Shadi Hamid, a longtime senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Middle East Policy, is one of the most prominent Muslim public intellectuals in America. His writings on Islam and politics, especially in relation to American foreign policy, include important insights, with which I have often agreed. His latest book, The Problem of Democracy: America, the Middle East, and the Rise and Fall of an Idea, is a bit different, however. As well argued and thought-provoking as it is, I nevertheless found it profoundly disagreeable.

What does majority rule mean without securing individual human rights and freedoms? One Muslim intellectual looks to the past for a better Islamic future. But the past is not what he thinks.

By Shadi Hamid

(Oxford University Press, 2022)

Let me begin with what is agreeable: Hamid is highly critical of the decades-old American foreign policy in the Middle East, which has often supported regional dictators for the sake of narrowly defined national interests and “stability.” A private joke made by Barack Obama, which Hamid quotes, sums it up well: “All I need in the Middle East is a few smart autocrats.” This is quite an unwise strategy, as others have also criticized. Just recently, writing for the Cato Institute, Jon Hoffman rightly noted that the autocrats in question only “reinforce many of the region’s most important problems, tensions, and grievances.”

However, these autocrats (at least the pro-Western ones) often use an argument that makes some sense to Western audiences: if they lose power, Islamists will replace them, and they will be worse. The archetypal dilemma here is to be found in Egypt, Hamid’s country of origin, which looms large in his narrative, where free elections in 2012 brought the Muslim Brotherhood to power, only to be followed by a brutal military coup in 2013. Those who were worried that the Muslim Brotherhood would ultimately impose Sharia, or Islamic law, and build its own party-state either supported the coup or at least tolerated it. Consequently, a non-Islamist dictatorship, the model that had ruled Egypt since 1954, was restored.

This is the vicious cycle in the Middle East—secular-leaning autocrats versus popular Islamists—that many good-willed people want to break. I myself have written about it, seeking the solution in “nurturing liberal democracy in Muslim‐majority societies, in which both secular and Islamic forces can coexist without either of them becoming hegemonic and intolerant of the other.” But Hamid has a different suggestion: Let the Islamists come to power with elections, rule as they wish, and feel free to get rid of the “liberal” side of liberal democracy.

That is why much of Hamid’s book is a long diatribe against liberalism. But beware: What he means here is not the left-wing progressivism that the term “liberal” implies in American politics today. Instead, he means the classical liberalism that many American conservatives have traditionally cherished. It is the very foundational American idea that every human being bears inalienable rights, which Hamid all-too-neatly distinguishes from democracy:

The classical liberal tradition, emerging out of the Enlightenment after Europe exhausted itself with wars of belief, prioritizes non-negotiable personal freedoms and individual autonomy, eloquently captured in documents like the Bill of Rights. Meanwhile, democracy, while requiring some minimal protection of rights to allow for fair and meaningful competition, is more concerned with popular sovereignty, popular will, and responsiveness to the voting public.

After clarifying this distinction, Hamid throws his lot in with “democracy.” He also calls all policymakers to “privilege democracy, with its emphasis on the preferences of majorities or pluralities through regular elections and the rotation of power, over liberalism, which prioritizes individual freedoms, personal autonomy, and social progressivism.”

Hamid’s reference here to “social progressivism” may conflict with what I just wrote above: By “liberalism,” he means classical liberalism, which is in fact distinct from “social progressivism.” (It could even go against it.) Yet throughout his book, Hamid often conflates the two, making his “liberalism” a bit too vague.

But perhaps there is a good reason for that: As Hamid has put it elsewhere, he agrees with America’s “post-liberals, including the national conservatives,” that it is inherent in classical liberalism ultimately to “discard traditional conceptions of gender and sexuality and [turn] aside the views of anyone who objects.” In other words, he agrees with neo-integralist scholars such as Patrick Deneen who argue that American classical liberalism is intrinsically hostile to Christianity—and, of course, Islam, too.

Inescapable Universal Rights

Theoretically, the most interesting—and to me the most unacceptable—part of Hamid’s argument is his dismissal of the very concept of universal rights. “Rights are not,” he asserts, “freestanding, self-evident, or morally transcendent.” Therefore, rights cannot be held above any democracy. Instead, “rights would be derived from the democracy.” This inevitably means that majorities should rule as they wish, without being constrained by “individual freedoms and minority rights.” A classical liberal, however, would insist that there are, in fact, universal rights, which are rooted in natural law. But Hamid seems uninterested in that argument. The term “natural law” does not even appear in the book.

There is a key flaw in Hamid’s argument against universality, however: It cuts down the branch on which he is sitting. For if there are no universal rights, such as freedom of speech and religion, why should there be an absolute right to vote? If his dismissal of liberalism is valid—that it is a subjective Western system that other civilizations don’t need—why is the same dismissal not valid for democracy as well? In fact, that is exactly what pro-regime ideologues in Beijing and Moscow, and pro-ruler clerics in Riyadh and Dubai, argue.

Hamid seems to push this theoretical argument mainly to substantiate the legitimacy of democratically elected Islamists in the Middle East. I can see how it will be music to the ears of those Islamists, as well as many conservative Muslims who may be uninterested in the rights of secular individuals or non-Muslims in their midst, let alone the rights of those branded as “heretics” or “apostates.”

But these Muslims deserve to be cautioned: Hamid’s argument cuts both ways. In other words, it also means that in contexts where Muslims are minorities, their rights can be curbed as well, this time by non-Muslim majorities. I confirmed this with Hamid on a lively panel about his book sponsored by the Center for the Study of Islam and Democracy. I asked him whether, in his worldview, it is legitimate for French secularists to ban Islamic veils of Muslim women or for India’s Hindu supremacists to punish Muslims for eating beef? His answer was that he would not favor such bans, but, yes, it would be legitimate.

How Far Is Too Far?

How far could such illiberal democracies go? In much of his book, Hamid focuses on the Middle East, especially the ambitions of Islamists, arguing that they can’t, in fact, go too far. Yes, Islamist parties ultimately want tatbiq al-shariah, or “the application of Sharia,” he writes, but “they have struggled to define what it is exactly that they want.” When they come to power, there will be some “Islamization,” he admits, like alcohol bans or limitations on women’s sporting events, but all that is tolerable, as even non-Islamists in the Arab world are socially conversative. One wonders about more burning issues such as capital punishment for “apostasy” and “blasphemy,” but the book offers no answers.

If there are no universal rights, such as freedom of speech and religion, why should there be an absolute right to vote?

In fact, there is a country where we can see how “application of Sharia” and “Islamization” has taken place in the context of an electoral democracy: Pakistan, which gets praised by Hamid, along with Malaysia, for being, despite “flaws,” “considerably more democratic than their Arab counterparts.” That is all that we hear about Pakistan. Any observer of this Islamic Republic, however, could see how its “Islamization,” which took place in the 1970s and ’80s under a military regime but also with “popular demand,” led to horrific results for women as well as religious minorities such as Ahmadis, Shiites, and Christians. Speaking out of that experience, Pakistan’s former ambassador to the United States Husain Haqqani cautions us that, for mainstream Islamists, democracy is just a tool to come to power and what they “actually seek is a dictatorship of the pious.”

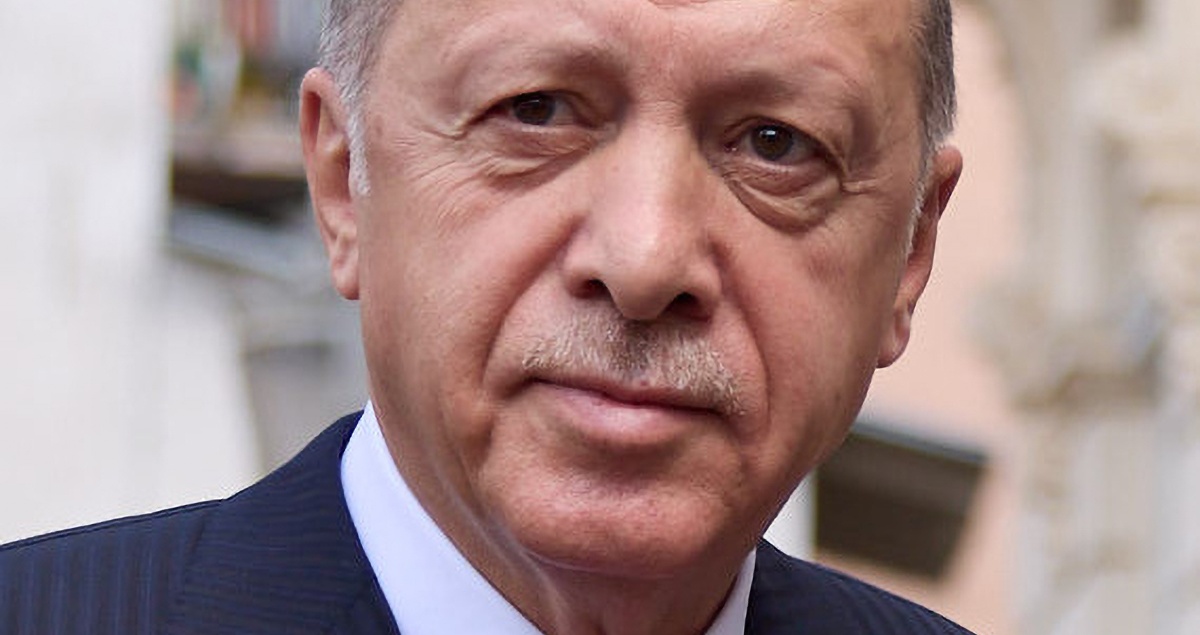

There is another country relevant to this discussion—my native Turkey, which Hamid discusses. He says that, in the past two decades, under the democratically elected president Tayyip Erdogan and his AK Party—Islamists by Turkish standards—Turkey has seen only a “soft Islamization.” That is true, but speaking out of my experience, there is something Hamid overlooks: Turkey’s ruling Islamists don’t want to “Islamize” their secular compatriots: They just want to make them—along with the “traitors” from their own ranks—suffer. They also want to “conquer” everything that the seculars used to own—from media, universities, and businesses to the entire state itself, down to even the neighborhoods. It is another exercise in “the dictatorship of the pious,” whose endgame remains to be seen.

Without liberty, democracy easily collapses into the tyranny of the majority.

Granted, one can say that Turkey’s seculars have not been too humane either, which is true also for most non-Islamist forces in the Arab world. And that is the fundamental problem: The region is tormented by endless conflicts between vicious tribes—political, religious, and ethnic. In a passage with which I agree, Hamid notes this fact:

In this book, there is no “resolution” to the problem of religion and politics. The problem of deep difference over the role of Islam will remain, with neither side able to conclusively defeat the other. There will be Islamists and there will be secularists, with many shades in between.

Shrink the State

I can offer a resolution to this problem: Minimize the state and maximize the freedom. Minimize the state so there are fewer public resources for these irreconcilable tribes to fight over. Maximize the freedom so the Islamists can live by their Sharia but not impose it as the law of the land, while others live as they choose. (Similar to Israel’s accommodation of all sorts of Jews, from the ultra-Orthodox, who live by their Halakha, to the atheists.) Also, boost free market capitalism so that economic rationality thaws strict communal boundaries and empowers individuals. In other words, support both political and economic liberalism.

Hamid could argue that this is perhaps a nice liberal dream but not realistic. Liberalism, he says, “can’t but clash with Islam.” Islamic reformers can try to change things, but they have little chance: “This is not Islam as it ‘should’ be, but Islam as it has been—nearly uninterrupted for the better part of fourteen centuries.”

Yet this argument, too, has an ironic blind spot: for some 13 centuries, “Islam as it has been” did not include democracy, Hamid’s favorite political system, either. Medieval Islamic political doctrine never advocated free elections, political parties, parliaments, and term limits. Such ideas appeared in the Islamic civilization only in the 19th century, with Western influence, and thanks to thinkers such as the New Ottomans. They are often called “Islamic liberals,” as they advocated not just political representation but all the key features of political and economic liberalism as well, finding inspiration from the Qur’an and the Prophet’s example. (I myself am an admirer of such pioneers in this regard as Namik Kemal and Khayr al-Din al-Tunisi, as I highlighted them in my book Why, as a Muslim, I Defend Liberty.

So if Muslims had stuck simply to “Islam as it has been” and never advocated new ideas, democracy would also not have occurred to them. Similarly, “Islam as it has been” included slavery until the 19th or even 20th century—when it was abolished thanks to international human rights campaigns from outside, as well as efforts of Islamic and secular liberals from within.

That convinces me that “Islam as it has been” can change even more—toward liberty. And I find that absolutely necessary, for without liberty, democracy easily collapses into the tyranny of the majority. But I also believe that the people of the Middle East, and people elsewhere from East to West, deserve better than that. They deserve the dignity of liberty.