Until September 8, 1609, Juan de Mariana did not appear to have been fully aware of just how risky it can be to participate publicly in an ideological debate, especially when one places the pillar of private property at the center of one’s political and economic theory. On that day a group of armed men headed by one Miguel de Múgica broke into the Jesuit monastery at Toledo and carried out an arrest warrant against him by order of the Bishop of the Canary Islands, Francisco de Sosa (a Franciscan), whom the King had nominated to adjudicate the controversy over the inconvenient philosopher. Three days prior, a group of officials from the Inquisition had appeared at his chamber and taken him off to make a deposition before that body’s examiners (Ballesteros, 1944, p. 222). It was then that Mariana had acknowledged being the author of his latest book, a volume of seven essays, and indicated surprise that his words had caused so much commotion.

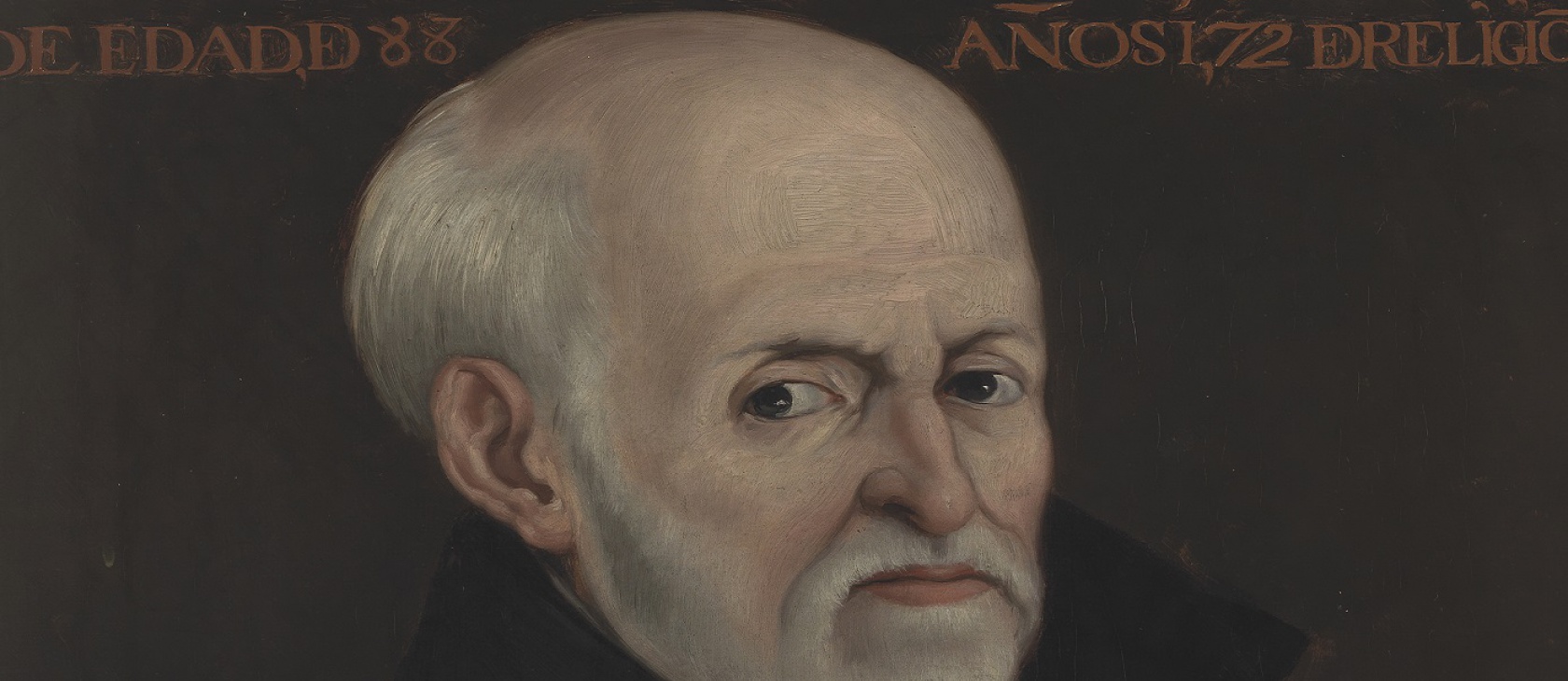

The life of this man from Talavera had always been beset by momentous challenges. Some, such as the composition and publication of the first History of Spain, he had brought about quite consciously in order to highlight certain lacunas which he felt the society in which he lived needed to address. Others, however, were imposed upon him as a consequence of complex events which he had never intended to unleash. Seventy-three years before his arrest, towards the end of summer, a few days after his birth in Talavera de la Reina, he had to be transferred by protectors into a new home in another town, a place where the good name of his father, Juan Martínez de Mariana, the local dean of Talavera, could remain free from any dishonor.

The brilliance of Mariana’s intellect, complemented by his natural facility for languages and his portentous memory, meant that Ignacio de Loyola, always on the lookout for talent, would focus his attention on him during his first year of studying theology at Cardinal Cisneros’s Complutense University at Alcalá de Henares. The year was 1553, and he would officially enter the Jesuit Order the following January, along with other future literati like Luis de Molina and Pedro Rivadeneyra (Ballesteros, 1944, p. 18).

After his novitiate, which he fulfilled at the Castle of Simancas, and having completed his studies at Alcalá, his superiors were anxious to take full advantage of his intelligence, especially his capacity for communicating and his command of Greek and Latin, at which he continued to excel with each passing year. And so it was that Mariana was given the mission of teaching theology in the foreign capitals where the Company of Jesus sought to extend its reach. First, he was tapped to go to Rome, where in 1561 he began teaching theology at Loyola’s new Colegio Romano, attended by exceptional students, such as the future Cardinal Robert Bellarmine. Between our Talaveran and the nephew of Pope Marcellus II there arose a friendship that would last their entire lives (Ballesteros, 1944, p. 247). After four years in the Eternal City, Mariana left, first for Loreto, and two years later he packed his bags again for Sicily.

In 1569, with eight years of teaching under his belt, Mariana left Italy to begin a new phase in his life as a teacher and scholar at the Sorbonne in Paris. There he received his doctorate and became a chaired professor of theology. His courses on Thomism soon made him one of the students’ favorite professors and won him international acclaim. His great gifts as an orator and his profound knowledge of the material meant that attending his courses became a matter of punctuality, for to arrive late typically meant not being able to find a seat for the Spaniard’s lectures.

On August 24, 1572, after more than five hundred nights of relative tranquility in Paris, Mariana likely awoke with alarm at the noise of the bells of the Church of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois. It was the beginning of the Saint Bartholomew’s Day massacre, which marked the bloody end to the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Mariana was made eyewitness to the deaths of thousands of Huguenots at the hands of their Catholic rivals. The use of religion for political ends and a murderous rampage resulting in the deaths of some 2,000 citizens of the capital, and between 5,000 and 10,000 in the rest of France, must have had a profound effect on the Thomist teacher, and years later they surely influenced his political philosophy, especially his thoughts on the limits of political power and his defense of tyrannicide.

After five years teaching in Paris, Mariana presented his resignation and asked to return to Spain. The Company of Jesus accepted his petition and that same year of 1574, after thirteen years abroad, the Talaveran arrived back in his native land. His voyage took him by way of Flanders, with a stop in Amsterdam. It is possible that his return to Spain was motivated by poor health. It might also be that he had decided to seek a certain tranquility that he could not find amidst the pupils of Paris, in the hopes of recording the thoughts that had occurred to him during so many years of meticulous academic study. Perhaps these two reasons mutually reinforced each other in the decision to come home.

That same year of 1574 he would also arrive for the first time in Toledo, where he would reside for the remainder of his life. Leaving behind the bustle of two great European capitals, Mariana now had within his grasp a long desired period of rest and calm. In his request to return to Spain he had asked to be allowed to dedicate himself to his ecclesiastic vocation and to preach, and once again his wishes had been approved by Jesuit authorities. In this way, Mariana chose of his own free will to abandon the life of a university teacher.

Nevertheless, this tranquility lasted but a short while. Still in 1574, the Inquisition commissioned him, against his wishes, to be the censor of the Polyglot Bible assembled by Benito Arias Montano, who had been charged with heresy for consulting Judaic and Protestant texts for his edition. The choice of Mariana as censor was logical from the point of view of the knowledge necessary to elaborate a well-founded decision. It certainly would have been difficult to find another person with sufficient command of the theology and languages essential to the task at hand. But it also followed a certain strategic and political logic. For the fact that Mariana was a Jesuit must have made the Inquisition believe that he would harshly censor and sanction Montano in his report. In August of 1579 he finished his work, surprising all involved and society in general with an extensive and detailed study that analyzed several errors but ultimately absolved Montano. The final decision regarding the Polyglot Bible, which took Mariana more than five years to reach, not only laid out the doctrine according to which Catholic exegesis can make rightful use of rabbinical texts, but was also the first indication of an independent attitude, which, although it meant a range of inconveniences at the time for those in search of political privilege, it would also be a source of great moral support for subsequent generations and, as we shall see, for many of his contemporaries.

That intellectual independence and that demonstration of multidisciplinary knowledge which Mariana revealed in his role as censor had an unforeseen effect, one which surely did not please him. For from that moment on, and for many years to come, Mariana would be besieged with Inquisitional assignments.

During the years that the astute theologian was finishing his evaluation of the Polyglot Bible, he began to dedicate himself to researching and assembling diverse episodes for his History of Spain. He worked for seven years on this titanic project. The History of Spain was by no means the first work he had undertaken, but it was the first that he had chosen of his own volition. Mariana had decided to fill an enormous vacuum in the culture of his country, and in his chamber in Toledo he worked nonstop to make it happen. Finally, in June of 1586, he finished the initial version of the History of Spain, which for more than two and half centuries would be no less than the definitive History of Spain, with multiple editions in both Latin and Spanish.

Owing to a plodding bureaucracy that was already substantial in those days, Historiae de rebus Hispaniae, which is the title Mariana gave to the Latin edition, would not circulate for another seven years, its publication thus coinciding with the centennial of the discovery of America and the Reconquest of Granada, the very episode with which Mariana opted to end his opus.

In 1585, a year prior to finishing the History of Spain, one of his best friends, García de Loaysa, was named the personal tutor of Prince Philip, the son of Philip II. Loaysa relied upon the intellect and the independent judgment of his friend when deciding on the knowledge that he was to impart to the future King of Spain. From then on Mariana served as advisor to Loaysa, and together they maintained a running correspondence regarding the education of the Prince, allowing Mariana to perceive the outlines of a new project, the elaboration of which he undertook of his own initiative. Five years later he had copious notes that would serve him in his work on monarchy. In the summer of 1590 he spent a period in a country house in El Piélago with two friends, sharing with them, chapter by chapter, the entire book with the aim of debating it and polishing it into its final form. The following year the text was essentially finished, but Mariana did not consider it appropriate for publication until after the death of Philip II and the rise to power of the actual Prince to whom he had directed the lessons in which his own political philosophy found formal expression. Standing out among the numerous themes that he analyzed are the genesis of human society, the origin and the essence of political power, the rights of human beings, and the importance of public finance. Among the conclusions that have caused the most sensation, over the course of the more than four centuries that have passed since its writing, are topics such as the anteriority of individual rights to the birth of political power, the subordinated condition of the king, the necessity and advisability of establishing clear limits to the exercise of a constrained power located in the king’s person, the right of individuals to kill a king who has resorted to tyranny, the illegitimacy of establishing a monopoly over military power, the usurping character of laws established without the consent of the people, the importance of maintaining a balanced budget, and the unjustifiable recourse to unlawful practices even for the attainment of the most noble ends.

Coincidental to the analysis he performed in the writing of the chapter on taxation, Mariana began to be intrigued by monetary issues, in particular the relation between money and the important matter of weights and measures. This interest in arduous numismatic and pecuniary topics led him to begin to conduct research toward yet another publication. Around 1590 he commenced a search for texts with which to increase his knowledge on these subjects.

With the change in monarchs upon the death of Philip II in 1598, the Talaveran decided to brush off his book on the education of the prince and attempt its publication. At the same time, he tried to publish De ponderibus et mensuris, the work that had resulted from his investigations of weights and measures, and money in particular. The censor praised De rege et regis institutione, and that same year both De rege and De ponderibus went to press, even though neither would be distributed until 1599. The same year his friend Loaysa died, having been named Archbishop of Toledo just a year earlier and having again taken Mariana as his advisor for his new position. The publication of De ponderibus et mensuris in 1599 represented the first work by Mariana which focused on monetary issues. In all there appeared three monetary texts which would eventually conduct Mariana into the shadows of captivity. Nevertheless, the general and eminently formal approach of the first of these did not yet suggest the problems that the Jesuit scholar would suffer as a result of his later economic theory. In fact, it appears that Mariana himself never even intended to pen anything more on the money issue.

On December 31, 1596, Philip II approved a royal decree by which he attempted to raise funds and escape the consequences of the umpteenth bankruptcy of the public coffers, which had taken place earlier that same year. That edict stipulated that the billon coins produced by the new hydraulic machine at Segovia were to contain no silver. The benefit this maneuver had on the Treasury was substantial. On the one hand, the King now issued coins made with the metal that had the least intrinsic value, and, on the other hand, he took advantage of the opportunity to order a recall of all billon coins previously put into circulation in order to extract their silver content and re-stamp them at Segovia with the same face value as before. The measure was not the slightest bit appreciated by the public and resulted in protests. In response to the social unrest, in 1597, the King, perhaps trying to live up to his nickname “Philip the Prudent,” decided to concede and added a grain of silver to each mark of copper in all subsequent issuances.

With the rise to power of Philip III and his advisor, the Duke of Lerma, monetary policy went down a path which we would today term “inflationary.” The five first years of his reign were characterized by a return to the minting of low-grade billon coins or coins with no silver content at all as per the late schemes of his father. In 1602, however, there was a qualitative change in this policy. On July 13, 1602, the Crown decreed the final elimination of silver and simultaneously reduced the coins to half their former size and weight. Given that the new silver-less and lower weighted billon coins maintained their previous face value, in spite of having their weight and size reduced by half, the coins minted previous to the new law suddenly and without warning saw their monetary value double. As one would expect, nobody wanted to turn over their old money in exchange for the new. Thus, on September 18, 1603, it was decreed that all coins minted previous to the new law had to be re-stamped. Accordingly, the coins with a value of two maravedís were now punched with four bars, signifying the duplication of their nominal value, and the same happened with the four maravedís coins, which had “VIII” imprinted over their previous value. In concert with these re-stampings, the treasurers subtly issued new coins officially valued at one, two, four, and eight maravedís, all of them without silver and in accordance with the new weighting system.

This measure allowed the King to collect the old maravedís coins (those with silver as well as those with relatively more copper), re-stamp them, and then pay off his suppliers and creditors using the coins with less metal. The value of the public treasury jumped by 66 percent (Ballesteros, 1944, p. 199). Some studies estimate the King’s windfall via this nifty trick at 875 million maravedís. Given the fact that the act of re-stamping does not generate any real wealth in and of itself, the proceeds that the King obtained had to result, naturally, in an equivalent diminution of the wealth of the citizenry, excepting those individuals and institutions that collaborated with the Crown in putting the new monetary policy into action and who thereby participated in the windfall.

The vast majority of the population was impoverished and commerce itself was adversely affected by the fiscal chaos, all of which heavily impacted the lower classes and the nation at large. Discontent spread, but the Palace walls seemed deaf to the lamentations of the people. Mariana, who always had a keen sense of morality and justice, immediately set himself to work on an explication of phenomena similar to those playing out in our own day, and he ended up denouncing the political authorities as those ultimately responsible for the situation.

What is certain is that very few people could understand as well as Mariana did the corrosive effects of suddenly changing by decree the weights and measures of money. The investigation that he had carried out while writing De ponderibus et mensuris had helped him to develop an understanding of the importance of always respecting said weights and measures. His historical knowledge offered him multiple examples from the past of the consequences provoked by similar monetary manipulations. What is more, his daily contact with commoners in the streets allowed him to directly assess the theoretical effects of such manipulations. Finally, his theological knowledge and his clear moral vision placed him in a unique position, allowing him to indicate those destructive consequences of the new monetary policy that lay in wait above and beyond its merely material effects.

And so it was that in 1603 Mariana undertook a new philological project on money. This time he focused on the causes and effects of monetary manipulations conducted by the politically powerful. This is the origin of De monetae mutatione as well as his own loss of liberty in 1609. In the words of Manuel Ballesteros Gaibrois, the events of 1602–1603 underscored “the tribune that lay dormant in the man, who converts his chamber into a jumble of written pamphlets and scientific experiments, and gradually conceives of a study—which will be entitled De mutatione monetae” (pp. 199–200). It is not clear whether or not Mariana initially imagined this project as an independent treatise on money. If this was the case, he probably thought that the topic was of such importance that he could not wait to see it published along with the rest of the essays that he had already finished or else was in the process of finishing, all of which he had intended to release as a compilation of short meditations on diverse matters. The best indication of this urgency is the fact that the first fruits of this effort came to light well before the actual monetary essay. In effect, in 1605, only two years after the decree that mandated the re-stamping of the billon coins, and with the real consequences already plainly visible, Mariana published an early text, which already contained the heart of the argument that four years later, when published in the amplified form of a treatise, would unleash so much royal fury against his person. The opportunity that presented itself to him in 1605 was perfect. He was preparing the publication of the second edition of De rege and so he decided to insert a chapter on money just after the one dedicated to taxation. What better vehicle than a book dedicated to the education of a prince for an explanation of monetary theory? Here he could counsel against the evils caused by certain policies and try to establish the limits of political power with respect to the same issue.

Mariana began his chapter “De moneta” with an irony denoting his indignation at the policy put into action by Philip III:

Some astute and ingenious men, in order to attend to the needs that continuously overwhelm an empire, above all when it is far-flung, came up with the idea, as a useful way to overcome difficulties, of subtracting from money a certain part of its weight, such that, even if the resultant money were adulterated, it would nevertheless maintain its previous value.

Next, he explained what is concealed by these policies:

As an amount is taken from the money in terms of its weight or quality, a similar amount redounds to the benefit of the prince who mints it, which would be astonishing if it could be done without injury to his subjects.

Finally, he insinuated his own views and took the first steps toward more categorical denunciations, making it patently clear that he is referring to the King’s current policy:

In truth it would be a marvelous art, and not a secret magic but, rather, a public and laudable one, by which means great quantities of gold and silver would be accumulated in the treasury without having need to impose new tributes on the citizens. I always viewed as petulant men those who tried to transform metals, by means of certain occult skills, and make silver out of copper and gold out of silver through some chemical distillation. Now I see that these metals can change their value with no effort and no need of burners, and even multiply it, by means of a princely edict, as if by some sacred contact they were given a superior quality. The subjects will still partake of the common wealth just as much as they possessed before, and the remainder would fall to the benefit of the prince for him to apply toward the public good. Who among us has such a corrupt, or perhaps perspicacious, mindset that he would not approve of this blessing on the state? Above all if he reflects that it is nothing new. (Mariana, 1599c, pp. 339–340)

Mariana continued his exposition by presenting various historical examples of monetary manipulation, but he clarified that the fact that such policies have been carried out in the past does not justify them now. What is more, he concluded: “Under the appearance of great utility and convenience can hide a deception that produces many and worse damages both public and private, and so recourse should not be made to this extreme measure except at the experience of great duress” (p. 341).

After this thunderous introduction, our author established the foundations of his thesis and signaled private property as the principal pillar sustaining his theoretical structure. For Mariana, the point of departure is the fact that “the prince does not have any right over the private property and estates of his subjects that would allow him to take them for himself or transfer them to others,” and he affirmed that those who argue otherwise “are charlatans and flatterers, who much abound in the palaces of princes” (p. 341). Mariana maintained that taxation robs the people of their property and impoverishes them. Just in case it has not been made clear, and taking advantage of the fact that this is the very same book in which he expounds his version of the generally accepted theory of tyrannicide, he explained that to establish new taxes without the formal consent of the people makes the king a tyrant. Then he generated a parallel between inflation and taxes, argued that through the adulteration of money the king keeps for himself a part of the property of his subjects, and concluded that the king cannot devalue money without the consent of the governed.

Next, Mariana addressed the difference between intrinsic value and extrinsic value, arguing that he who would allow this difference between them to exist is a fool. The reason for this, he explained, is as follows: “Men are guided by the common value that is born out of the quality of a thing in conjunction with its abundance or scarcity, and all efforts are in vain when aimed at altering these fundamentals of commerce” (p. 343). To put it another way, men act according to their subjective evaluation of things, which is based on the properties of goods and their relative availability. He added that it is futile for the king to go against natural law and the monarch only has the right to a small commission for the minting of money.

Mariana went even further: he set out a range of natural economic laws and exposed the fraud involved in inflationary policy, which consists of altering the weights and measures of money and which he equates with robbery. Following Aristotle, he explained the origin of money and then turned against the principal argument in favor of inflation, namely, that since money has no other use than to provide necessary goods, what is wrong with the prince extracting his share and mandating that the remainder continue to circulate among his subjects with the same face value that it had previous to its devaluation? The answer is immediate: this policy is like robbery, because it destroys the wealth of the citizenry; and it is difficult to restrict because the king has greater control over the production of money than he has over the production of other goods. Moreover, according to the Jesuit, this policy has three obvious consequences. The first is that it will cause shortages and reduce the purchasing power of the people. He adds that the typical remedy on the part of the governing classes is to establish price controls, but that this solution only escalates the evil that it pretends to fix. Second, the debased money debilitates commerce. Price controls do not solve this problem either, because nobody will want to sell at the fixed prices and this will bring about runs on goods, stagnation, and the collapse of commerce. Third, upon the economic collapse, the taxes that the king continues to collect will provoke resentment.

Mariana concluded this new and valiant chapter by saying that he had performed his discussion of inflation in order “to admonish princes against altering those things which are the very foundations of commerce, that is, weights, measures, and currency, if they desire to have a tranquil and stable state, because under the appearance of momentary utility lies untold fraud and harm” (p. 351).

In sum, the daring Jesuit was telling the King that he should not let himself be carried away by those who were telling him that an inflationary policy was an easy solution to the problems of the public treasury, one which he had a right to employ. He explained that this is essentially a matter of property rights and that, if the King cannot make off with the goods of his vassals, neither can he alter the weights and measures of money. Inflationary policy impoverishes the people and hurts commerce, and the benefits of said policy are only superficial.

Mariana must have been conscious that many would consider his stance radical, and yet he was set on influencing the monetary policy of Philip III. For this reason it does not seem to be a coincidence that the second edition of De rege et regis institutione, in which he presented for the first time his anti-inflationary argument, was published together in a single volume with De ponderibus et mensuris, as if he had wished to add a long appendix expounding in detail on the technical foundations of the evil he was denouncing.

Meanwhile, the fiscal situation of the State continued to deteriorate and the monetary games of the King and the Duke of Lerma, the same games Mariana denounced in the chapter recently added to De rege, were ineffective in avoiding a new suspension of payments by the Treasury on November 7, 1607, only a few months after the conclusion of the re-stamping process begun in 1602. By then the Jesuit was already anticipating the publication of his treatise on the adulteration of money. Towards the end of the previous year he had finished writing the seven essays that would make up his new book, in which De monetae mutatione was the fourth. While the sage priest was awaiting the publication of the Latin version of the essay, he set about translating it into Spanish, once again confirming the priority that he always gave to the battle over money, which was now beginning to spill over into the intellectual world. What he surely did not anticipate was that his enemies would retreat from the public dialogue, instead leveraging political power and physical force against him with the goal of silencing his inconvenient ideas.

Around the middle of 1609 the treatise on the manipulation of money was finally published at Cologne as part of Septem tractatus, and on August 28 the King received a letter signed by one Fernando Acevedo, in which he denounced the work. The mixture of emotions that Mariana felt on September 8, when the group of armed men following the orders of Francisco de Sosa seized him and escorted him to Madrid, must have been particularly bitter. After seventy-three years dedicated to studying, teaching, certifying, and disseminating scientific ideas, the monarch responded to his independent quest for the truth in all of this work by taking away his liberty. After giving of himself to society for the better half of a century, the Government chose to persecute him, accusing him of lèse-majesté and confining him to the Basílica de San Francisco el Grande. The anger that his detailed defense of tyrannicide had failed to unleash suddenly came crashing down on him at his explication of the effects of monetary manipulation. His exposition on the causes and consequences of the inflationary phenomenon seemed more menacing to the King than the actual threat of death should he become a tyrant by not respecting the rights of his subjects.

The basic arguments of De monetae mutatione would turn out to be the same ones he had already used in his chapter on money, except that between 1605 and 1606 he had taken time to add to his historical examples, flesh out his juridical arguments, and develop his economic explications of the causes and effects of the evil that was so clearly afflicting the populace. In the prologue, in case it was not clear enough through a simple reading of the text, he underscored that the issue of monetary policy respecting billon coins was among the most important facing Spain at the time and it was what had motivated him to pen the present work. Furthermore, he implored the King to read carefully the arguments that he was going to present before condemning him for his indiscretion or deciding on whether or not he was correct. Our author made use of these initial pages to explain that the current “disorders and abuses” in the production of billon coins were making the entire populace cry out, and given that nobody dared to denounce the situation, he was taking it upon himself to do so. He even added that after so many books in which he had tried to serve His Majesty, he could think of no greater reciprocation on the part of the King and his ministers and advisors than that they should read with attention this treatise in which he had perhaps displayed an excess of missionary zeal in the denunciation of the abuses that had brought about the chaos affecting the entire country.

At the age of seventy-three, Mariana showed himself determined to rail against what he considered an injustice with grave consequences for the entire nation. He was conscious that he was inserting himself into a matter that might cause more than a few sparks to fly. Nevertheless, as he stated in another of the treatises published alongside De monetae mutatione: “the violence committed up to now will have terrorized many; but not me, for whom it only serves as a call to battle. I have proposed to establish peace between the combatants, and I am going to attempt to do so, no matter what dangers I face. It is in the most brutal and scabrous issues that one must exercise the pen.” Thus he began his treatise on money, exercising the pen in the most brutal business of them all, one that would come to be the work’s central question: Whether or not the king is the owner of the property of his subjects. For the Thomist thinker who taught at the Sorbonne, the answer was already clearly in the negative. For the septuagenarian who had developed a profound skepticism for statist solutions and a strong sympathy for the principles of individual liberty and private property, the answer could not be put more roundly, “No!” In the second edition of De rege he had already stated the case in black and white terms. The policy of continually altering the weights, values, and stamps of money, which today we would call inflationary, is a form of robbery, and he was not about to watch the same abuse take place again without decrying it.

This is how Mariana assumed for himself the voice of the people, putting the right to private property at the axis of his anti-inflationary diatribe. Having defined the core problem, he explained that the king neither has the right to establish taxes without the consent of those who will pay them nor to create monopolies, for “either way the prince appropriates part of the wealth of his vassals” (Mariana, 1861, p. 38). More still: if this is indeed the case, then “the king cannot reduce the value of money by changing its weight or its face value without the consent of the people,” and he concludes:

If the prince is not the master but, rather, the administrator of the private possessions of his subjects, then he is not allowed to take away arbitrarily any part of their possessions for this or any other reason, as occurs whenever money is debased, for then what is declared to be worth more is worth less. And if the prince is not empowered to levy taxes on unwilling subjects and cannot set up monopolies over merchandise, then neither is he empowered to make fresh profit by debasing money, because this tactic aims at the same thing, namely, robbing the people of their wealth, no matter how much it is disguised as granting more legal value to a metal than it naturally has. All of this is smoke and mirrors, and it is all doomed to the same outcome, which will be seen with more clarity in what follows. (p. 40)

Mariana then dedicated the fourth chapter of the essay to explaining the importance of being able to count on a stable currency free from manipulations. His message was clear: political alterations of money bring about price inflation. In the author’s words, the reason for this is that “if money undershoots its legal value, all merchandise irremediably rises in price to the same degree that the value of the money drops, and all accounts are adjusted accordingly” (p. 46). Besides elevating prices, the adulteration of money alters and damages the proper functioning of commerce, because weights and measures are the foundation of all exchange. What is more, monetary interventionism is typically presented as the solution to this and other problems, and yet the sage Talaveran explained that these are “like giving drink to a sick man at the wrong time, which at first refreshes him, but in the end only makes his condition worse and increases his suffering” (p. 48). Here we have Mariana presenting an early version of the analogy between the inflationary solution and the drink used to revive an alcoholic, one which Friedrich Hayek would use roughly five centuries later.

Having analyzed the matter in depth, the philosopher detailed the disastrous effects of monetary manipulation, which, as he explained, goes against all rule, custom, reason, and natural law. In the same way that it would not be licit and nobody would approve if “the king were to break into the granaries of his subjects and take for himself half of all the wheat, and then compensate them by authorizing them to sell the remaining half at twice its previous value” (p. 68), neither is it right that the king take away half the value of the money and then attempt to satisfy its owners by declaring that what was once worth two is now worth four. And the robbery can be even greater still when the king permits or, worse still, orders that debts can be paid with the devalued money.

If injustice is the flipside of adulterated money, the face of it is inflation. Goods “will become costlier in proportion to the debasement of the money supply” (p. 69). This effect provokes popular outrage and what typically occurs is that the ruler, now caught up in the dynamic of his own interventionism, tries to fix prices. Clearly this remedy will be even worse than the disease and, as the first modern historian of Spain does well to point out, this will inevitably bring about shortages, “because nobody will want to sell” (p. 69). And if this reasoning were not remarkable enough, what followed was a compounded explication of the rise in prices in conjunction with the loss of the money’s purchasing power, the one quantitative and the other qualitative. The first phenomenon responded to the fact that, as in the case of any good, the rise in the quantity of money will diminish its value. The second, though, responded to the fact that if the quality of the money deteriorates, then people will want to exchange their goods for money only if there is an increase in the amount of money being offered for those same goods.

As Mariana had explained previously, the ruler, far from reversing course, typically ventures further down his destructive path and now attends to the symptoms, instead of the causes that he himself unleashed. Thus, the fixing of prices, as an attempt to preserve the loss of a money’s purchasing power, distorts the economy even further, bringing about general privation. In other words, shortages are not accidental but, rather, the logical consequence of fixing prices. And sooner or later, the king will be forced to acknowledge the source of the problem by lowering the official value of the money back to its intrinsic value (p. 71). The end result of all of this degradation cannot be anything other than a swelling of “collective rage,” which the prince has only brought upon himself.

If we limit ourselves to material reality, there is no doubt that the king will benefit over the short term from this kind of policy, but over the long term the dynamic effects of the strategy will have forced him to worsen his own situation, via debasement of the money and its subsequent effect on commerce (and the productivity of the nation), always as delicate as milk, “which at the slightest disturbance separates and curdles” (p. 78).

But there is more. Bad money, in this case billon, exiles good money, in this case silver. Mariana described the Spanish experience as a textbook case of Gresham’s Law. This law, popularized via the formula “bad money drives out good money,” was proclaimed in 1558 by Sir Thomas Gresham. First articulated by Nicholas Oresme, it explains the effects caused by maintaining an artificial exchange rate between two currencies despite the one being devalued and the other not. Our Jesuit describes the phenomenon just as it was taking place between the new billon coins and the old ones, and he simultaneously denounces that in such situations the king should benefit by ordering that he be paid with money containing silver, precisely while he continues to make his bond payments and dole out salaries with money containing only copper. Finally, as Mariana does well to indicate, foreign creditors and suppliers will not accept this arrangement, and thus silver will flow in their direction (Mariana, 1861, p. 64).

For a man who has dedicated his life to reflecting on moral, political and philosophical problems, at both empirical and abstract levels, for a man who has lived abroad, written the history of Spain, and tried to assist in the education of the Prince, and for a man who has looked hard at the rights that predate the royal institution and even society itself, it is impossible not to see that the manipulation of money, with all of its attendant problems, is first and foremost a means of financing the public debt. Perhaps this is why the last chapter of his treatise is dedicated to the analysis of alternative measures that might resolve the Treasury’s problem without having to make recourse to the destabilizing and destructive “fraud” of debasing the money supply.

According to Mariana, instead of focusing on raising revenues as the way to solve the fiscal imbalance, the first thing that the King and those who govern ought to do is reduce expenditures. His second recommendation is to end subsidies, rewards, pensions, and prizes. This is because—and let us not forget—the King is administering resources that are for the most part not his own. Mariana does not hesitate to put the case simply, so that it will be understood:

Let us look at the matter clearly: If I were to send a representative to Rome and give him money for his expenses, would it be permissible for him to waste it and to give it to whomever he pleased, or for him to go about doling out another’s money in a public display of generosity? The king cannot allocate public money given to him by the citizenry with the same freedom with which a private individual spends the income derived from his own lands and other possessions. (p. 91)

Furthermore, he proposed that “unnecessary ventures and wars be avoided, that incurable cancerous limbs be amputated” (p. 91). In other words, those wars which are not absolutely necessary should cease and there should be no hesitation in allowing Flanders to secede from the Empire. Moreover, he suggested that the King dedicate more energy to keeping outlays in line with revenues, with the purpose of avoiding influence peddling and corruption. Finally, if it becomes necessary to raise taxes, Mariana proposed that these be levied on luxury items, which are purchased principally by the upper classes.

As a final point, he concluded once again that what needs to be avoided at all cost is inflationary monetary policy, because it runs contrary to both ethics and economic efficiency. For if such policy is pursued without the consent of the people, from whom part of their wealth is extracted through the encumbrance, then it is “illicit and wrong,” and even if it be done with their consent, he considered it a mistake and destructive for a variety of reasons.

Mariana was conscious of putting himself at risk by speaking so frankly and loudly, and he indicated as much in the prologue to the reader of De monetae mutatione: “I see very well that some will consider me too bold, others rash, saying that I do not consider the risk that I run. Nevertheless, I dare to speak out, an odd and retired man, against that of which so many wiser and experienced men than me have approved” (Mariana, 1861, p. 27). Even so, it must have been difficult for him to have imagined that the King and the Duke of Lerma would have unleashed their fury in such a virulent and immediate manner. He must have been thinking in such terms when they seized him at the chapter house in Toledo on September 8, 1609, by order of the Bishop of the Canary Islands. As he was being conducted from Toledo to San Francisco el Grande in Madrid, he would have had time to conjecture about what they were accusing him of and what would be his principal lines of defense.

Mariana was already seventy-three years old, but it was still not too late for him to learn one of the bitterest lessons of his life: if one is disposed to confront political authority in defense of individual liberty and private property, one should anticipate the likelihood that he will be abandoned by his friends and even by the institutions that he has served his entire life. This was the case, for example, with the Company of Jesus, to which Mariana had dedicated with talent and zeal his last fifty-five years. From the outset of the proceedings, the directors of the order were careful not to defend him if doing so meant compromising their interests.

The King and Lerma had been quick to detain the aged philosopher, but they would take their sweet time presenting their formal indictment. The original claim was presented by Don Fernando Acevedo on August 28. So the King waited seven days before having the Inquisition formally depose the inconvenient author and eleven more before ordering his arrest and transfer to Madrid. Nevertheless, the formal accusation would not arrive until October 27. It consisted of the following thirteen charges:

1. Denying the right of the King to reform the money supply, using formulations with which he tries to discredit and reprove the monetary policy of His Majesty, such as offending ministers and defaming the nation and its customs.

2. Omitting the reasons that justify the reform and using an erroneous methodology, thus making his work more a matter of libel than scientific study.

3. Trying to provoke and disturb the populace. In other words, trying to foment social unrest.

4. Defaming Court administrators, arguing that they are inept and given to bribery.

5. Maintaining that inflation is a hidden form of taxation, that the King cannot impose taxes without consent, and calling him a tyrant.

6. Not considering information pertaining to the troubles of the State but, rather, inciting them by labeling as “fraudulent infamy” practices similar to those carried out in other countries.

7. Classifying as inept and insolent the decisions made by ministers in the development of the national monetary policy.

8. Accusing ministers of obstruction.

9. Affirming that the nation is poorly governed, because public officials are corrupt.

10. Insisting on the “wicked and imprudent doctrine” which claims that in matters that concern all, all may express their opinions.

11. Comparing the Spanish Empire to the Roman Empire in its decadence and making fearful prognostications, in which are interwoven species of lèse-majesté.

12. Accusing the King of ingratitude toward García de Loaysa, Pedro Portacerrero, and Rodrigo Vázquez.

13. Finally, affirming that at that time and in that realm there coexisted the following grave evils: theft and deception among citizens; lack of honor among magistrates; robbery of public money; continuous imposition of new taxes, which end up paying for private expenditures or superficial expenditures of the Royal House, whereas the commoners cry out, oppressed by the great burden, and “pass their lives in anguish and pain no less brutal than death itself”; the existence of a great “number of poor who, without any hope and without having anything of their own, go about lashed to a stake”; the adulteration of the money supply with the harm this supposes to commerce and the shortage of all kinds of goods. (Fernández de la Mora, 1993, pp. 68–77)

At last Mariana knew the charges against which he would have to defend himself. As soon as the accusations were put before him, he requested several days to prepare his defense, which he decided to undertake personally. The final words of the prosecutor invited him to disavow the written record he had left in his book. How should he confront the situation? The alternatives were clear: either he renounced his principles and declared that he had made an error in judgment, or else he threw himself into defending his ideas at the risk of never being able to convince the tribunal that it was not true that he had committed “capital offenses,” as the prosecutor had claimed. On November 3 his choice was made clear via the thirty-five handwritten folios of exoneration that he introduced, which consisted of a series of formal arguments maintaining: that the publication of his work complied with the law from the moment it was granted the required license to be published; that in no way did it transgress the articles of his faith; and that it was “clear doctrine” that facts which are already public can be restated and that the majority of these had already been judged, referring to the abuses and corruptions that he denounced in the treatise. In addition, Mariana put forth four general arguments: 1) that he was being accused of supposed intentions that only God and he could know and which he had already disclosed in the prologue to the book; 2) that technically his book cannot be considered a defamatory libel because there is nothing surreptitious about it; 3) that it only mentions cases of corruption already punished as such; and 4) that it was printed in Cologne only because the domestic presses had been closed by royal decree and that he had obtained permission for its printing there.

Mounting his defense against the specific charges brought against him by the prosecutor, Father Mariana answered them one at a time with a combination of solid theological arguments and deft political maneuvering. To the first accusation he responded that he maintains his opinion that the King has no right to debase the currency without the consent of the people, for the same reasons that he had expounded in his book. To the second, he responded that he never omitted any justification for the monetary reform but, rather, that he continued to believe there is insufficient justification. To the accusation of fomenting unrest, he answered that the existence of corruption does not mean that the King knows of it and consents to it, and that he only reiterated an already public outcry. He refused to disown his affirmation with respect to the fifth accusation, according to which inflation is a tax for which the King has not obtained consent, which is therefore not legitimate, and which casts the monarch in the role of tyrant. Regarding the sixth allegation, he defended himself saying that he did not intend to incite unrest but, rather, to alert the King as to what might happen to him and what, in point of fact, has happened in other countries. Next, Mariana contested the seventh, eighth and ninth charges with a sly prestidigitation by which he tried to maintain that he was not referring to the ministers of Spain but, rather, to certain personages already condemned and to ministers in general who would establish these policies independent of consultation. He also defended himself against the incrimination that he called ministers inept and labeled their decisions insolent by alleging that “inept” means purposeless and that an “insolent” decision is merely an “extraordinary” decision, availing himself of one of the meanings that the adjective still held at the time. He responded to the tenth charge with an ardent declaration in defense of freedom of expression. Regarding the eleventh, he said that he had made the comparison between the two empires in order to warn about where we could all end up if the issue is not resolved. He accused the prosecutor of twisting his words in the twelfth accusation and, finally, he said that, regarding the final charge, he was merely referring to the public treasuries of all countries everywhere.

After reading the exculpatory text, the prosecutor levied a new charge against the Jesuit: alleging that the charges of the prosecutor are false. Nevertheless, the prosecutor must not have had much confidence in his accusations, because on December 2 he asked for a delay of the trial, to which Mariana objected. When the oral arguments finally took place, the accused philosopher encountered difficulties calling his seven witnesses, one of whom even refused to appear before the court. The other six defended the courage and honor of Mariana, after demonstrating their familiarity with his work. By contrast, of the ten witnesses called by the prosecutor only two were familiar with the book, but they all nevertheless denounced Mariana, displaying absolute complicity with the powers that be. Five of these went so far as to claim that the King could do as he wished with the money supply as well as the property of his subjects. Eight of the ten stated—without having read the book—that everything the book said is false.

On the day after the Day of the Magi in 1610, Mariana received a written statement of the cause against him and he responded that he will not enter into a discussion of positive laws but, rather, only natural laws. He further added that, if the prosecutor were correct, then private property would not exist, and he requested that all of the witnesses’ testimony against him be disregarded, for they have testified without citing the book in question. So the case was set for sentencing on January 9, 1610.

The King put Mariana’s feet to the fire, trying to condemn him for lèse-majesté, and meanwhile he called for his ambassadors to buy up or take possession of all the copies of the book they could find in order to burn them. Unfortunately, the ambassadors set themselves with such zeal to the task ordered by Philip III that today it is nearly impossible to find a first edition copy of Septem tractatus. Nevertheless, in spite of all the King’s efforts at getting the Vatican to back him in his persecution of the Jesuit, he never achieved an ounce of papal cooperation by which to condemn him.

In light of the impotence of the King, Mariana was freed, without any formal conclusion to the trial. As Gonzalo Fernández de la Mora (1993) does well to point out, contrary to what is usually believed, the episode “makes manifest the fact that the Monarchy’s power was not capricious but, rather, limited not only by the ethical consciences of its affiliates, but also by judicial review” (p. 99). The result of the trial ultimately supports the view advanced by, among others, Murray Rothbard in Economic Thought before Adam Smith, according to which institutional rivalry and jurisdictional overlap limited the power of the State in a relatively effective way, while the Catholic Church continued to enjoy a certain degree of power in Europe.

Juan de Mariana managed to overcome the nightmare in which he found himself all alone. At seventy-four, he returned to Toledo and never again occupied himself with monetary issues. In the years following the trial, he lived long enough to see how those who had persecuted him with their hatred fell from the pedestals to which they had risen. He also lived long enough to see how a new generation of intellectuals would defend his work, which was also attacked in France for its defense of tyrannicide. In spite of the physical disappearance of the book in which he had most clearly articulated his monetary theory, his ideas were defended by other authors, both within and beyond the borders of Spain. And so it was that so many millions of citizens, from his generation to our own, were made the welcome beneficiaries of the valiant efforts of this exemplary man who defended private property and freedom, even under the most adverse of circumstances.

This article originally appeared in the Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 21, no. 2 (Summer 2018).