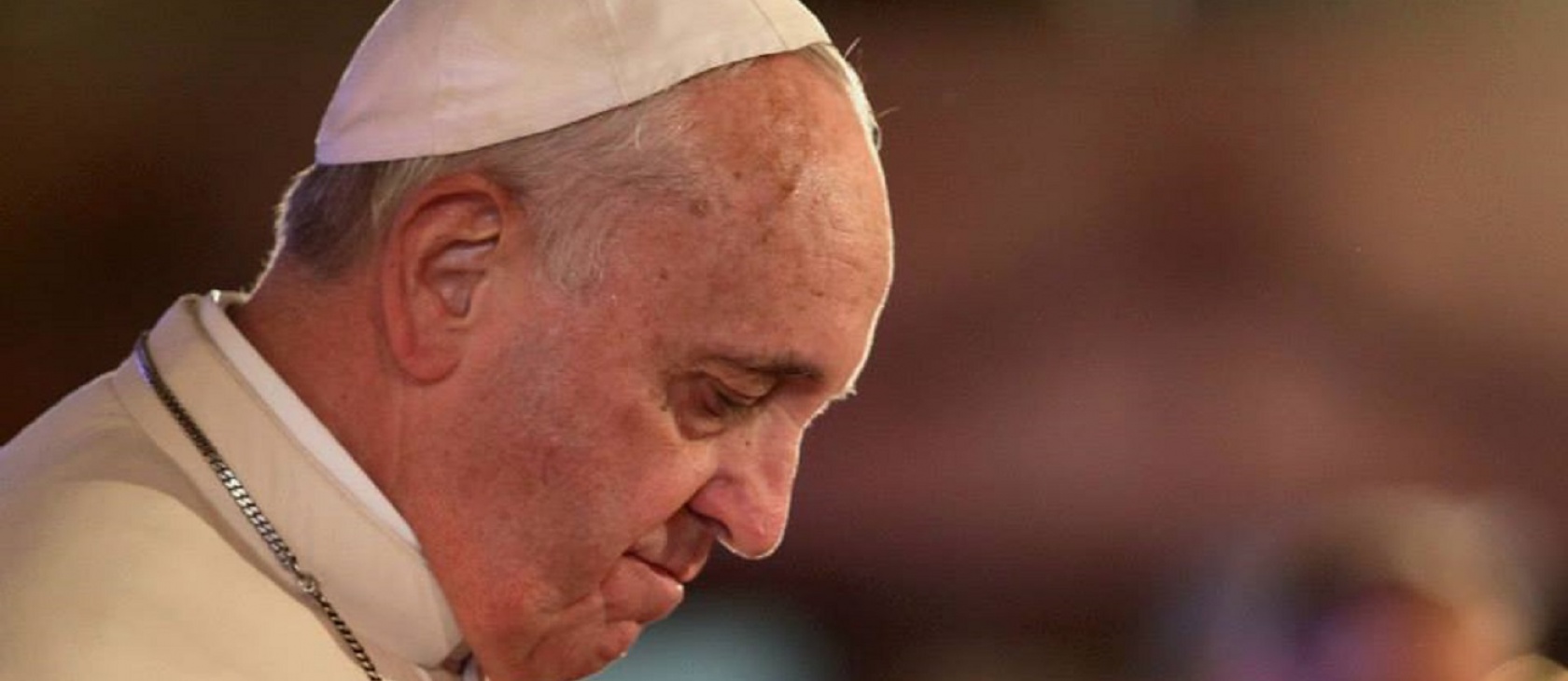

Pope Francis recently spoke to an Italian anti-usury group to condemn the practice of “usury,” calling for an end to exploitation and for more education. He spoke to both parties who might be involved in a problematic financial relationship: He wisely spoke about the importance of people living simple lives so that they did not take on unnecessary debt, and he also spoke against lending at high rates of interest. He also commented on the importance of people helping those in need through volunteer work instead of lending money – excellent pastoral advice.

But what is usury? What is the Church’s teaching on it? When is it problematic, and when is it wise, for the government to intervene in the matter?

In some traditions, usury involves any lending with the expectation of receiving interest. Thomas E. Woods, in his book The Church and the Market, examines the history and evolution of the Roman Catholic Church’s teaching. He argues that the prohibition of all interest on lending is a very difficult position to sustain as a universal principle.

Although some borrowers might need money for urgent consumption purposes (such as buying food), others may borrow to invest (for example to start a business). Surely it is unreasonable for the lender not to receive compensation in the form of interest, at least in the second case. After all, the borrower wants the capital to make some money for himself. The lender, in making a loan, is also giving up the opportunity to invest the money elsewhere and make a return, or he deferring his own consumption. Not only that, it is surely just if the lender is compensated for inflation (the decline in the purchasing power of the money he lent), for risk (the possibility that he might not be paid back), and for related expenses (setting up the transaction, checking the bona fides of the borrower, and so on).

For these reasons, the Catholic Church seems to have settled on a definition of usury that involves the charging of excessive interest. The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church points out that the quest for a reasonable profit is perfectly acceptable. In a brief discussion, it focuses on the impact of the loan on the borrower – specifically, that if usury leads to hunger and death the lender is indirectly committing murder.

Comparing the cost of a short-term loan with longer-term alternatives is like comparing the cost of renting a hotel room at a nightly rate for 365 nights with renting a house for a year.

This idea of “excessive” interest is not necessarily easy to put into operation, and its application in practice requires some ethical discernment. This is not to say that it is unimportant, but government regulation can be a sledgehammer that misses a nut. Let’s think of this from both the lender’s and borrower’s points of view.

Consider a payday loan. Such loans are typically small and are repaid over a short period of time. When their interest rates are “annualised” – calculated as if the loan were rolled over on the same terms, month after month, for a whole year – incredible rates of interest are quoted. However, it is, in fact, easy to reach a large figure for the interest rate without any substantial profit being made, simply because of the nature of the transaction.

For example, imagine a loan of £100 for two weeks, which involved an administration cost of only £5 and where this was the only cost passed on to the customer (with no allowance for interest, profit, or risk of non-repayment). The annual effective rate of interest on such a loan would be more than 250 per cent. Comparing the cost of a short-term loan with longer-term alternatives is like comparing the cost of renting a hotel room at a nightly rate for 365 nights with renting a house for a year.

You might be thinking “the fact that the lender is not making a particularly large profit from the transaction is not much comfort for the borrower – it could still lead the borrower into a spiral of debt with devastating consequences.” But this is not as clear as it seems. An individual who has a very low, predictable income and uses a payday loan to meet regular expenses is likely to run into trouble. On the other hand, if somebody whose winter electricity bill is due five days before he is to be paid takes out a payday loan and repays it within the month, he avoids either a bad credit record or the hassle (and possibly additional cost) of a bank overdraft. Students may also take out payday loans, perhaps because of the need to buy a large consumer item (such as a laptop), just before their student loan payment is made by the government. Before the market was regulated in the UK, the average payday loan borrower had a similar level of education than the average of the population and was more likely to be working.

Whether lending at high cost is exploitative, or sends the borrower into a spiral of decline, very much depends on the particular circumstances of the lender and the borrower.

What would happen if we were to regulate interest rates? We know the answer to this question, because many jurisdictions do regulate payday lending. Regulation of payday loans tends to make complete financial breakdown and subsequent difficulty obtaining housing and employment worse; leads to the use of illegal lenders, who tend to have rather brutal methods of enforcement; leads to greater reliance on family members; and leads to the use of more expensive forms of credit. (Evidence from various studies can be found in the IEA’s Flaws and Ceilings, edited by Coyne and Coyne, pp. 139-146.)

Whether lending at high cost is exploitative, or sends the borrower into a spiral of decline, very much depends on the particular circumstances of the lender and the borrower.

Perhaps Christians should reflect a little more on the Islamic perspective on usury. Here the focus is on the problems of debt contracts that involve interest. It is feared these lead to an unequal sharing of risk and, therefore, have a negative effect on personal relationships. For example, if somebody borrows money with interest to start a business and that business fails, the lender is owed a debt – and may pursue this with devastating consequences for the borrower. However, these consequences are much alleviated by the modern treatment of debt and bankruptcy, especially in the U.S. (though whether this is entirely a good thing is a moot point). Would it not be better if the lender took an equity interest in the business instead?

It might well be the case that it would be better for more providers of finance to take equity stakes instead of lending at interest. Christians could certainly learn from Muslims. However, their own difficulty is illustrated by the fact that so many Islamic finance products seem to try to get as close as possible to their Western equivalents whilst remaining compliant with Shari’a law.

What are the lessons? First, the tax system should never favour debt over equity. In most Western tax systems, equity finance is taxed at a penalizing rate. This was especially true in the U.S., until President Trump’s recent reforms redressed the balance somewhat. Secondly, we should, as Pope Francis suggested, voluntarily help the needy out of charity rather than lending money. And perhaps churches should more actively support the development of credit unions. These could provide cheap loans and develop personal relationships with the borrowers to help them better manage their affairs. In addition, moneylending companies should behave ethically – they should be careful to ensure that their practices reduce, rather than increase, their clients’ need for credit.

However, we should be wary of regulation. Some forms of regulation will have worse side effects than others. But all have the potential to make a bad situation worse and to increase the risk posed to those who are in daunting financial circumstances. Pope Francis’ remarks did not mention regulation but, instead, offered pastoral advice that was sound – and important – for individuals to heed.