Developed nations are reconsidering the economic and moral impact of the inheritance tax. This is a welcome development, since a large estate tax has broader negative consequences for individuals, families, and businesses, as illustrated by my native Spain.

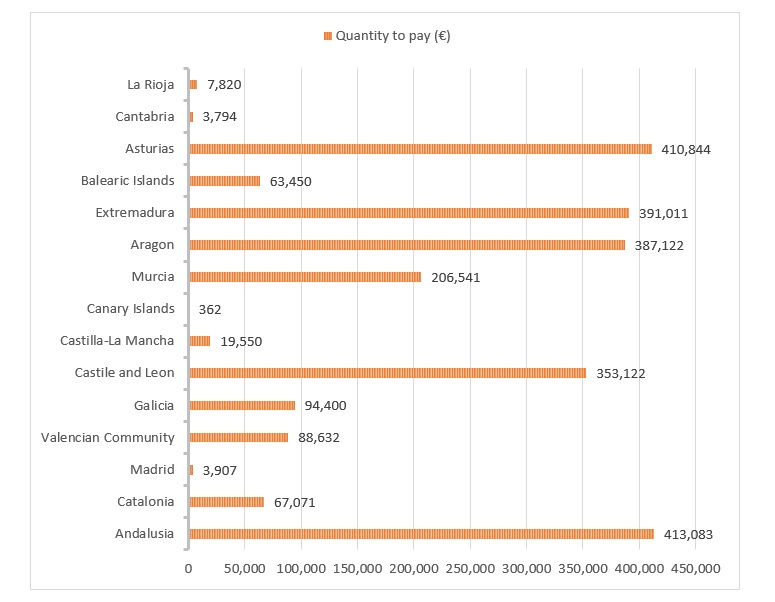

Spain has one of the highest inheritance tax rates in the OECD, charging up to 34 percent of an estate upon someone’s death. However, this management is decentralized, with those taxes managed by autonomous regional governments. (Navarre and Basque Country have their own fiscal regimes.) This has led to notable differences among the different regions. The Expansión newspaper analyzed the case of a 30-year-old single person who receives an inheritance of €1.5 million.

In the majority of regions, an estate comes with a high cost. As a result, since the economic crisis began 10 years ago, more than 200,000 families have renounced inheritances in Spain. In 2007, there were only 11,048 renunciations. Moreover, since some families have lost their homes. (See, for example, this dramatic case in Seville.)

The tax puts the continuity of family-owned businesses at risk. Furthermore, it part of the patchwork of economic interventions that discourage the formation of businesses nationwide. According to the 2016-2017 edition of the "Global Competitiveness Index" of the World Economic Forum, high tax rates top the list of the “most problematic factors for doing business” in Spain. Such tax rates are followed by overly burdensome regulations, inefficient government bureaucracy, and restrictive labor regulations.

The nation’s particularly harsh inheritance tax policies made international headlines in September 2014, when the European Court of Justice struck down its policy of charging higher taxes of non-residents. German, Irish, and British tourists who spend their holidays on the Mediterranean coast (for example, in Benidorm and Mallorca) are one of the main categories of non-residents affected by this discrimination. However, it impacted the substantial number of Spanish expatriates, as well.

Meanwhile, the state always holds out the possibility that it could inherit an estate and disperse its funds, if it feels the need to do so based on its preferred “social function.” Article 33 of Spanish Constitution says that the right to private property and inheritance “shall be determined by the social function which they fulfill.” (According to the article 956 of Spanish Civil Code, “in the absence of persons entitled to inherit, in accordance with the provisions of the preceding Sections, the State shall inherit.”)

Spain, an outlier?

The world seems to be moving away from this standard. Six EU countries – Portugal, Slovakia, Sweden, Austria, Lichtenstein, and the Czech Republic – have already repealed the inheritance tax since 2000, according to the Tax Foundation. President Donald Trump supports such a change to U.S. policy.

Curiously, one of those countries where this tax has already been repealed is Sweden, used as an example of socialist policies worldwide, including by Spanish left-wing parties. (The far-left Podemos, or PSOE, cites Finland as its model, instead of Venezuela.)

Families should not be forced to sacrifice their property in order to sustain an expensive state.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban said last May 23 that “there is no inheritance tax in Hungary" - for a specific reason. "There was communism here for 40 years. Family assets were confiscated, and there was nothing left.” Sadly, unrelated heirs cannot enjoy the exemption applied in 2006 by Prime Minister Gyurcsany’s government. (Ferenc Gyurcsány, a former socialist, left that party to form the Democratic Coalition in 2011.)

In Spain, fierce social indignation has brewed against this tax, intensifying this year. There have been mass protests in the regions with the highest rates (for example, in Asturias, Aragón, Andalusia, and Extremadura). Civil society has also organized and created associations to oppose this tax.

One of these groups, Stop Sucesiones, has registered a decree-law proposal in the regional parliaments of Andalusia, Extremadura, Murcia, Aragon, and Asturias. It aims to protect the family heritage by greatly reducing the taxes levied on estates left by parents to their children, applying this relief retroactively for the last four years, and reforming the use of sine die procedures.

Thus far, no Spanish regional government has decided to repeal the estate tax. At the national level, there is little apparent political debate. But in July, some experts in fiscal affairs suggested that the minister of the Treasury, Cristobal Montoro (a member of the People’s Party), harmonize that tax nationwide. The Socialist Party and Podemos support the same policy out of concern over “fiscal dumping” – which, one publication explains, “means attracting wealth to the community to benefit from its taxation.”

Nevertheless, “being wary” of fiscal competition between regions should not be part of leftists’ concern. Portugal’s center-right government repealed the inheritance tax in 2004 (although it maintains a 10 percent stamp duty except for spouses and children). The Spanish provinces of Badajoz, Caceres, Huelva, Leon, Salamanca, and Zamora would find themselves in “competition” with Portugal, rather than other provinces.

Related problems

Leftists express skepticism towards repealing the inheritance tax out of concern over funding welfare services (“free” health and education, hiring more doctors, teachers, and nurses, etc.) and subsidies (unemployment, widow’s pension, basic/minimal income, providing public transportation tickets for the elderly, etc.). These, too, discourage business.

Socialist bureaucrats must not undermine principles of social solidarity and subsidiarity.

Note the connection between public welfare spending and the inheritance tax in two states with the highest estate tax rates: Extremadura and Andalusia. Both of them are the least economically free regions of Spain, according to the "Índice de Libertad Económica" (“Economic Freedom Index”) produced by the Spanish pro-market think tank Civismo.

A report from the Consejo Económico y Social (“Economic and Social Council” in Spanish) found Extremadura and Andalusia have the highest percent of GDP dedicated to public administration (25.9 and 20.5 percent respectively, both significantly higher than the national average of 17 percent). Over the decades, they have been ruled by the Socialist Party. (Between 2011 and 2015, the People’s Part ruled Extremadura, but without enacting significant reforms.)

Extremadura is poorer than some Central and Eastern European regions, according to a report released by the El Club de los Viernes (“The Friday Club”), a Spanish classical-liberal think tank. Moreover, since 2014, Extremadura has been overtaken by Estonia, one of the freest economies in Europe alongside Ireland. Both Spanish regions are also continental and national leaders in unemployment.

The inheritance tax is immoral, not only because its original Spanish form violated European legal norms and procedures. It forces children to pay taxes, for a second time, on the fruit of their relatives’ or loves ones’ labor. Those loved ones already paid tax on this income during their lives; now the state will charge another person a separate tax on the same income. Nor should the state so freely inherit and dispose of estates as politicians, rather than their earners, see fit. It is not right to use their hard work to benefit politicians or convert the state into a real estate agency.

Families should not be forced to sacrifice their property in order to sustain an expensive state. Entrepreneurs and businessmen are the ones who created this prosperity. Socialist bureaucrats must not undermine principles of social solidarity and subsidiarity.

(Photo credit: Nick Youngson. This picture has been modified for size. CC BY-SA 3.0.)