscape has left it trawling for government dollars on four continents.”

Our reporting showed how Immelt, a lifelong Republican, convened a meeting of environmentalists in New York and told them, “We’re all Democrats now!” When The Journal published that exclamation in the opening of a page one story about Immelt’s pivot toward Democratic politics, I was told that he became irate on a private corporate Gulfstream V jet, slamming his fist on a table and cussing out his public relations staff.

Immelt cast himself as a sensitive human being, picked apart unfairly by the nasty business press. Later when he retired, that same business press, broke news that showed Immelt often flew with two corporate jets all around the world, a backup one in case his first one broke down.

Wall Street before Main Street

After the financial crisis of 2008-2011 passed, Immelt was back to his deal-making ways. He made $14 billion worth of acquisitions in oil and gas between 2007 and 2014, right before oil prices collapsed between 2014-2017. GE saw profits slide by 92 percent in its oil unit. His $10 billion acquisition in 2015 for French power generation giant Alstom happened right before natural gas prices slumped and caused 45 percent profit declines in GE’s power generation unit and led to 12,000 layoffs in 2018.

GE executives started talking like Stephen Hawking about the future of knowledge, the Internet of Things and of a Gattaca like industrial economy. Its marketing department waxed on about cloud-based internet software, data analytics and artificial intelligence tools such as machine learning. GE suggested it was creating the “industrial Internet” and called the software “Predix.”

The company ran expensive advertisements during the Oscars ceremony in 2016 that tried to poke fun at itself while showing how it was recruiting software talent and trying to keep up with the technology boom. The spots, created by ad agency BBDO New York for an undisclosed budget, featured a character named “Owen” who was recently hired by GE and is bombarded by other candidates who want to get a job there. The series was typical of GE’s self-aggrandizement.

The virtue of a premium global conglomerate, so Immelt often argued, was that it could survive downturns in one segment because other segments would be doing fine. But that didn’t seem true of GE in 2008 or in 2017. As its power division experienced losses of $3 billion alongside rivals such as Siemens AG and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd., GE suffered a domino effect.

In the past two decades, GE executives and board members have had myriad discussions about how large GE or GE Capital should become. "There was a belief that GE could handle additional growth and handle it well because of the managerial discipline and systems inside the company," said Robert Swieringa, then a GE board member and an accounting professor at Cornell University, during a phone interview with me in 2011. "Today, we might come to a different conclusion."

The counter theory is that legendary investor Warren Buffett led his conglomerate, Berkshire Hathaway, to appreciate by $430 billion since November of 1999 while GE lost $270 billion during that same time frame. Both of those companies were large, diversified conglomerates with assets in finance, energy, utilities, real estate, media and energy. They were both said to be proxies for the wider economy.

GE was a flashpoint for investor anger. My stories on GE at The Wall Street Journal would often see hundreds of readers ranting about Immelt and GE in the comments section. Their anger was palpable. “What’s wrong with GE?” was a typical water cooler question among investors from Wall Street to Main Street. And it wasn’t limited to small investors.

Activist investor Nelson Peltz started agitating against GE and Immelt in 2015. He spent $2.5 billion to buy a 1 percent stake in GE shares in October of 2015, placing his Trian Fund Management LP as one of the top 10 shareholders of GE.

Towards the end, there was so little activity in the former headquarters that GE employees took to describing the place as a “morgue.”

Seeking better tax breaks for its corporate headquarters, GE traded its squarish Fairfield, Conn., office complex in for a new $200 million, 2.5-acre headquarters in Boston in 2017 and dubbed it “GE Innovation Point.” Meanwhile, all around Fairfield, one could find McMansions owned by former GE executives with “For Sale” signs in the yard. Towards the end, there was so little activity in the former headquarters that GE employees took to describing the place as a “morgue.”

Immelt failed to fulfill many promises and ambitions. The company partially freed itself from the muck of 2007-2011 but was still so mired down that many of its worst fears came true in 2017-208. By August of 2017, GE’s stock price was once again in decline and Immelt stepped down as CEO, saying he would stay on as chairman until the end of the year. By October, however, he was off the board completely. Peltz’s pressure on GE sped up the transition from Immelt to its next CEO, John Flannery.

From bad to worse

On his first day as CEO on Aug. 1, 2017 at age 55, John Flannery wrote to the more than 300,000 GE employees promising that he would “always own up to what is going well and what is not.” Flannery was known as a sober-minded, egg-headed, operational fix-it guy inside GE. He spent 30 years at the company, mostly at GE Capital, and is credited with helping to turn around its healthcare division.

Flannery started moving and acting quickly. He pared back the lofty ambitions of GE Digital, cutting $400 million, or 25% of its budget and refocusing its efforts on a few applications. Immelt spent $49 billion on stock buybacks between 2014 to 2017. But as the company was short on cash, Flannery and the new regime cut dividends by 50% in November 2017 to preserve cash. (It was just the second time since the Great Depression the company cut its shareholder dividend.)

Flannery said the company wouldn’t pursue massive acquisitions and acknowledged that the Alstom deal “has clearly performed below our expectations.” He announced that GE would sell at least $20 billion worth of assets in the next two years and indicated “all options are on the table” and that there are “no sacred cows.” He streamlined accounting methods at the company, replaced the leadership of GE Power and oversaw a wider departure of board members and senior executives, attempting to cleanse the company of its blind spots, missteps and faulty paradigms.

Then, in January, a cascade of internal bombs went off. GE announced that it was taking a $6.2 billion charge and had to set aside another $15 billion over seven years to insure long-term care policies from North American Life and Health. GE hadn’t sold these products since 2006 but it turned out that underwriters and employees for that insurance portfolio wrote or backed wildly bad policies with wildly bad math. On Jan. 25, 2018, GE reported a huge quarterly loss of $9.8 billion and disclosed that the SEC was investigating some of its accounting practices. The news caused investors to worry about what else might be lurking on the balance sheet and which bomb might go off next.

In February of 2018, GE disclosed in its annual report that the Justice Department was likely to claim that GE’s WMC Mortgage, a subprime lender before the financial crisis, violated federal lending laws in 2006 and 2007. Although GE sold the WMC assets, GE was still responsible for WMC and its lending activities that included $65 billion of mortgage loans from 2006 and 2007. GE hadn’t yet paid fines for owning the subprime lender the way that other Wall Street banks paid billions in penalties. GE put the remnants of that business into bankruptcy in April and agreed to pay a $1.5 billion fine.

In late May of 2018, Flannery announced he would spin off GE’s railroad business in a deal valued at $11 billion, combining it with Wabtec Corp. a company in Wilmerding, Pa., that makes equipment for mass-transit and freight railways. Wabtec was formerly known as Westinghouse Air Brake Technologies Corporation and was once part of GE’s greatest rival, Westinghouse Corp., which itself fell into bankruptcy and closure in 1999.

A month later, on June 20, GE received the bad news that it was being dropped from the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the blue-chip index of 30 companies that is supposed to represent the U.S. economy. GE was booted in place of Walgreens Boots Alliance drugstore chain, perhaps a telling sign in a country addicted to pain killers and debating ways to regain its lost manufacturing economy. GE was the last of the original members of the Dow Jones industrial average from 1896 and executives often bragged about the company being an original member of the Dow 30.

Flannery’s new plan involved keeping just three major business units that accounted for 60 percent of GE’s $122 billion in revenue in 2017: jet engines, electric power generators and wind turbines. It seemed he was cutting the organization to the bone, looking for the new story and scope of GE. Flannery said he would also trim $500 million per year from corporate overhead costs and $2 billion of companywide expenses.

Nelson Peltz’s Trian, one of the activist investors on the inside that grabbed GE by the throat, expressed pleasure. Anne Tarbell, a Trian spokesperson, announced that the moves “will create substantial value for shareholders.”

In his March letter in the 2017 annual report, Flannery projected realism as a path to avoid a lights out scenario that befell GE’s rival, Westinghouse. He suggested GE should stop fighting and ignoring the critique of journalists, investors and analysts but, rather appreciate their examinations and demands for accountability. “Many people have lost faith in us. I have not,” he wrote. “As difficult as 2017 was for everyone connected with GE, it was also a chance to reflect on what this company means and why it exists.”

By October of 2018, Flannery was also gone. The board of GE handed the CEO job to their fellow board member, H. Lawrence “Larry” Culp Jr., who led Danaher Corp. from 2000 to 2014 and led that industrial company to growth during the same time frame GE was suffering.

GE’s share price rose nearly 8 percent in late June of 2017 to $13.74 after the healthcare and oil industry deals were announced. They have sunk back to $11 since then. Analysts view the way forward as a long, hard slog.

“We are doing everything in our power to return GE to a position of strength,” Culp wrote to investors in the 2018 annual letter. He champions GE’s industrial portfolio and technology along with the need for the company to trim its debt to create a more healthy, disciplined balance sheet.

Culp wrote that GE had become disconnected with customer needs in some parts of the world and noted that its hyper-ambitious culture had grown disconnected in places with performance not living up its blustery talk. He points to the company’s future residing partly in its research labs where 1,000 scientists work on doing what Thomas Edison championed: “finding out what the world needs and proceeding to invent it.”

An unwinding or a rewinding?

When Thomas Edison died on Oct. 18, 1931, at age 84 after battling a failing kidney, the New York Times ran 22 stories about his life and death. President Herbert Hoover asked citizens to mark their sorrow by turning off all electric lights in unison at 10 p.m. eastern time on the evening of Edison’s funeral. Electricity, Hoover said, “is in itself a monument to Mr. Edison’s genius.”

The National Broadcast Company and the Columbia Broadcast Company jointly aired an 8-minute tribute to Edison on the radio and also asked listeners to turn out their lights. Across the nation, movie theaters went dark, traffic lights blinked out, electric advertising on Broadway in New York City switched off. The nation paid this odd tribute to an eccentric man who had illuminated the world by his inventive streak from small labs on Menlo Park and West Orange, N.J.

The corporate monument to Edison’s legacy hasn’t seen its light go out for good quite yet. And GE faced major hurdles in its first 20 years and throughout its life span. It’s rebounded before.

Capitalism is a process rather than a profit and loss system. “Most people in business don’t like that process because it’s too competitive"

Russ Roberts, a widely followed economics commentator who is the John and Jean De Nault Research Fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, notes that capitalism is a process rather than a profit and loss system. “Most people in business don’t like that process because it’s too competitive,” he said. “They will always look for ways to make it less competitive. They will always look for ways to avoid the losses while getting to keep the profits.

GE leaders believed the gospel of modern managerial capitalism. They tried financial engineering using leverage and the time value of money equation ad infinitum. They tried using heft and scale and vertical integration to bigfoot their competition. They tried crony capitalism methods of nuzzling up to the government when times get tough. They tried mom and apple pie branding and expensive commercials featuring a Wizard of Oz theme.

“GE means nothing to American capitalism. No company does,” says Roberts. “Who cares that Ronald Reagan worked there?”

GE committed some of the deadly sins that companies, like individuals, need to be wary of because those sins lead to other failures. GE’s primary sins were those of pride, greed and gluttony. GE’s comeback probably lies in a combination of effective management (repenting from its sins and establishing heavenly virtues within the company) and, somehow, tapping new innovation the way Thomas Edison did in the early days to create products the customer wanted.

Private investor Crosby lost about $125,000 in the in 2009 on GE as the financial crisis deepened and started to expose deep fault lines within the storied industrial company. Some of his family members lost even more than that.

“I don’t want one share of GE. I really don’t,” Crosby says. “The last thing I ever bought with GE on it was a refrigerator.”

And, by the way, GE appliances sold in 2016 to Chinese appliance maker Haier, which has the right to use the GE brand name until 2056.