Daffyd Thomas, one of the most memorable characters in the ‘Little Britain’ series, is ‘the only gay in the village’. Or so he likes to think. Daffyd loves the role of the outsider, who bravely defies society’s stifling conventions. So he convinces himself that everybody is shocked and horrified about the fact that he is gay. But he has to work hard to sustain this delusion, because everyone he meets is either indifferent, supportive or gay themselves.

If Daffyd were a real person, he would probably write for the Guardian. Guardian journalists have this irritating habit of espousing fashionable views while adopting a bet-my-radicalism-shocks-you tone.

A recent example is this Guardian article, by Ellie Mae O’Hagan, on Marx and McDonnell:

Ladies and gentlemen, it’s time to clutch your privately owned pearls, for the shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, has had the audacity to acknowledge – live on TV, no less – that there is a lot to learn from Karl Marx. Judging by the horrified reaction McDonnell’s comments unleashed, you’d think he had ridden into BBC studios on a Soviet tank […] If these histrionics are anything to go by, the respectable position must be that Marx’s ideas are outdated and dangerous, and that we should all carry on as though they never existed.

First, that’s not really what happened. Yes, there was a little storm in a teacup around a McDonnell interview about a week ago, which lasted for about a day – but that was mostly about McDonnell’s inconsistency rather than his praise of Marx; it was about the fact that he sometimes says he is a Marxist, and sometimes says he’s not.

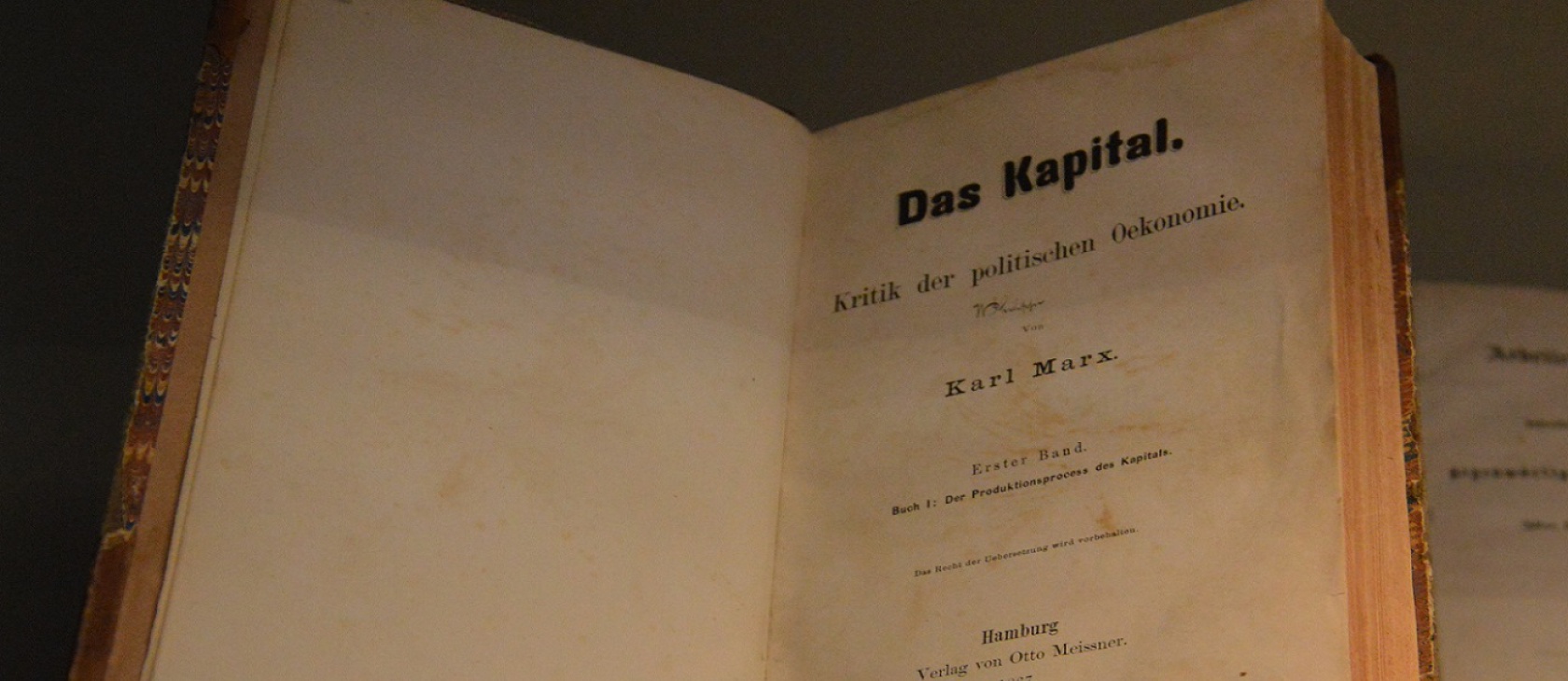

Be that as it may: The claim that there’s a lot to be learned from reading Das Kapital is not quite the brilliant heresy that O’Hagan seems to think it is. It’s a well-worn cliché. I’ve heard it a million times. And my problem with it is that whenever I ask people who make the claim what exactly they have learned from reading Das Kapital, the answer is either awkward silence or some vague generality. (“Well there’s, like, recurring crises in capitalism. Isn’t that, sort of, what Marx said?”)

Sure, the fact that it’s a cliché does not make it wrong. Clichés are usually true. And yes, of course you can appreciate Marx without sharing his conclusions. In fact, there are even classical liberals and libertarians who are quite fond of Marx.

But I’m not convinced by O’Hagan’s claim that “we can’t understand capitalism without considering Marx.” Yes, Marx wrote a lot about economic crises. But that does not mean that every economic downturn proves Marx right. Nostradamus wrote a lot about catastrophes, but that does not mean that every natural disaster, which vaguely resembles something Nostradamus has written, proves Nostradamus right. Hundreds of economists after Marx have written about economic crises as well, and there are now dozens of competing business cycle theories. If every economic downturn proves Marx right, it must also prove Henry George right. And Milton Friedman. And Ludwig von Mises. And John Maynard Keynes. And Simon Kuznets. And many more.

Except they cannot all simultaneously be right, because some of these theories are mutually exclusive. Marx, of course, did not just have ordinary business cycle fluctuations in mind. He predicted that recessions would get more severe over time, ultimately contributing to capitalism’s self-destruction. That clearly has not happened. Whatever his other merits may be, he was wrong on the grand narrative. So, why give him the benefit of the doubt?

I’m not claiming to a Marx expert; quite the opposite. A few years ago, I was invited to a panel discussion on Marxism, to debate against some Marxist professor. I chickened out, and I would chicken out again if I received another invitation of that kind today. I know that my opponent would say something like “You clearly have never read the key paragraph on page 857 of Das Kapital, otherwise you would know X, Y and Z,” and they would be right. I haven’t read page 857 of Das Kapital. I haven’t even read page 1. I only have second-hand knowledge of Marx, which I picked up by reading other economists who refer to him.

But what I’m saying is: The burden of proof should be on those who insist that Marx is still relevant, and that we cannot understand capitalism without him. It should not be on those who believe that Marx has been broadly refuted by events, and that reading Das Kapital is a waste of time. The people who urge us to read Das Kapital may well be right – but their case is not nearly as obvious as they think it is, and reading Marx has opportunity costs.

If I was stranded on a lonely island, with only a copy of Das Kapital, then yes, I would read it. But as things stand, there are many excellent contemporary economists who I haven’t read yet, plus people who aren’t technically economists, but whose work has important implications for economics (in areas like psychology and cognitive science). It’s not enough for the Marx fans to claim that there’s "a lot" to be learned from reading Marx. I’m sure there is. But there’s a lot to be learned from many other, more contemporary authors, as well. And I can’t see which of them I should put on hold to read Marx instead.

This article originally appeared on the blog of the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) and is reprinted with permission.