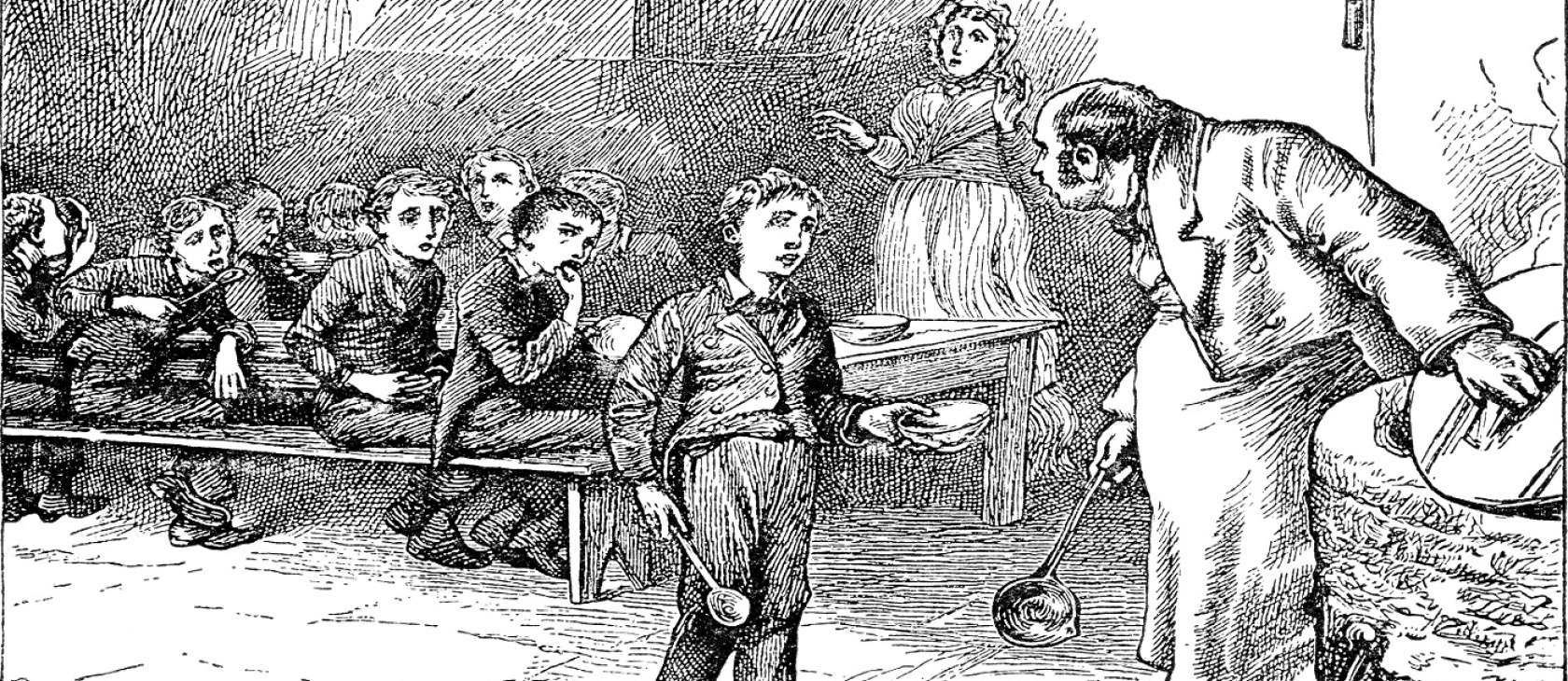

Charles Dickens wrote in Oliver Twist that “very sage, very deep” British leaders “established the rule that all poor people should have the alternative … of being starved by a gradual process in the [poor]house, or by a quick one out of it.” If one were to believe a recent UN report on poverty, the fate of the poor remains Dickensian.

Or rather, Hobbesian, as UN Special Rapporteur Philip Alston quoted the philosopher’s ubiquitous description of life as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” in his preliminary statement on British poverty.

Yet Alston misrepresented the extent and depths of poverty and misdiagnosed its causes, while dismissing the most proven antidote to child poverty.

Confusing poverty with inequality and anecdotes with data

The UK follows much of Europe in measuring income inequality, which it defines as poverty; specifically, anyone making less than 60 percent of the median income is considered “poor.” In fact, Alston derided the notion the very notion of “so called ‘absolute poverty.’”

But the emphasis on relative equality leads to strange results. Alston reprimanded the UK while praising Mauritania for making “significant progress in alleviating poverty,” although 42 percent of the latter nation lives on less than £1,000 a year.

Alston belittled the May government’s contention “that there is no extreme poverty in the UK, and nothing like the levels of destitution seen in other countries.” He then proceeded to quote a number of personal stories shared with him at food banks.

But the plural of anecdote is not data and, as Nobel-winning economist Paul Samuelson wrote in Newsweek in 1967, “Anecdotes do not constitute social science.”

What really matters is the average family’s ability to afford necessities, and the verifiable facts paint a much different picture.

A mere six percent of people said they find it “quite or very difficult to get by financially” – less than half the number who reported being hard-pressed in 2012 – according to the Office of National Statistics (ONS). As median household incomes have exceeded their pre-recession highs, the percentage of people satisfied with their household income has spiked since 2002.

Furthermore, Alston “ignores key evidence from the ONS which shows incomes actually increased for the lowest income quintile over the period 2008 to 2017,” writes Richard Norrie at the London-based Institute of Economic Affairs.

Given real problems in places like sub-Saharan Africa – where Alston’s office typically focuses – why was he in the UK at all?

Associating austerity and Brexit with poverty

Alston said he made his office’s fourth visit to a developed Western country in part because he wanted his study to help Brits “better understand the implications of an austerity approach,” which emphasizes cutting social spending.

“Poverty is a political choice” Alston said. “Austerity could easily have spared the poor … but the political choice was made to fund tax cuts for the wealthy instead.”

But tax cuts are not an “expenditure.” (They merely allow people to keep more of the money they earned.) The bemoaned “austerity” was never terribly austere, and Chancellor Philip Hammond’s most recent budget boosted spending by £32 billion over last year.

Furthermore, he felt Brexit – the UK’s exit from a supranational government – created an opportune time for the UN to intervene. His statement warns that “fears and insecurity” fueled the Brexit vote. Leaving the EU will contract the economy by as much as eight percent, and “the poor will be substantially less well off than they already are.”

In reality, the UK’s economy outperformed expectations. Economic growth hit a two-year high this year. The greatest threat to the market is uncertainty which is caused, in large part, by the doubtful future facing the Brexit-light deal offered by Theresa May.

The government rightly assessed the “extraordinary political nature” of the report as “wholly inappropriate.”

Dismissing the poverty cure

Alston chided the UK government for highlighting the fact that unemployment has reached a 40-year low, because “being in employment does not magically overcome poverty.”

However, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) – far from a Conservative Party institution – noted in a study last year that “the rate of persistent poverty for children in households that have had someone in work in each of the last four years is just 5% … On the other hand, children in households that have had no one in work for at least three of the last four years account for slightly over 40%.”

Put another way, employment is the most effective way to reduce child poverty, Alston’s purported concern.

The only persistently depressing metric in the panoply of data offered by the ONS is the stubborn percentage of young Britons classified as NEETs: those in their prime working years who are Not in Education, Employment or Training.

The message they most need is not another political jeremiad blaming their problems on politicians who are too stingy with other people’s money. Young people at risk need to hear that unlocking their potential could change their lives, their communities, and possibly the world for the better.

The Catholic mystic Catherine of Siena once advised a young man, “If you are what you ought to be, you will set fire to all Italy.” The talents latent in every human heart can illumine every nation in the world.

If only Alston had delivered such a hope-filled message to children of God who find themselves sidelined in their own lives.