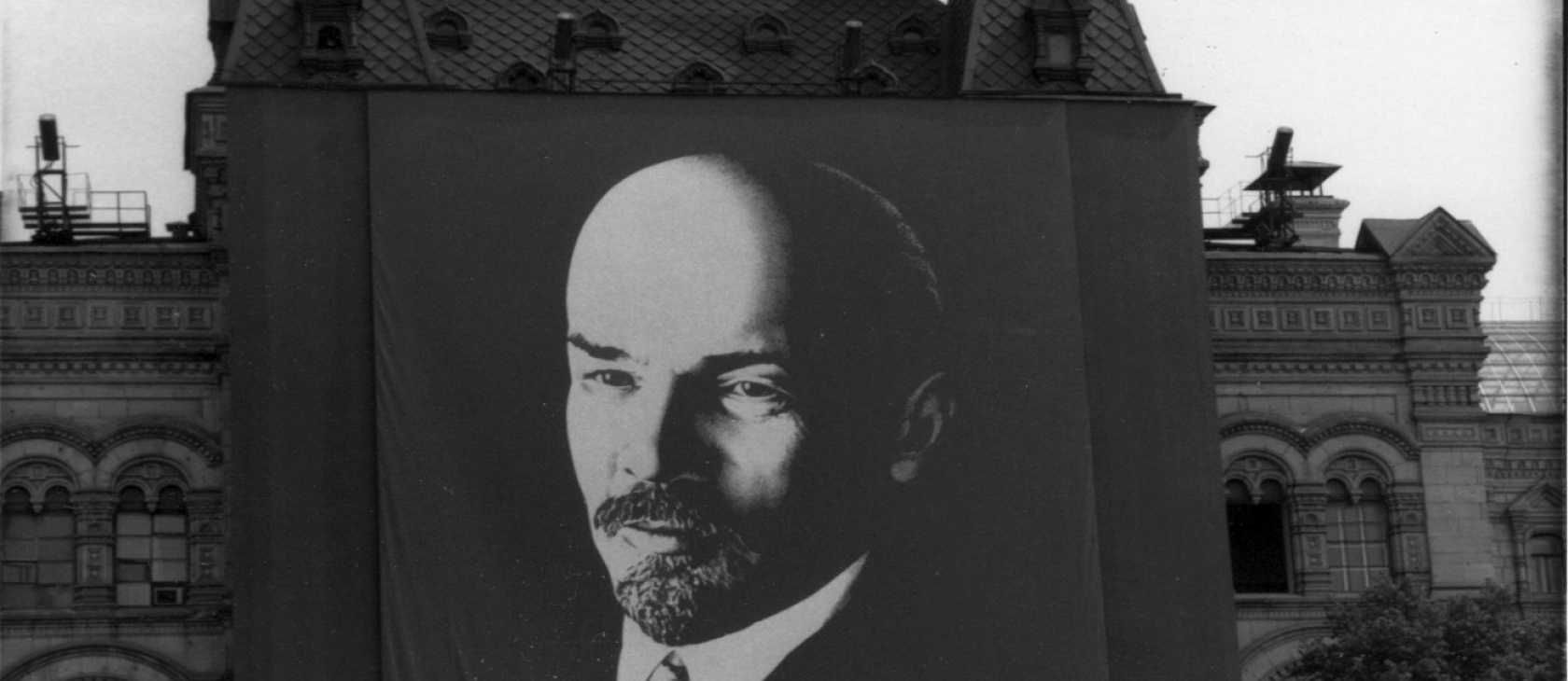

In an article published today at The American Spectator, Acton Senior Editor Rev. Ben Johnson comments on the solemn centenary of the Russian communist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin’s ascendancy to power. Rev. Johnson notes the Russian Orthodox Church’s distaste for the symbolism of the late dictator's body being prominently displayed in the Kremlin:

These century-old events continue to dominate the news in modern-day Russia, where leaders grapple with how to deal with one tangible legacy of the Marxist past: After his death in 1924 at the age of 53, Lenin’s corpse became the centerpiece of a gargantuan, pyramid-shaped mausoleum in Red Square, where he still lies in artificially preserved repose. Today, many would like his body, and his legacy, buried.

Christian leaders in the United States kicked off the latest row in a March 10 encyclical signed by the bishops of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR) about the solemn centenary. “We must not under any circumstances justify the actions of those responsible for the deadly revolution,” they wrote. “A symbol of reconciliation of the Russian nation with the Lord would be to rid Red Square of the remains of the main persecutor and executioner of the 20th century, and the destruction of monuments to him.”

Their words echo some inside Russia. The Elder Iliy (Nozdrin) of the historic Optina monastery, the confessor of Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia, called Lenin “a villain of villains” who “should have been long ago thrown out of the mausoleum. Through him the Lord does not grant us the full development of our Fatherland.” (Patriarch Kirill, while sympathetic, has been non-committal.) The priest of the Kazan Cathedral in Red Square, which looks down on Lenin’s tomb both literally and metaphysically, said the mummified presence “is a kind of brake on the movement of the country forward.”

Johnson notes that these Russian condemnations of Lenin see not only the preservation of his mausoleum as a bane to Red Square but, ultimately, all of Russia. They are not alone in their distaste, as there is a growing consensus for the dumping of Lenin’s body:

Burying the Bolshevik leader enjoys the support of the Chief Rabbi of Moscow, Berel Lazar, as well as multiple factions within the Duma, and a sturdy majority of citizens, according to numerous polls.

The big question mark is Vladimir Putin, who has sent a series of conflicting messages on the topic. In 2001, he opposed the burial for fear it would tell too many Russians that “they have worshipped false values.” In subsequent years, his close advisors Georgy Poltavchenko (a former KGB officer) and Vladimir Medinsky publicly raised the prospects of burial, apparently with Putin’s support. …

If Orthodox Christians are eager to bury Lenin, it is less an act of spite than of reciprocation. His decree of October 26, 1917 — one of the first acts of the atheistic Bolshevik regime — ordered the seizure of all church and monastic property for redistribution to “the whole people.” The great famine of 1921-22 — which killed five million people due, in part, to his collectivization of farm land during the time of “war communism” — would give him the excuse he needed.

In his conclusion, Rev. Johnson articulates that while the economic cost of preserving Lenin’s body can be calculated, the potential damage caused by the enshrinement of Lenin is incalculable. The errors of communism have had a profoundly negative effect on Russian history and so the burying of Lenin is not just the burying of a man, but the symbolic action of burying the Marxist ideals associated with Lenin:

Today, the economic cost to the Russian people of preserving Lenin’s ghoulish remains can be precisely denominated: 13 million rubles. Taxpayers spent that amount (approximately $198,000) last year to carry out the “biomedical work” to preserve “Lenin’s body as it looked in life.” His tomb is closed until April 16, as Lenin’s body undergoes two months of submersions in chemical solutions including formaldehyde, potassium acetate, hydrogen peroxide, and acetic acid solution, followed by injections to keep his cadaver looking supple.

The potential harm caused by Lenin’s continuing enshrinement, however, is incalculable. A 2015 psychological study found that nationally recognized heroes “may help people to understand the norms and values within society.” Lenin’s mausoleum serves, fittingly, as a perverse incentive for emulation.

There is precedent for Lenin’s removal from its place of honor. Josef Stalin’s remains were displayed next to Lenin’s from his death in 1953 until 1961, when Nikita Khrushchev ruled the arrangement “inappropriate.” Stalin is now buried in the Kremlin wall.

William Faulkner wrote — appropriately enough, in Requiem for a Nun — that “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.” But in this case, the detritus of a nation’s past can — and should — be buried in ignominy, denying Communism the capacity for a resurrection that it so fiercely denied.

To read the full article, click here.

(Photo credit: Seth Morabito. This photo has been cropped and modified for size. CC BY-SA 2.0.)