It was not my idea to review a book on the history of Christian rock music, but in a few respects I do have some bona fides. For a couple of decades now, I have been a confessional Lutheran, a member of a church body that boasts a rich historical musical tradition that includes the works of J.S. Bach, and I have even been at a Catholic church liturgy where, rather than Gregorian or polyphic chant, they sang Luther’s reformation anthem, “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” My knowledge here isn’t especially scholarly, but I do know a thing or two about traditional Christian music.

Contemporary Christian Music has both fans and detractors, but a new book examining its roots and cultural/spiritual impact says more about the author’s politics than it does about the power of praise choruses.

By Leah Payne

(Oxford University Press, 2024)

Additionally, I joined my first rock band when I was 15. This was in the early ’90s, when I was in high school in the Pacific Northwest at the height of grunge, and I played in bands off and on for the next 15 years. My modest pinnacles of success include opening for a band that went on to sell 40 million records and being in another that had a top 10 hit in the Dominican Republic. I currently have something of an avocation as a music critic, so I guess I also know something about rock music.

To the extent that this makes me qualified to opine on Leah Payne’s God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music, my baseline professional assessment of the genre was that of beloved television sage Hank Hill: “You’re not making Christianity any better. You’re just making rock and roll worse.”

However, despite a passing familiarity with some of the bigger Christian Contemporary Music (CCM) acts of the past 40 years, I did not grow up with much exposure to the Christian rock scene. I was genuinely looking forward to learning more about it, as well as having my opinions challenged and horizons expanded. And in the former respect, God Gave Rock and Roll to You does the job. If you need a rote recounting of the rise of Christian pop music dating back to the late 19th century, including notable people and performers, chronologies, minor controversies, and the development of the businesses that sustain this niche marketplace, well, that’s all here.

Beyond that, Payne, a professor of religious history at Portland Seminary, at least sets the expectations early on by informing readers she was the daughter of a Pentecostal pastor and was subjected to a decent amount of CCM in her youth. She then spends much of the book taking out her rejection of the culture she was raised in on the rest of us. And it’s all done with a healthy dose of overtly liberal politics and academese:

As I studied American religion, however, my perspective on CCM began to change. I began to regard Contemporary Christian Music performances as more than quirky evangelical entertainment. Instead, I came to see CCM concerts as sites where power is created and negotiated. At CCM performances, entertainers exerted influence over attendees by soliciting public conversions, stoking political action, and seeking donations for social causes. In these performances, bestselling CCM stars and their audiences also performed and enforced strict evangelical ideals about gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, and class.

Naturally, everything that follows reflects her feminist convictions and is unhelpfully racialized. (I am begging Payne to talk to one or two flesh-and-blood Hispanic Americans and ask them what they think of her use of the term “Latinx.”) Payne treats traditional Christian views on womanhood as some sort of recent distortion rather than rooted in the Bible, blaming “new Calvinists” such as John Piper for making “male headship and female submission a central tenet of the evangelical faith.” She also seems to think there’s an obvious throughline between the fact that the KKK used to hand out religious songbooks and that 60 years later “CCM rarely broke the so-called sonic color line, which segregated most popular music in the United States and racially coded it as Black or white.” The far simpler explanation is that, in the 1980s, when CCM came into its own commercially, the United States was still 80 percent white, and the brand of evangelicalism that gave rise to CCM was rooted in white culture, the same way rap emerged in the 1980s rooted in black culture.

That said, it’s worth noting the historical fact that gospel music was popular in the Jim Crow south; one might want to ask what that means. But it’s quite another thing to engage in inflammatory speculation that “white Southern Gospel quartets expressed a desire for what they saw as a simpler (antebellum) era. An era in which religion was not tainted by the urbanizing, technology-driven modern world, or by the confusing new social order that Black citizenship might bring.”

While Payne may claim to be professor of religious history, it seems quite obvious at times that she’s not steeped in music history beyond her subject.

Indeed, while Payne may claim to be professor of religious history, it seems quite obvious at times that she has large gaps in her knowledge of music history. On this point, Elvis is barely mentioned in the book, only popping up a few times in the second chapter. “Elvis ‘the Pelvis’ Presley credited his dancing and his vocal inflections to the ‘spiritual quartets’ and Pentecostal congregations that raised him,” she notes.

That’s understating things quite a bit. Peter Guralnick’s seminal Elvis biography, Last Train to Memphis, makes it quite clear that Elvis was obsessed with the southern gospel quartets of his era, and early on his goal was to join such a quartet. (Elvis still went on to record several spirituals over the course of his career.) At the same time, Elvis was obviously into the emerging blues, R&B, and rock music that was heavily associated with black performers and personally held very progressive views on race. If there was a tension between southern gospel music being threatened “by the confusing new social order that Black citizenship might bring” and embracing black culture, Elvis Presley, the man perhaps most responsible for defining pop music as we know it, sure didn’t think there was.

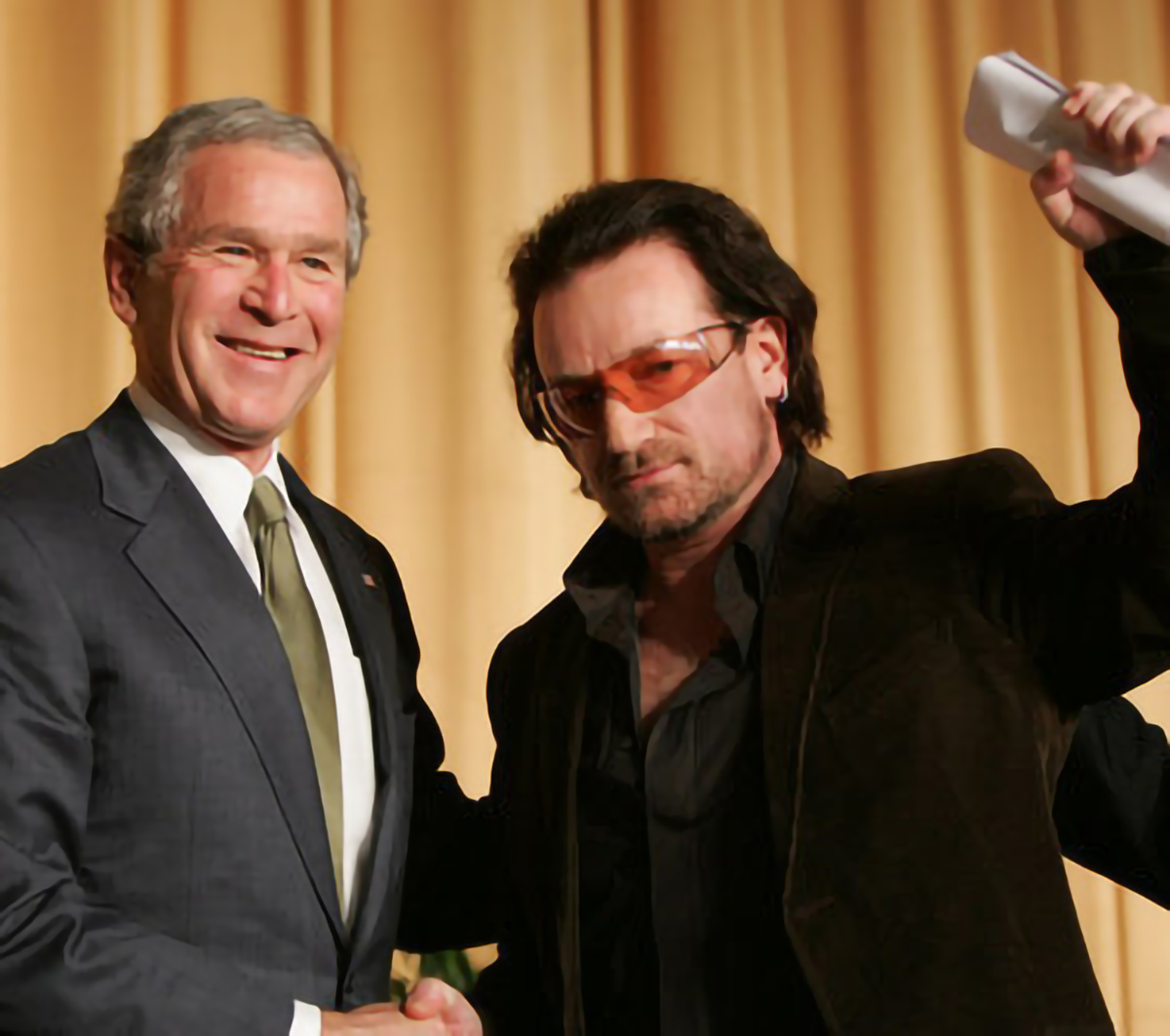

Indeed, the book generally gives short shrift to the numerous other big-name stars who found room for gospel music within their broader mainstream careers—Johnny Cash and Dolly Parton, for example, are barely mentioned. The most astonishing omission is there’s virtually no discussion of U2, except for two paragraphs near the end about how Bono courted evangelical leaders to help convince George W. Bush to address the AIDS crisis in Africa.

The revelation in the 1980s that Bono and two others in U2 were part of a Christian community and at one point considered giving up music out of commitment to their faith sent shockwaves through the music press and churches alike. To this day, the musical aesthetic of nearly every evangelical praise band, with the swelling synth pads and dotted eighth-note guitar lines, heavily borrows from U2. There’s no rock band more influential on CCM and they’re virtually absent from the book? I suspect that the discussion of these broader influences is limited so as not to undermine Payne’s contention that CCM is the primary product of a backward evangelical subculture. Acknowledging more mainstream and more politically diverse influences would complicate things quite a bit.

Further, while Payne does a good job covering the breadth of the artists within the Christian rock and CCM scenes, there’s little reflection on the artistic, rather than ethnic and gender, diversity within the movement. For example, early ’70s Christian rock pioneer Larry Norman had a shockingly blunt lyrical approach, as evidenced by his song “Why Don’t You Look into Jesus?” which was recorded by Janis Joplin:

Gonorrhea on Valentine’s Day,

And You’re still looking for the perfect lay

You think rock and roll will set you free

Honey, you’ll be deaf before you’re thirty-three

Shooting junk till you’re half insane

Broken needle in your purple vein

Why don’t you look into Jesus, He’s got the answer

Payne notes that Norman “scandalized” listeners but hardly says anything else about him, even though Norman was one of the most influential and unorthodox figures in Christian rock. There is some good discussion, however, of the tensions created when ’90s Christian acts, such as Jars of Clay and Sixpence None the Richer, crossed over into the mainstream alternative charts, as well as the anti-authoritarian attitudes of Christian punk bands on the seminal Tooth and Nail record label.

Much of this book is dedicated to portraying CCM as an industry wholly concocted by James Dobson and Billy Graham to brainwash kids into becoming conformist Republicans, yet these threads are picked up and discarded before they can introduce too much in the way of nuance and complexity. I can only conclude Payne has written a book on Christian rock far more interested in talking about evangelicals than the particulars of the music they produce.

And on that point, I’m sorry to report that Payne’s understanding of Christianity—something she ostensibly does know something about—doesn’t come off as any more nuanced. I am not simpatico with evangelicals’ approach to engaging politics and the culture, and heaven knows that if I walk into a church and see a drum riser where an altar should be, I am in the wrong place. As such, I’m superficially inclined to agree with a number of Payne’s critiques, albeit for reasons actually rooted in my Christianity, not politics of any kind.

There’s something to Payne’s point that “the story of CCM is the story of how white evangelicals looked to the marketplace for signs of God’s work in the world.” Measuring your faith in terms of commercial success and cultural influence is a form of prosperity gospel, and one certainly sees that among evangelicals in CCM who aren’t well grounded in Christian concepts such as vocation. But such theological precepts, once again, are often thrown out there by the author but never explored.

There’s no rock band more influential than U2 on CCM and they’re virtually absent from the book.

What we’re left with is a bunch of anecdotes about how the pressures of fame led many CCM stars to fail to live up to the strict moral standards expected of them. But the implicit questions readers are left with about these failures are largely focused on matters of hypocrisy and whether, say, evangelicals should rethink their attitudes about premarital sex. While there are criticisms of evangelical culture to be had here, biblical Christians would instead focus on forgiveness and our shared sinful nature, a perspective largely absent from God Gave Rock and Roll to You.

Similarly, I would also agree with Payne that there has frequently been a problem with civil religion in CCM. But it’s pretty clear that when she recites the litany of times CCM superstar Michael W. Smith has sung at a Republican convention or the work that CCM stars have done opposing abortion, her objection isn’t the mixing of religion and electoral politics per se but having political beliefs Payne herself rejects.

The last part of the book is when Payne finally lays her cards on the table with an ear-shattering crescendo of But Trump!, blaming evangelicals for enabling him. “Scholars showed that Trump’s triumph among white evangelicals—a reported 81 percent voted for him—was the logical outcome of generations of evangelicals’ embrace of militant masculinity, racism, and economic inequality,” she writes. I was too busy rolling my eyes to bother with the footnote on that allegedly empirical assertion smearing tens of millions of Americans, but suffice to say, I’m quite certain that “Scholars showed” is doing the devil’s work in that sentence. Music is almost incidental at this point, but Payne actually remonstrates a former worship leader of the popular Bethel megachurch for criticizing Black Lives Matter riots in Portland by blaming the city’s problems on “far-right activists” doing “crowd control.” A person who openly identifies as Antifa recently came close to winning a mayoral election in that city, but whatever.

While I myself might be inclined toward conservativism, I’m quite comfortable existing in progressive spaces and I don’t honestly care about Payne’s politics beyond the fact that they get in the way of the truth. I also wish Payne didn’t mirror the evangelicals she’s critiquing by routinely evaluating the worth of Christianity on a left-right political continuum. (I suspect that D.G. Hart’s insights into how Lutherans and confessional Protestants approach matters of civil religion in his books The Lost Soul of American Protestantism and From Billy Graham to Sarah Palin: Evangelicals and the Betrayal of American Conservatism would, well, rock Payne’s narrow approach to these issues.)

As it is, I hate to tell fans of Kiss and CCM alike that God Gave Rock and Roll to You is mostly a waste of a good title. Payne hasn’t made our understanding of Christian rock any better, but she has made our politics worse.